mieducation

BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and Impact

This article marks the beginning of a series, edited by Dr Debarun Dutta and Neil Retallic, encapsulating the significant conclusions from the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia publications. These reports are the result of a comprehensive review by global authors, examining all aspects of presbyopia and this first article focusses on the epidemiology and impact of presbyopia.

WRITER Neil Retallic

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Be informed about new definitions of presbyopia and why standardised terminology is important,

2. Understand the extent of presbyopia globally, and

3. Understand how to identify those at increased risk of presbyopia.

Ageing is an inevitable part of life, a journey that brings with it the gift of wisdom gained from our experiences. However, societal perceptions often cast a shadow over the physical and mental transformations that accompany this natural progression.

Interestingly, the World Health Organization believes that most developed world countries characterise old age from 60 years and above, and estimates that between 2015 and 2050 the global proportion of this age group will nearly double from 12% to 22%.1 In optometric practice, part of our regular ‘bread and butter’ work includes diagnosing, communicating, and managing presbyopia, which is often one of the first ocular signs of ageing. This article highlights the key findings from the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact publication relating to the prevalence, and impact of presbyopia.2

DEFINITION OF PRESBYOPIA

Across the literature, there are various selection criteria for presbyopia, which makes prevalence comparisons challenging. Some studies rely on near vision performance alone, whereas others include a comprehensive battery of clinical tests.

The global consensus definition in the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia publications is:

“Presbyopia occurs when the physiologically normal age-related reduction in the eye’s focussing range reaches a point that, when optimally corrected for far vision, the clarity of vision at near is insufficient to satisfy an individual’s requirements.”3

The two main ways presbyopia has been classified are:

(a) Functional presbyopia, where there is reduced near vision (N8 or less, approximately 0.4 logMAR), which can be corrected to improve vision. Logically this would mean that those whose myopia handily provides good near vision uncorrected would be exempt from studies using this approach.

(b) Objective presbyopia, where distance refractive error has been fully corrected and there is near vision of N8 or less due to the associated loss of accommodation. This criterion includes all refractive errors. The definition of accommodation is the change in optical power due to the crystalline lens changing shape and position.

PREVALENCE OF PRESBYOPIA

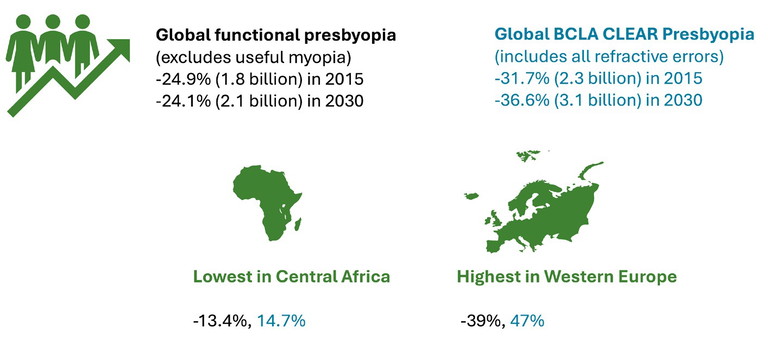

Naturally, studies using functional presbyopia assessments have reported lower overall prevalence levels. In 2015, it was estimated that around one in four people across the world (24.9%) had functional presbyopia, which equates to approximately 1.8 billion individuals.4 When considering the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia definition, this increases to nearer to one in three people (31.7%, 2.3 billion individuals).

The changing population dynamics means the prevalence may well have peaked around 2020 and by 2030 there are likely to be over two billion individuals with functional presbyopia or over three billion when applying the latter criteria (Figure 1).

NEAR EFFECTIVE REFRACTIVE ERROR COVERAGE

Near effective refractive error coverage (near eREC) represents the proportion of the population that has their near refractive correction with a good quality outcome.

