mieducation

Perfecting the Art of Pterygium Surgery

Pterygium is one of the most common ocular surface lesions in Australia, with a prevalence of 7.3% in a population-based study in the Blue Mountains, New South Wales, Australia.A pathology-based incidence study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) in Queensland demonstrated a rate of 1.9 new cases per 100,000 residents.1 2

Medicare data over the past decade indicate that excision of the pterygium combined with a conjunctival autograft is now the preferred method of pterygium treatment, accounting for more than 88% of all pterygium surgeries in Australia.This is excellent news given the complications associated with other forms of treatment previously used in Australia such as beta irradiation (1960s to the 1990s) and the use of chemo-adjuvant therapies, principally mitomycin C. 3

P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium – the pterygium extended removal followed by extended conjunctival transplant for pterygium technique – pioneered, invented, and perfected over 25 years by Professor Lawrence Hirst, has led to several thousands of patients benefiting from the treatment of their pterygia.

The evidence basis for P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium is the largest, consecutive, prospectively collected database with the longest follow-up of patients using this highly standardised technique. The strengths and limitations of the technique have been extensively published in the peer reviewed literature.

WRITERS Dr Tanya Trinh and Professor Lawrence Hirst AM

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Recognise the signs of pterygium and its impact on vision and cosmesis,

2. Be aware of conditions potentially masking as pterygium,

3. Understand the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium surgery technique and its advantages, and

4. Realise the need for patient education and post-operative care.

A pterygium is a relatively common fleshy, fibrovascular proliferation of Tenons and conjunctiva that encroaches upon the cornea, resulting in ocular irritation, visual loss, and rarely, restrictive diplopia.3 Prevalence varies widely in the peer reviewed literature with geography, age, and gender, and is 10% in Queensland and not much less in NSW.1

Overwhelmingly there appears to be an association with increased ultraviolet (UV) light exposure associated with peri-equatorial countries. This may explain the propensity of patients with a history of increased outdoors work having a higher incidence of pterygium.4

Over the past 25 years the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium technique, developed by Professor Lawrence Hirst, has focussed on the evidencebased treatment of pterygia to provide the best results in pterygium surgery in the world.5

There is a very small cohort of surgeons trained in this specialised technique, and we are exceptionally proud of its track record of more than 30 peer-reviewed publications proving the lowest recurrence rates, very low complications, and excellence in cosmesis in some of the premier international journals.

The three main concerns that patients voice about pterygia are (A) will this return, (B) what will my eye look like after surgery and (C) what are the risks associated with pterygium surgery? This article aims to provide information in a user-friendly framework designed around these patient concerns, and to answer the most common pterygium queries raised by the optometric community.

INDICATIONS FOR PTERYGIUM REMOVAL

Pterygium surgery should not be viewed as a trivial surgery and should not be contemplated unless there are compelling reasons to proceed. As a result, many patients who are not bothered by their pterygium, and where there are no indications for intervention, are sent back to referring optometrists to monitor them annually until their pterygium genuinely warrants surgery.6 It is important that a decision to refer for surgery is based on the patient’s best interests only.

Surgery is recommended where:

1. Vision is affected or threatened, either by direct obstruction (lesion growing over or close to the pupil, usually 2.5–3 mm over the limbus) or increasing astigmatism,

2. A patient suffers from chronic irritation, injection, epiphora, and foreign body sensation requiring daily eye drops,

3. A patient requires, or wants, cataract removal or refractive surgery. In such patients the removal of even a relatively small pterygium is justified to allow the cornea to return to a stable astigmatic state prior to further refractive surgery. Failure to remove the pterygium first may result in some very unfortunate refractive results after cataract/refractive surgery,

4. There is restrictive diplopia, inability to be fit with a contact lens, or suspicious appearance suggestive of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN),

5. The patient is subjected to discrimination at work etc. as a result of a red eye, which may be considered by others to be due to substance abuse etc., or

6. Patients are distressed by the appearance of the eye, given the cosmetic results that P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium can achieve.

