mieyecare

Improving Care

for People with Usher Syndrome

WRITERS Associate Professors Lauren Ayton and Karyn Galvin, and Emily Shepard

Usher syndrome, first described by Scottish ophthalmologist Charles Usher in 1914, is a rare genetic disorder characterised by hearing loss and vision impairment. Dr Usher observed this condition in families in which individuals experienced both deafness and progressive vision loss, identifying it as a distinct syndrome with dual sensory deficits.

In this article, Associate Professors Lauren Ayton and Karyn Galvin, along with Emily Shepard, provide clinical pearls for the diagnosis of Usher syndrome, highlight the importance of multidisciplinary management of this condition, and provide an insight into future treatments.

Over time, advancements in clinical and genetic research have elucidated the underlying causes and variations of Usher syndrome. It is now known that some subtypes of this condition also include vestibular problems, leading to issues with balance and the development of gross motor skills in children. Ten different genes have been identified that are linked to Usher syndrome,1 and we now have access to genetic testing, which allows the diagnosis of children at a very young age. Despite the progress made, cohesive and comprehensive management of people living with Usher syndrome remains an unmet goal.

A significant challenge in the clinical care and support of people with Usher syndrome is the multiplicative effects of the condition. Rather than just dealing with one sensory loss, such as vision impairment, individuals are dealing with several.2 Hence, comprehensive clinical care and support is vital. People living with the condition, and their families, often report segmented and siloed healthcare experiences.3 An audacious goal for our team, and others in the field, is to see a world where these siloes are broken down, and all people with complex conditions such as Usher syndrome receive best-practice multidisciplinary care.

CLASSIFICATION, INHERITANCE, AND GENETIC DIAGNOSIS

Usher syndrome affects around four to 17 in 100,000 people,4 but is the most common cause of deaf-blindness globally. The syndrome is thought to be responsible for the hearing loss in up to 12% of all children who are either deaf or hard-of-hearing.5

The condition is caused by damage to the sensorineural cells in the ear and eye (cochlear hair cells, and retinal photoreceptors, respectively). It is a monogenic condition, with autosomal recessive inheritance. This inheritance pattern means that Usher syndrome often ‘skips’ generations, and unaffected parents can have a child with the condition. If two parents are both carriers of an Usher gene (with one healthy and one disease-causing variant), then each of their children has a:

• One in four chance of neither having Usher syndrome, nor being a carrier of the gene,

• Two in four chance of being an unaffected carrier, and

• One in four chance of having Usher syndrome.

Usher syndrome is classified into four main types – Usher syndrome type 1 to type 4 (USH1 – USH4) – each characterised by genetic cause, disease severity, impact on body systems and age of onset. Types 1 and 2 are the most common overall, but there are ethnic differences. For example, in certain populations in Finland and in people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, Type 3 is disproportionately represented.

It is important to note that some of these genes can also cause isolated retinal degeneration, without hearing loss. For example, USH2Aassociated retinitis pigmentosa does not have the syndromic manifestations.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

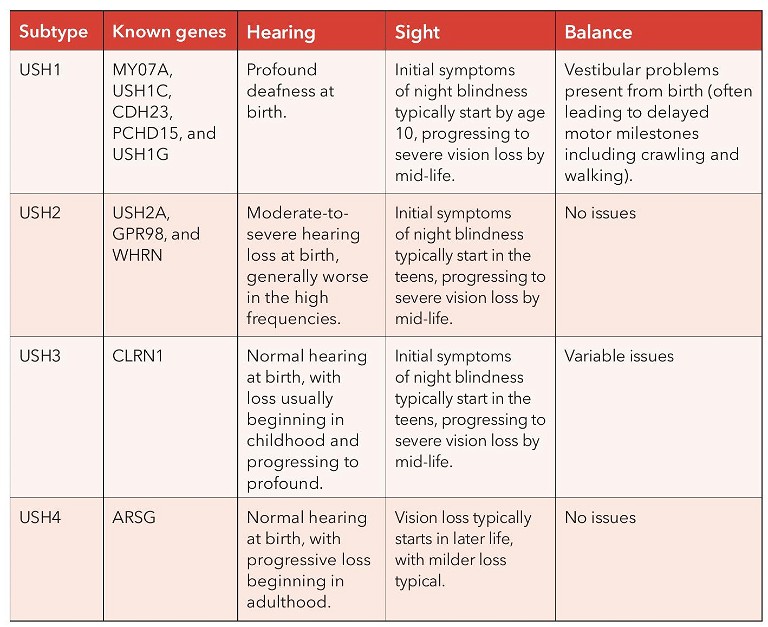

The signs and symptoms of Usher syndrome vary by subtype, as outlined in Table 1. All people with Usher syndrome will experience some degree of both vision and hearing loss, with USH1 and USH3 also associated with vestibular dysfunction.

