miophthalmology

Improving Cataract Outcomes from the Start

WRITER Dr Christolyn Raj

How can we ensure optimal surgical results are achieved every time our patients have cataract surgery? How can we try to avoid refractive surprises? What can be done at the initial clinical consultation to help attain excellent results postoperatively? In this article, Dr Christolyn Raj offers her pearls of wisdom.

“ In many instances when it just doesn’t seem to add up, it is best to start again at the beginning ”

Cataract surgery is more than simply removing an opacified aged lens, rather it is a form of refractive surgery. Patients not only expect that their vision will be improved through surgery but also demand exceptional results. And so they should.

However, in some instances, their expectations are unachievable, and so we need to steer them in a more appropriate direction. In most cases, depending on a patient’s visual requirements and lifestyle – and thanks to the advanced technology available today – we can offer a ‘happy compromise’.

In meeting the expectations of our patients, we need accurate preparation, and this begins in the consulting room. The responsibility for a careful and comprehensive work up of any patient presenting with a cataract lies with optometrists as much as ophthalmologists, and this is where co-management can be immensely beneficial.

In this article, I have used a series of real-life clinical vignettes to illustrate the importance of assessing patients thoroughly prior to referral for cataract surgery. Through these clinical scenarios it is possible to see how identifying key features in the primary assessment may impact the surgical outcome.

THE PREVIEW PROTOCOL

A simple protocol is discussed that may be useful as a guide in day-to-day practice to ensure a thorough assessment is made.

This protocol, called ‘PreView’, is a mnemonic for Pupils, Refractive outcome, Visual field, Eye dominance and When to consider surgery.

While this protocol is ‘fit for purpose’, a modification may also be appropriate, depending on the demographics or special interest areas that best suit your practice and patient base.

Case One: The Symptoms Don’t Add Up

A 62-year-old female, Jill* was referred for bilateral visually significant cataracts reducing her vision below that of driving standards (Snellen 6/12). An active retiree who enjoys driving, playing cards, and has a broad social network, she was keen to be spectacle independent where possible.

Jill underwent routine cataract surgery with a trifocal intraocular lens.

Week one following surgery, her vision was excellent with best corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA) 6/4 in each eye and best corrected near visual acuity (BCNV) N5 at 40cm.

At the three months follow-up consultation, her vision remained unchanged. However, she reported intense photophobia, which was worse at night. On occasion, she was unable to continue driving due to intense glare and haloes.

These symptoms were somewhat unusual for a patient who had an uncomplicated procedure and post-operative course. This was unlikely to be due to poor adaptation as Jill had demonstrated through her other activities that she was able to function very well. What then was causing her symptoms?

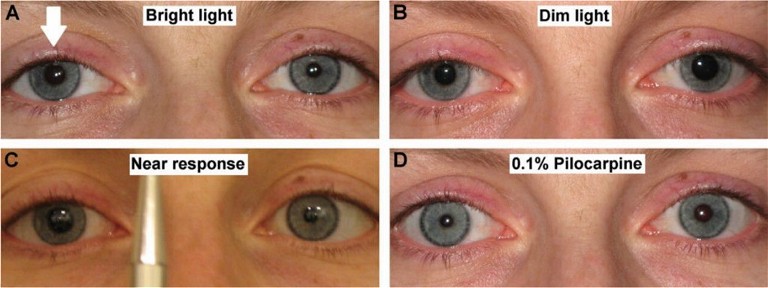

Figure 1. Pupil assessment showing light-near dissociation: Aide’s tonic pupil. The abnormal pupil is the right pupil (arrow) in A, B and C. The abnormal pupil constricts with 0.1% pilocarpine as seen in D.1

Often, when things just don’t seem to add up, it is best to start again at the beginning. Another clinical assessment was conducted with particular attention to the anterior segment, including an examination of the cornea, anterior segment, and pupils.