It is impossible to predict the extent of pterygium growth, although most will stop growing at some time. The patient must be made aware that even with successful surgery using P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium, some corneal opacity (a corneal footprint, if you will) underlying the pterygium may remain and can require further treatment, such as phototherapeutic keratectomy, prior to cataract surgery.

PTERYGIUM REMOVAL WITH CATARACT PRESENCE

Evaluation of a patient with coexistent cataract and pterygium must include advice to have the pterygium removed at least three months before the cataract surgery. This will allow the cornea to return to a stable curvature and an accurate intraocular lens calculation to be undertaken.

Otherwise, simultaneous cataract and pterygium removal may well result in some unpleasant refractive outcomes, which will mean an unhappy patient, unhappy referring optometrist, and a very unhappy – but hopefully now wiser – ophthalmic surgeon. Removal of pterygia after cataract surgery can result in refractive changes that are less satisfactory for patients. It is important that the referring optometrist advises the patient about this situation and that this is reiterated at the surgical consultation.

PTERYGIUM OR SOMETHING MORE SINISTER?

Both pterygium and OSSN, or dysplasia, are related to ultraviolet irradiation, and unsurprisingly can occur simultaneously – in as many as 10% of patients who have pterygium surgery. As OSSN is often not clinically visible at the slit lamp, the surgeon should always send the pterygium specimen for pathology.7 The typical OSSN, not associated with a pterygium in the same patient, usually has corkscrew vessels and the lesion is usually elevated off the ocular surface.8 However, if in doubt, the patient should be referred for assessment, which may include a biopsy. Abnormal pigmentation of a growing surface lesion should be considered worthy of referral in case it is a conjunctival nevus or melanoma.

DIFFERENTIATION OF PTERYGIUM FROM A PINGUECULA

In general, optometrists are readily able to differentiate these two lesions, with the pinguecula not extending over the limbus. In 2018 we published a study of 1,511 consecutive patients where 16% of incorrect diagnoses between these two lesions were made by general practitioners compared to 1.4% by optometrists. General practitioners were, therefore, 13.28 times more likely to incorrectly diagnose a pterygium than optometrists (95% CI 7.48–23.57).9

WHAT DOES P.E.R.F.E.C.T. FOR PTERYGIUM OFFER?

How do P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium surgery results differ from standard pterygium removal techniques? We recently had the honour of having our prospective study of 3,980 pterygium patients (3,459 primary pterygia and 521 recurrent pterygia) accepted for presentation at the 2024 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons Annual Meeting.10 We were able to demonstrate the following results of the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium:

• Recurrence rate of primary pterygium removal was one in 3,459 cases (0.028%),

• Recurrence rate of recurrent pterygium removal (where the original surgery was performed with other techniques elsewhere) was two in 521 cases, where one of these was a conjunctival recurrence only,

• The mean pterygium size onto the cornea was 3–4 mm (so these were not trivial sized pterygia),

• Over 72% of all cases presented between ages of 40–69 years, and were more commonly men (58%), and

• Over 500 of our cases were recurrent pterygia with the same age distribution as for primary pterygia.

These are the lowest recurrence rates in the largest prospective, single surgeon, cohort series in the world’s peer-reviewed literature.

“simultaneous cataract and pterygium removal may well result in some unpleasant refractive results, which will mean an unhappy patient, unhappy referring optometrist, and a very unhappy – but hopefully now wiser – ophthalmic surgeon”

RECOVERY: WHAT PATIENTS EXPERIENCE

Knowledge about post-operative recovery is important as patients require support and education about the healing process. Patients may initially experience mild-to-moderate pain, which typically subsides within 24 hours after surgery and is managed effectively with prescribed medications. With P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium, patients typically require about two to four paracetamol/codeine tablets in the first 24 hours. A patch is worn from the time of surgery to the first postoperative visit (the next day). Once it is removed, 80% of patients require no further pain medication.11

It is normal for the eyelid to be swollen, for the vision to be slightly blurred, and for the patient to experience mild epiphora and photosensitivity. Diplopia looking towards the side of the pterygium is relatively common for a few days and is gone within a week in 97% of patients. As a result, the patient should be advised not to drive or undertake any potentially dangerous activities until the diplopia has resolved. The patient is advised to keep the eye dry for two weeks using a patch when showering.