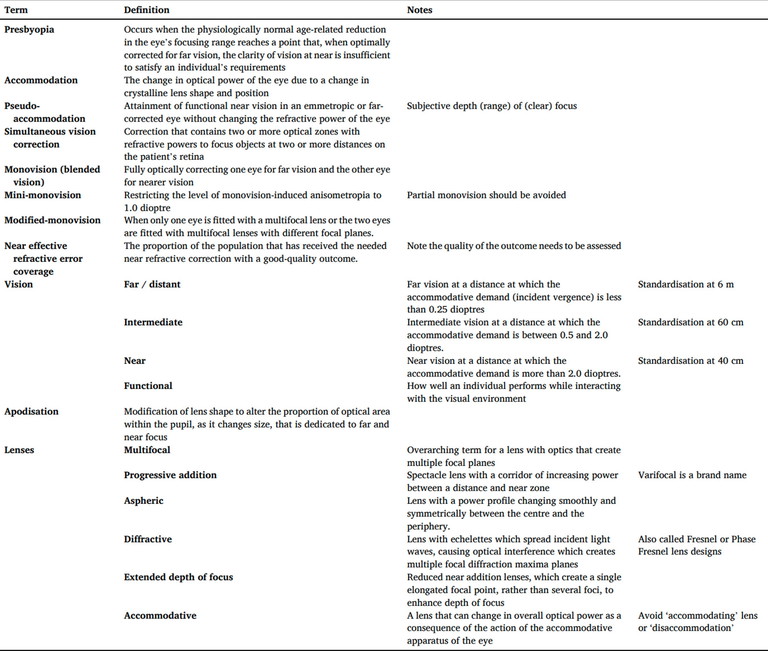

Table 1 provides a useful overview of other relevant terms associated with presbyopia.

Figure 1. Prevalence of presbyopia, colour coded per research methodology.

Table 1. Definitions of terms associated with presbyopia.

The global near eREC is around one in five adults (20.5%, for adults who are 50 years or over). This is lower than for distance eREC (42.9%),5 promoting the World Health Assembly to set a 40% increase target for near eREC by 2030.

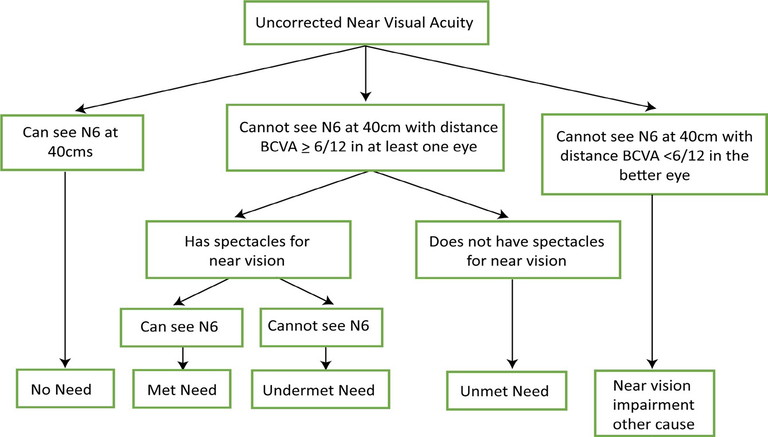

For consistency, best practice guidance for near eREC visual assessments include using Times New Roman N6 or N8 font size at 40 cm and ensuring distance vision is 6/12 or better, to exclude pathology which may be impacting visual performance. LogMAR is preferrable over Snellen acuity measurements. Figure 2 highlights the inclusion protocol.

UNCORRECTED PRESBYOPIA

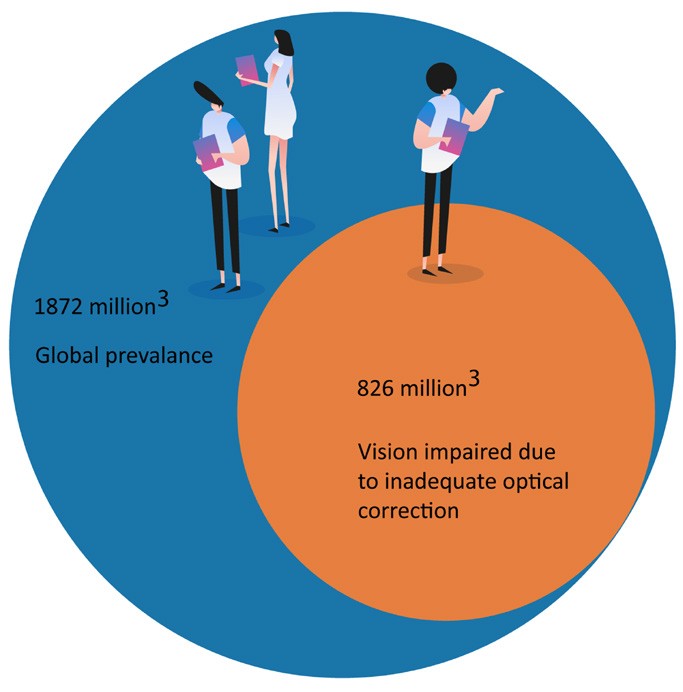

Unfortunately, too many people (1,872 million) suffer from uncorrected or suboptimal correction of presbyopia, despite the wide range of eyewear/refractive management options available. This comes with high consequences (Figure 3) with too many suffering from visual impairment (826 million) and feeling disabled.