Hearing Loss

Individuals with Usher syndrome experience varying degrees of hearing impairment, ranging from mild to profound. In USH1, severe to profound congenital deafness is observed, while USH2 and USH3 typically present with moderate-to-severe hearing loss from birth or early childhood.

Vision Impairment

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a degenerative eye condition affecting the retina’s photoreceptor cells, is the cause of vision loss in Usher syndrome (Figure 1). Progressive vision loss occurs, often beginning with night blindness in childhood. This deterioration advances to peripheral vision loss, leading to tunnel vision or blindness by adulthood. As in nonsyndromic forms of RP, people with Usher syndrome are also at risk for early cataract development and macular oedema, both of which can contribute to vision loss.

Vestibular Dysfunction

Some individuals may experience vestibular dysfunction due to abnormalities of the hair cells in the vestibule, the sensory organ for balance located in the inner ear. This can lead to problems with balance, coordination, and spatial orientation. Due to these effects, infants with Usher Type 1 have challenges sitting without support, and rarely walk before 18 months of age. These difficulties are often the first signs that a child who is congenitally deaf may indeed have a more complex syndrome.

MANAGEMENT

Currently, the management of Usher syndrome addresses the sensory losses, with no curative treatments available. The level of assistance required will vary, depending on the subtype of Usher and current stage of disease. However, early intervention is key. Providing support to children and families can lead to improved outcomes, with the individuals better equipped for the future challenges of school and workplace demands.

General management strategies follow.

Hearing Devices

Hearing aids, cochlear implants, and assistive listening devices support the management of hearing loss in individuals with Usher syndrome. These devices aim to enhance auditory input and, therefore, facilitate the development of communication abilities. In particular, if congenital or early-onset severe-profound hearing loss is present, cochlear implants at a young age lead to better hearing, speech, and cognitive outcomes.6 For individuals with progressive or later-onset hearing loss, early fitting of hearing aids facilitates the development of auditory skills and oral language. The stimulation of the auditory system via early hearing aid fitting maximises the chance of success if hearing deteriorates such that a cochlear implant is required later in life.

Vision Support

Vision rehabilitation programs and orientation/mobility training assist individuals in adapting to vision loss. Low-vision aids can aid in daily activities by maximising existing vision, and often focus on aspects such as glare reduction and improving contrast. In addition, technologies such as smart phones and text-to-speech allow information access in various formats.

“ Usher syndrome affects around four to 17 in 100,000 people ”

Regular Monitoring

Ongoing medical evaluations by multidisciplinary teams, including audiologists, ophthalmologists, optometrists, and physiotherapists (when there is vestibular dysfunction), are crucial for monitoring disease progression and implementing appropriate interventions. The complex nature of Usher syndrome means that these multidisciplinary teams are key. Currently, patients tend to be seen by clinicians at different locations, requiring repeated explanations of symptoms and poor continuity of care. We advocate for specialised services that bring the required health professions together, to provide truly multidisciplinary care.7

Patient and Family Support

In addition to clinical services, it is important that people with Usher syndrome and their families are appropriately connected within the community. UsherKids Australia was founded in 2016 by two mothers of children with Usher syndrome, Emily Shepard and Hollie Feller, to provide support, information and advocacy for these families. They can be contacted via usherkidsaustralia.com.

Figure 1. A wide-field Optos image of the retina in a patient with advanced Usher syndrome type 2 (USH2A gene mutation), showing the characteristic signs of retinitis pigmentosa (bone spicule pigmentation, attenuated blood vessels and optic nerve pallor).

“ A significant challenge in the clinical care and support of people with Usher syndrome is the multiplicative effects of the condition ”

Table 1. Signs and symptoms of Usher syndrome.

“ In addition to therapeutic research, much work is going into improving awareness, support networks, and advocacy efforts ”

THE FUTURE

Presently there is no treatment for Usher syndrome, but a number of clinical research studies are underway. Gene therapy, stem cell research, and regenerative medicine offer potential avenues for repairing damaged sensory cells, potentially restoring or improving hearing and vision in affected individuals.