The patient is given an antibiotic drop, usually chloramphenicol four time a day for a week only, prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte) every two hours while awake for the first three weeks, and then four times a day for a further three weeks. The sutures most commonly used will have resorbed in two weeks.

Post operative visits may often be shared with the referring optometrist, with particular reference to intraocular pressure measurement to exclude a steroid induced pressure rise that may require temporary treatment. The eye should be white and quiet by four to six weeks.11

PATIENT EXPECTATIONS

Pterygium and Cosmesis

Patients may well have considerable expectations about the cosmetic result, and this is another area where P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium excels. In 2011, we published an objective, web-based grading system for cosmesis of patients who underwent P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium for primary nasal pterygia. In a randomised controlled trial, a study trained six cornea specialists and six lay patients to grade post operative appearances with the use of standardised photography.12

The graders were given 20 seconds to grade the images (compared to real life where impressions are instantaneous) and the images presented were magnified on screen (up to 10x magnification on a 24-inch screen monitor, compared to real life where the eye is viewed at conversational distance). The images used were taken within the first three months of surgery (with known improvement of cosmetic appearance continuing for six to 12 months after surgery).

Furthermore, a conservate grading system was used, as follows:

• ‘Poor’, where there was evidence of conjunctival recurrence (an arrowhead formation of puckered conjunctiva aimed at the limbus or any other conjunctival abnormality like folds or scars),

• ‘Fair’, where evidence of the pterygium removal was limited solely to vascular changes (either injection or abnormal vascular complexes) in the area of excision,

• ‘Good’, where generalised conjunctival injection or vascular plexuses were seen but not restricted to the area of excision (frequently seen in otherwise normal eyes),

• ‘Excellent’, where the appearance was the equivalent of normal, except for some corneal opacity, and

• ‘Normal’, where the appearance was indistinguishable from a normal eye.

It should be noted that all grading above ‘poor’ had to demonstrate no conjunctival tissue abnormalities with a flat conjunctiva and no obvious scars.

“This explains why ‘Your first go is your best go'”

After training on the web-based grading system, intra-observer reliability scores were 0.86 to 0.95 for lay graders and 0.90 to 0.92 for ophthalmologist graders. In this study of 120 control (unoperated) eyes and 120 operated eyes, 94% of cases undergoing P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium had a cosmetic appearance equivalent to a ‘good’ looking eye, defined as an eye with no conjunctival abnormalities apart from some vascular changes indistinguishable from a normal control eye. With P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium, most patients may expect an aesthetically pleasing result that is virtually indistinguishable from a normal eye.12,13

In my practice, the entire eye is photographed (lateral, medial, superior, and inferior as well as en face view) and displayed and discussed with the patient as part of their education and consent process. One of the more useful aspects of this approach is demonstrating that the entire scleral surface is already covered with smaller calibre blood vessels distributed throughout the normal conjunctiva (that normally exist without intervention) and that the eyeball is not actually ‘white’; this assists in setting realistic patient expectations. After the surgery, the eyeball is photographed again using the same approach (for consistency of comparison) at the three-month mark, shown to the patient, and also sent back to the referrer.

Pterygium and Dry Eye Disease

Patients should be aware that pterygia and dry eye disease commonly co-exist, and that the surgical removal of a pterygium will not cure the dry eye component of their ocular discomfort. Treating the dry eye component will also not ‘treat’ the pterygia, which can be a source of patient frustration if adequate time is not spent on differentiating the two conditions for the patient’s edification. For this reason, the concurrent documentation, education, and treatment of dry eye should be commenced prior to surgery, with an emphasis on the need for continued management post operatively.

Preservative free topical lubricants used liberally can be helpful as a temporising measure for ocular foreign body sensation. Topical immunomodulators, such as cyclosporin or lifitegrast, may be considered in conjunction with preservative free lubricants, and may require an induction period (two to six weeks). A brief fluorometholone- assisted induction regime is not uncommonly used to assist transition onto the topical immunomodulators; however, patients should be aware that all these approaches are focussed on treating the concurrent dry eye component of their disease. Occasionally, however, these approaches are adequate in temporising ocular surface symptoms until such point that the patient is ready for surgery.