Figure 2. Flow chart protocol for near eREC assessments, based on near acuity in the better eye.

Researchers have revealed that overall refractive error causes more vision impairment at near than in the far distance and the prevalence of uncorrected near vision may be six times larger than that for uncorrected distance vision.

RISK FACTORS FOR PRESBYOPIA

Although age is just a number, this has the highest single association to presbyopia, with the prevalence increasing with old age. Generally, you would expect patients to start presenting with issues between 40–49 years old (27.6%), although some will present younger, especially if they have multiple risk factors. Nearly all adults will experience presbyopia by 60–69 years old (81.8%). The prevalence of uncorrected presbyopia also increases with age, although there appears to be one exception in rural Japan; of interest will be what learnings can be drawn from this unique society.

Near eREC has been found to increase from around half (47.4%) among 30–49 year olds to three quarters (75.7%) in those over 70 years of age.

There are also regional differences, with the lowest prevalence levels reported in central Africa (under 15%), and the highest in Western Europe (which could be nearly 50% depending on the study methodology).

South Asia has the largest number of uncorrected presbyopes (275 million). The best location, in terms of near eREC is Los Angeles (87%) and the worse is Tripura in India (0.3%), showcasing the huge differences across the globe, which favour those in high income countries.

Figure 3. Statistics relating to uncorrected presbyopia.3

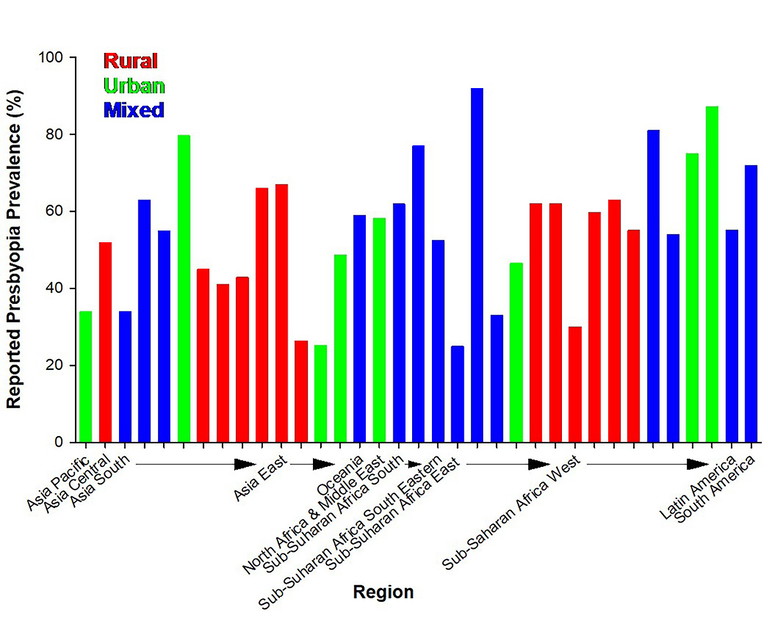

Figure 4. Presbyopia prevalence by location.

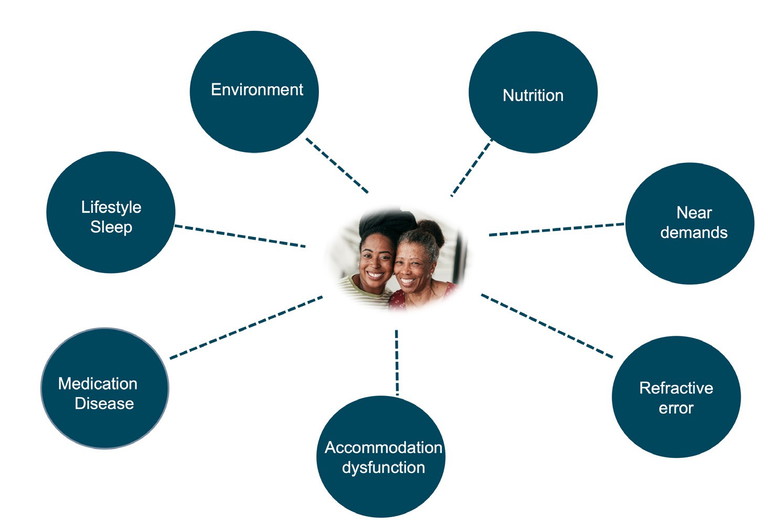

Figure 5. Risk factors for early onset of presbyopia.