In Australia, a clinical trial is underway on an antioxidant called N-acetylcysteineamide (NACA) for slowing the progression of vision loss in Usher syndrome.8 The trial, sponsored by Nacuity Pharmaceuticals, expects to have initial results this year. Clinical trial sites are available at the Centre for Eye Research Australia (Melbourne), the

“ Currently, the management of Usher syndrome addresses the sensory losses, with no curative treatments available ”

Save Sight Institute (Sydney),9 the Lions Eye Institute (Perth) and the Queensland Eye Institute (Brisbane).10

Other earlier research programs are underway to develop gene therapy, stem cell or optogenetics treatments for Usher syndrome, but these have not yet reached clinical trials in Australia.

In addition to therapeutic research, much work is going into improving awareness, support networks, and advocacy efforts for people living with Usher syndrome. These are vital in improving access to resources, funding research initiatives, and enhancing the quality of life for individuals and families affected by Usher syndrome.

Usher syndrome remains a challenging condition that necessitates ongoing research, medical support, and community engagement to improve diagnostic capabilities and management strategies, and to ultimately find potential cures or effective treatments to mitigate its impact on affected individuals.

Associate Professor Lauren Ayton B.Optom PhD GCOT FAAO is a clinician-scientist with a strong research interest in inherited retinal diseases, gene therapy and clinical trial outcome measures. Assoc Prof Ayton holds research positions in the Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences and Department of Surgery (Ophthalmology), University of Melbourne, and at Centre for Eye Research Australia, and is the Director of Innovation and Enterprise (Engagement) in the University’s Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences.

Associate Professor Karyn Galvin has been conducting research in the field of hearing since 1989. At The University of Melbourne, she works on research projects involving children and adults using tactile devices, advanced hearing aids, and cochlear implants. She gained clinical experience as a Clinical Research Fellow in the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital Cochlear Implant Clinic from 1992 to 1997.

Emily Shepard is a co-founder and Director of UsherKids Australia, bringing her perspective as a mother of a child with Usher syndrome, as well as skills from working in a commercial environment and studies in Auslan and public health. Ms Shepard is also currently undertaking a Master of Public Health through Curtin University.

References

1. Nisenbaum, E., Thielhelm, T.P., Nourbakhsh, A., et al., Review of genotype-phenotype correlations in Usher syndrome. Ear Hear. Jan/Feb 2022;43(1):1–8. DOI:10.1097/ AUD.0000000000001066.

2. Arcous, M., Putois, O., Dalle-Nazebi, S., et al., Psychosocial determinants associated with quality of life in people with Usher syndrome. A scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. Sep 2020;42(19):2809–2820. DOI:10.1080/09638 288.2019.1571637.

3. Roborel de Climens, A., Tugaut, B., Brun-Strang, C., et al., Living with type I Usher syndrome: insights from patients and their parents. Ophthalmic Genet. Jun 2020;41(3):240– 251. DOI:10.1080/13816810.2020.1737947.

4. Boughman, J.A., Vernon, M., Shaver, K.A., Usher syndrome: definition and estimate of prevalence from two high-risk populations. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36(8):595–603. DOI:10.1016/0021-9681(83)90147-9.

5. National Library of Medicine. Usher Syndrome (webpage) Available at: nidcd.nih.gov/health/ushersyndrome [accessed 23 Oct 2023].

6. Davies, C., Bergman, J., Misztal, C., et al., The outcomes of cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome: A systematic review. J Clin Med. Jun 29 2021;10(13) DOI:10.3390/ jcm10132915.

7. Ayton, L.N., Galvin, K.L., Shepard, E.R. et al., Awareness of Usher syndrome and the need for multidisciplinary care: A cross-occupational survey of allied health clinicians. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:1927–1936. DOI:10.2147/ JMDH.S411306.

8. Centre for Eye Research Australia, Safety and Efficacy of NPI-001 Tablets for RP Associated with Usher Syndrome (SLO RP) (web page). Available at: cera.org.au/trials/safetyand-efficacy-of-npi-001-tablets-for-rp-associated-withusher-syndrome-slo-rp [accessed 29 Nov 2023].

9. Save Sight Institute, Clinical Trials: Current and Upcoming Trials (webpage) available at: sydney.edu. au/save-sight-institute/our-research/eye-geneticsinherited-retinal-diseases/clinical-trials.html [accessed 29 Nov 2023].

10. Queensland Eye Institute, Clinical Trials (webpage) available at: qei.org.au/research/clinical-trials [accessed 29 Nov 2023].