Patients may often present with pre-existing and liberal use of ‘anti-red eye’ drops containing vasoconstrictors to treat their injected ocular appearance. These patients must be educated that the rebound effect of these topical medications may worsen the cosmesis of the eyes upon withdrawal.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A PTERYGIUM RECURS?

The risks of recurrence with poor surgical technique of pterygia removal include injection, increased vascularity, marked fibrotic scar, proud flesh, inflammation, loss of vision via rapid and aggressive encroachment of the recurrence over the corneal surface, and restrictive diplopia. Of these, the latter two complications related to recurrence are the most concerning for patients. In our approach, the subsequent disorganisation of the Tenon tissue and involved scarring around the recti can double the time required for successful removal of the recurrent pterygium. This means that removal is much more challenging and the resultant cosmesis may be less than ideal. This explains why ‘Your first go is your best go’.

RISKS OF P.E.R.F.E.C.T. FOR PTERYGIUM SURGERY?

The international published literature shows a risk of recurrence after primary pterygium surgery using standard techniques between 6.7% to 88% depending on the method used.14

The published rate of P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium is now one in 3,459 cases (0.028%).11 It is important to note that this study included prospectively collected data of 3,980 consecutive pterygium patients, and that the average size of the pterygia was 3–4 mm horizontally and 8–10 mm vertically onto the cornea in 75% of patients – so these were significantly sized pterygia.

We removed only 20 significant pingueculae during these 25 years because of persistent irritation or concerns about the cosmetic appearance. The surgery was identical to that for a pterygium, except there was no disturbance of the cornea.

When reviewing our case series on this technique, we found that other risks may include a one in 400 risk of conjunctival cyst or ‘proud flesh’, or infection requiring additional treatment. The risk of post operative conjunctival autograft swelling requiring replacement was one in 500, with one in 1,000 patients requiring surgical intervention for persistent diplopia. A risk of ptosis requiring surgical intervention is one in 1,000.15

Other risks common to all eye surgery include infection (one in our entire series) and loss of all vision in an eye as a result of uncontrolled infection or perforation of the eye (none in our series).

WHERE IS P.E.R.F.E.C.T. FOR PTERYGIUM PERFORMED IN AUSTRALIA?

This technique is currently being offered by five P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium fellowshiptrained surgeons, who are listed below. All fellows have undertaken 12–18 months of dedicated pterygium surgical training under Professor Hirst’s guidance with a minimum of 40 primary surgeon cases performed to his stringent requirements.

1. Dr Todd Goodwin (QLD) 2. Dr Brett Drury (QLD and NSW) 3. Dr Juanita Pappalardo (QLD) 4. Dr Katherine Smallcombe (QLD) 5. Dr Tanya Trinh (NSW)

Professor Hirst has now retired from clinical practice as of January 2024.

IS THIS TECHNIQUE OFFERED OUTSIDE AUSTRALIA?

There are currently no P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium fellowship-trained surgeons outside of Australia and as such, many patients from the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and other countries have flown in to seek treatment. If doing so, the recommendation is to stay a minimum of 10 days after surgery, with subsequent coordination and follow-up being performed at home with their usual ophthalmologist.

“The treatment of pterygia should not be considered trivial surgery”

CONCLUSION

The treatment of pterygia should not be considered trivial surgery and should be undertaken by specially-trained ophthalmologists because of the risk of recurrence, which increases the patient’s risks of further recurrence and a poor cosmetic outcome. Optometrists are very skilled at detecting pterygia compared to general practitioners and should be the mainstay of the first assessment of diagnosing ocular surface lesions including pterygia with subsequent referral to specialty-trained ophthalmologists. The meticulous and extensive removal of underlying Tenons with the use of an extended conjunctival autograft using P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium has resulted in the lowest recurrence (nearly 0%) and a good cosmetic appearance in the largest study of pterygium removal in the world’s literature.