Urban locations tend to have higher prevalence rates (25–80%), when compared to rural populations (36–67%), although there is a large variation (Figure 4). Some studies have suggested these differences may only be significant in countries with a low/ medium development index and therefore may be more related to differing economic conditions. Areas with high air pollutant concentrations have also been linked and may double the prevalence of presbyopia.

Women show a higher prevalence of presbyopia than men when matched to the same age group, possibly due to the typical tasks and viewing distances used. This is interesting as males generally have lower accommodation levels. The findings for near eREC are mixed when comparing males and females.

Socioeconomic status, literacy and education, health literacy, and inequality are not easy to isolate from other aspects, although are likely to be lower contributing factors to presbyopia. These associations tend to be plausible rather than proven and include refractive error, diet, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, systemic disease, and type of work. Equally there may be conflicting outcomes, for example an office-based worker in a higher socioeconomic setting may minimise their exposure to UV/air pollutants but the increased near vision demands may elicit near vision symptoms sooner, when compared to an individual working in a lower income outdoor environment. As with any disease, having access to good education and care is important to maximise awareness and for optimal management of presbyopia.

RISK FACTORS FOR EARLY ONSET OF PRESBYOPIA

Comprehensive history taking may identify clues as to those more likely to have presbyopia sooner than usually expected (Figure 5).

In general, environmental aspects, such as living in closer proximity to the equator, at lower altitudes where temperatures are hotter, and in areas with greater toxic exposure, have been associated with earlier onset of presbyopia. There have been inconsistent findings related to UV, however there may be benefits from using UV blocking devices to maintain accommodation ability for longer periods.

A poor diet, especially with insufficient essential amino acids or antioxidant nutrients, may induce presbyopia earlier as these help support healthy functioning of the crystalline lens.

Of interest is how the use of digital devices is influencing our near demands and accommodation amplitude, potentially contributing to the emergence of presbyopia.

Refractive error has been linked to the inception of presbyopia based on the logic that eyeball size may influence accommodative power and due to changes to accommodative demands from different powered spectacle lenses. This suggests spectacle corrected hyperopes become presbyopic earlier than those with no or myopic refractive errors.

Of note, some individuals will naturally have lower than average accommodative amplitudes or be taking medications that block acetylcholine neurotransmitters, which reduce accommodative ability. Some examples include:

• Anticholinergics,

• Antipsychotics,

• Antihistamines,

• Antidepressants/Anti-anxiety drugs

Diuretics can also lead to lenticular dehydration through changing the balance of fluid. Some non-prescription/recreational drugs can also have consequences resulting in accommodation disorders, which may be transient changes or dosage related.

On the other side of the coin, some medications, such as pilocarpine, may potentially hinder the birth of presbyopia by stimulating muscarinic receptors and accommodative activity.

Any ocular condition that causes damage or impact to the lens or ciliary muscle is more likely to induce presbyopia, for example trauma, aphakia, iridocyclitis, and Aide’s syndrome. Associated systemic conditions include:

• Diabetes,

• Multiple sclerosis,

• Myasthenia gravis,

• Down’s syndrome, and

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV ).

Good sleeping patterns are beneficial for many reasons and may have protective properties which contribute to helping reduce presbyopia progression according to one study.6 Ageing reduces the amplitude of the circadian rhythm and its response to light; older age has been associated with sleep disorders.6

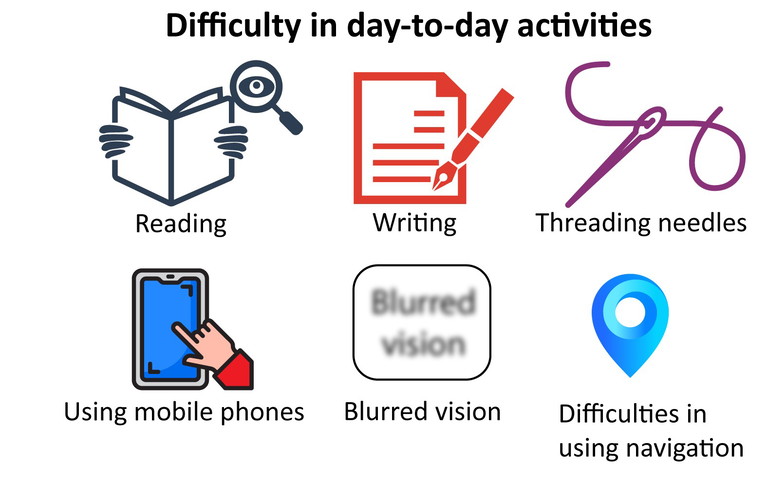

Figure 6. Examples of difficulties with everyday activities for those with presbyopia.

QUALITY OF LIFE IMPACT

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are a useful way to determine how presbyopia may be impacting an individual’s quality of life. Several presbyopia specific questionnaires have been developed and some examples include:

• Near activity visual questionnaire (NAVQ),

• Near vision-related QoL questionnaire (NVQL),

• Presbyopia impact and coping questionnaire (PICQ),

• Near vision presbyopia task-based questionnaire (NVPTQ), and the

• Activities of daily living (ADL) framework.

There are also relevant non-presbyopia specific questionnaires that can be effective for comparing presbyopia treatment options. For example, the National Eye Institute refractive quality of life (NEI-RQL) has been used to reveal a better outcome and functional vision preference for multifocal contact lenses over monovision contact lenses. There are also positive PROMs findings for surgical options. Given the vast range of optical and surgical options available for presbyopia, understanding the patient’s visual and lifestyle needs is important to ensure the best recommendations. Good product/lens design knowledge and keeping pace with new offerings are important to ensure the most suitable options are discussed.

These management solutions do not cure presbyopia and can come with frustrations, for example the steaming up of spectacle lenses, breaking/losing eyewear, or the inconvenience of having to use a near optical correction. There is also the potential for activity limitations (Figure 6) including reading, writing, seeing digital screens, recognising faces up close, cooking, needle work, applying makeup and cutting finger/ toenails. The increasing difficulty performing close tasks has been linked with the amount of presbyopia. In some cases, hobbies may be ceased or engaged with less enthusiasm due to the near visual challenges.

Coping strategies include increasing font size, use of spectacles/contact lenses, holding near material at increasing distance (the ‘trombone effect’), squinting when reading, use of additional lighting, or simply relying on others.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND HEALTH IMPACT

The consequences of presbyopia differ between individuals; for some it is one of the first realisations of getting to a certain age milestone and can generate emotional responses such as feeling self-conscious, old, denial, embarrassment, anger, insecurity, low sense of accomplishment or fear of presbyopia progression.

To measure the psychological impact of a disease, researchers often use a ‘time trade-off ’ concept, where those with the disease are asked how many years of their lifetime they would sacrifice to be free of the condition. For presbyopia, the outcomes were similar to distance vision impairment and hypertension.

Presbyopia has been associated with depression and anxiety. Medications often taken as part of treatment plans for these conditions have the potential to induce issues with accommodative functionality. If the person becomes more socially reclusive, develops unhealthy habits, and decreases fitness related activities, this could elicit physical as well as mental health issues.

The risk of falls is higher in those over 65 years old (30–40% may fall once a year), meaning carefully consideration of the best eyewear solutions with appropriate advice is important.

FINANCIAL BURDENS

The estimated global cost of correcting presbyopia is an incredible US$30 billion and using the appropriate correction can increase work productivity.7 A study of Indian tea workers showed a 20% increase in work productivity by simply providing near vision spectacles.8 The BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia report reveals sub-optimal correction has been found to lead to a greater than twofold increase in near task difficulty and having the most beneficial correction option for the individual’s needs is linked to increased productivity-adjusted life years.

The report also details the financial implications to the individuals, society, and employers. For those with presbyopia, the cost of purchasing eye care services/products could result in a low personal spend of somewhere in the region of $5 every three years (if favouring off the shelf reading spectacles without any eye services) to more than a whopping $4,000 per year (for those investing in multiple options including surgery and the associated eye appointment costs). Most are likely to spend somewhere on this spectrum, with the majority of the cost dependent on the management/ frames and lenses and/or contact lenses selected. Additional costs may come from investing in better lighting and spectacle cleaning products.