To earn your CPD hours from this activity, visit: mieducation.com/perfecting-the-art-of - pterygium-surgery.

References available at mieducation.com

CASE STUDY: WHY YOUR FIRST GO IS YOUR BEST GO

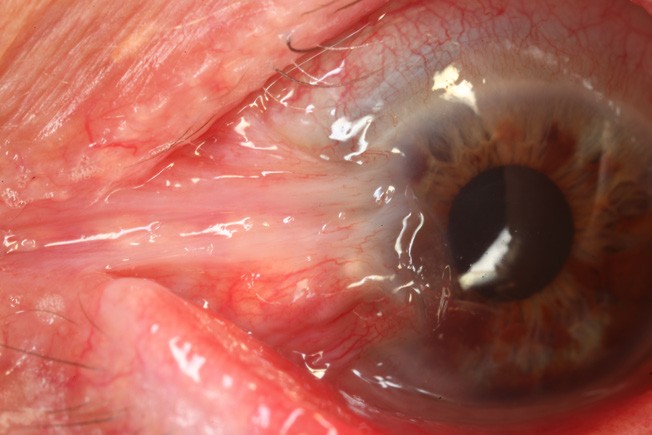

A 72-year-old male retiree was referred to The Australian Pterygium Centre in January 2023. He was concerned about the rapid and aggressive recurrence of his left nasal pterygium, which underwent surgery elsewhere in 2021, and his resultant binocular horizontal diplopia.

His past ocular history was otherwise remarkable for ocular hypertension for which he took latanoprost in each eye nightly, and bilateral early cataract. His unaided visual acuity was R 6/9 and L 6/18. Both eyes improved to 6/7.5 on pinhole. The maculae and discs had a healthy appearance.

On slit lamp examination, the patient exhibited an injected, vascular, elevated pterygium recurrence spanning 3.5 mm from limbus to apex and approximately 135º circumferentially. There was significant tethering to the point that the patient was unable to abduct the eye past the midline, causing horizontal binocular diplopia. Significant traction was noted at the semilunar fold, as well as significant scarring at the prior donor and pterygium site. Symblepharon was also present as well as a mild ptosis.

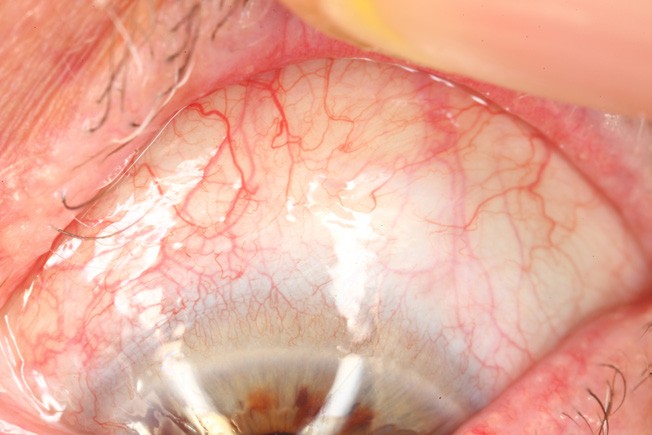

The patient underwent extensive counselling and was consented on the increased risk of scarring, residual diplopia, worsening ptosis, and recurrence when treating recurrent pterygia on top of the risks of P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium surgery. Surgery was performed in March 2023. An autoconjunctival graft was able to be successfully harvested from the superior bulbar conjunctiva, despite scarring from a previous graft retrieval, and sutured into place.

Figure 1. Preoperative photo of patient with severe restrictive diplopia due to symblepharon formation after multiple attempts at treating pterygium recurrence.

Figure 2. Pre-operative status of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, demonstrating the health of the donor site.

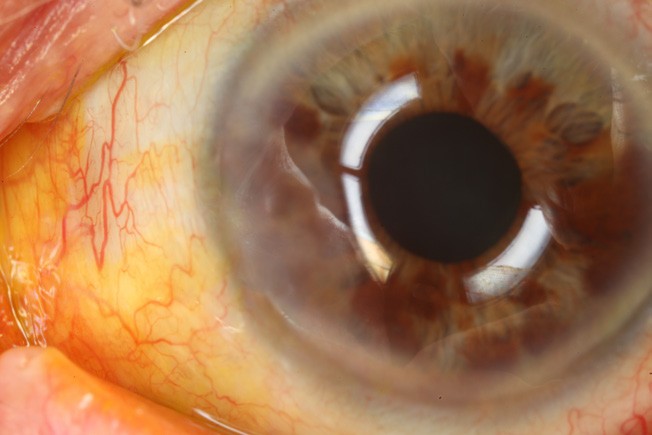

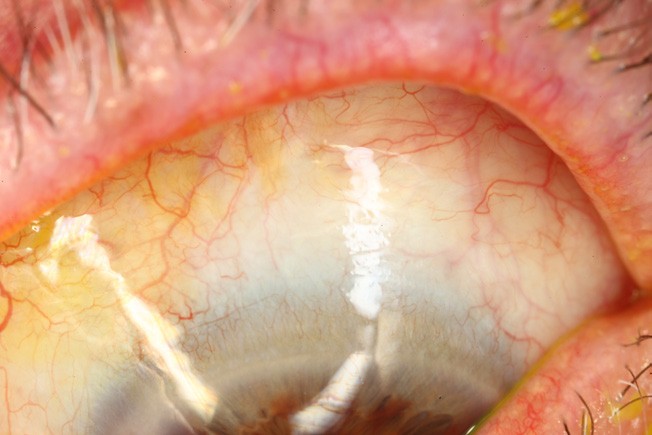

Figures 1–4 represent the before and after of his treatment with the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium technique for his severe recurrent pterygium. The patient remains recurrence free at 24 months post-surgery with no corneal opacity and almost complete resolution of his horizontal binocular diplopia. His left visual acuity remained at 6/18 and he is undertaking cataract surgery to further improve his vision.

CASE LEARNINGS

Recurrent pterygia are extremely challenging surgical cases because of extensive scarring at the pterygium site and at the graft site. But with P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium a satisfactory result is almost always achieved, despite slightly increased risks of recurrence. Our recurrence rate was two in 502 or 0.39% in recurrent pterygium cases where the primary surgery was performed elsewhere, compared to primary pterygium removal where our recurrence rate was one in 3,459 cases or 0.028%. This case demonstrates the aggressive nature of early recurrences and why the first attempt at pterygium removal is ‘the best go’ to avoid this type of recurrence.

This case also demonstrates the results that can be achieved with meticulous attention to pterygium recurrence removal using the same principles for primary pterygium removal with P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium, without reliance on toxic chemical treatments during or after pterygium removal.

Figure 3. Postoperative image, with fluoroscein staining, of a patient treated with P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium.1

Figure 4. Postoperative image of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, demonstrating the cosmetically acceptable appearance of the donor site.

Dr Tanya Trinh BAppSci (Med Sci) MBBS FRANZCO FWCRSVS FEBOSCR Physcian CEO is an Australian ophthalmologist specialising in complex cornea, cataract, and refractive surgery. She is a fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmology and in 2023 became the first Australian female to be awarded a fellowship of the World College of Refractive Surgery and Visual Sciences. She co-directs Australia’s only Keratoprosthesis Service and teaches at the University of Sydney, University of Toronto in Canada, and the University of Queensland.

Visit: drtanyatrinh.com.

Professor Lawrence Hirst AM MBBS Hons MD MPH DO FRANZCO FRACS Cert.Am.Bd.Ophth graduated from the University of Queensland in 1969 and has earned a list of high achievements at some of the finest medical institutions in the United States of America and in Australia.

His clinical achievements are well known and include techniques for the application of tissue adhesives in perforated eyes and corneoscleral grafts. Professor Hirst pioneered the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for Pterygium technique and in 2011 established The Australian Pterygium Centre, an entire clinical practice dedicated to treating pterygium. He was made a member (AM) in the general division in the Queen’s Birthday 2018 Honours list.