Unfortunately, difficulties with access to eye care and/or the associated costs result in some people trying to cope without the best correction for their presbyopia, especially in low income areas.

While the benefits of presbyopia correction are generally appreciated, there are plenty of patients who willingly share their experiences of needing to borrow a colleague’s spectacles to better conduct near tasks, or the temporary hindering of performance during the adaption period to new eyewear. If fatigue or symptoms result, this could lead to time off work, mistakes, avoiding near vision tasks, or the perception that this could influence their chances for future career opportunities.

Employers may have increased costs in supporting employees, for example when supplying presbyopia specific safety eyewear, from loss of productivity and when covering periods of absence. A data modelling study estimated that the potential productivity loss related to a lack of correction for presbyopia could be $25.4 billion or 0.037% of the global gross domestic product.9 The risk of workrelated injuries has also been reported to be higher for those with presbyopia; one study found older welders were 4.2 times more likely to have an ocular injury than those younger “free of presbyopia” welders.10 For occupations where minimum near visual standards have been recommended, these are frequently not met. One study of dentists found most (93.5%) who were likely to have presbyopia (45 years old and above) did not achieve the minimum recommended near vision work requirements.11

SUMMARY

Presbyopia is common and the numbers are growing. Luckily the condition is easily managed with optical and/or refractive surgery, although using these solutions can come with frustrations and inconveniences. There is a need for a universally agreed definition, which the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia publications now provide. Standardising future research approaches will enable for better comparisons of the literature.

As eye care professionals (ECPs), we have an important role in supporting those with presbyopia and addressing the lack of awareness or, in some cases, denial. We should be empathic as to how presbyopia may mentally and financially impact an individual and adapt our communication style accordingly. Uncorrected/sub optimal correction of presbyopia can result in a substantial burden, and reduced quality of life and productivity, which impacts the individual, society, and economy.

A proactive approach will help identify risk factors and signs in those approaching presbyopia. For example, a person of 35 years+ with asthenopia during prolonged near vision on digital devices may present earlier than typically expected, as might those taking certain medications that reduce accommodation ability.

A comprehensive history, clinical assessment, and visual task analysis are keys to ensuring management discussions best match the patient’s needs. Most likely, several eyewear options will provide the best outcomes and often the reason given by patients for not adopting certain presbyopia solutions (for example, contact lenses) is the lack of recommendation by the ECP.12 The preferred choices will change with time, in line with the evolving demands of the patient, with introduction of new technology/products, and simply reflecting that presbyopia is not a static condition. Discussions should include relevant supplementary advice on aspects including work ergonomics and the benefits of lighting.

Figure 7. BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact authors.

Presbyopia and age associated changes are likely to be contributing factors to wider issues including health conditions and through regular eye screening we can help detect red flags and make a significant difference to our patients’ lives.

Acknowledgement and recognition to the authors of the original paper: Maria Markoulli, Timothy Fricke, Anitha Arvind, Kevin Frick, Kerryn Hart, Mahesh Joshi, Himal Kandel, Antonio Macedo, Dimitra Makrynioti, Neil Retallic, Nery Garcia-Porta, Gauri Shrestha, and James Wolffsohn (represented in Figure 7).

Figures 2,3,4, and 6 and Table 1 have been published with permission.

The full report can be accessed at BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Epidemiology and impact in Contact Lens and Anterior Eye available at: contactlensjournal.com or by following the QR code.

BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia was facilitated by the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA), with financial support by way of educational grants for collaboration, publication and dissemination provided by Alcon, Bausch and Lomb, CooperVision, EssilorLuxottica, and Johnson and Johnson Vision. The editors for the series are Neil Retallic and Dr Debarun Dutta.

BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia was facilitated by the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA), with financial support by way of educational grants for collaboration, publication and dissemination provided by Alcon, Bausch and Lomb, CooperVision, EssilorLuxottica, and Johnson and Johnson Vision. The editors for the series are Neil Retallic and Dr Debarun Dutta.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit mieducation.com/bcla-clear-presbyopia-epidemiology-and-impact.

Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience working in practice, education, industry, and head office roles. He currently works for Specsavers and the College of Optometrists in the United Kingdom and is a Past President of the British Contact Lens Association. He is completing a PhD on mental welfare and burnout among the profession.