Measuring the pupils in light and dark showed there was a subtle anisocoria present (Figure 1). The abnormal pupil was identified as the larger pupil and further assessment revealed a light near dissociation – pathognomonic of an Adie’s tonic pupil.1

This explained Jill’s symptoms quite clearly. With the trifocal intraocular lens, and a dilated pupil, especially in dim light, she was more prone to glare symptoms that were less easy to adapt to. Thankfully, on identifying this, Jill’s symptoms were able to be treated quite conservatively with the occasional use of a drop of 0.125% pilocarpine, which causes pupil constriction without the headache side effects of 1.0% pilocarpine.2

While Jill’s experience was still a positive one, we must consider that had the pupil anisocoria been identified earlier, a discussion surrounding intraocular (IOL) lens choice and the merits of a trifocal over a standard IOL perhaps could have been detailed further prior to surgery.

Case Two: Accounting for Ocular Dominance

Mathew,* a 57-year-old male, was referred for consideration of clear lens extraction in the context of moderate myopia. Mathew works full time as a company director. The tasks of great importance to him are attending meetings and working on his computer. He had not previously had laser surgery and corneal topography revealed regular astigmatism. Once again, he had a strong desire to be spectacle independent for his work.

In many myopes, implantation of an extended depth of focus (EDOF) or trifocal IOL can be challenging and, in my opinion, are often best avoided. A monovision correction is likely to be the best option, but how do we approach this?

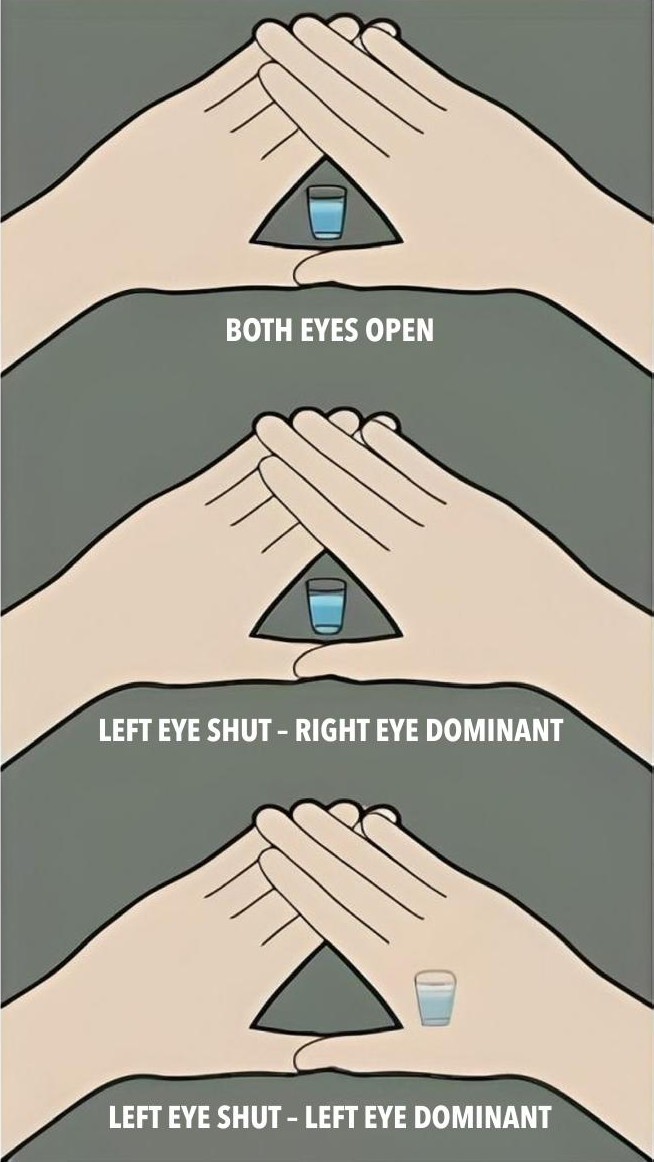

In the first instance, we need to establish ocular dominance. There are many methods to measure this. The Dolman’s test, shown in Figure 2, is routinely used in my practice and produces reliable results.3

After establishing ocular dominance, Mathew was shown a simulated version of monovision with the dominant eye being correct for distance and the fellow eye for near. This can be difficult to appreciate clinically. Co-managing with his optometrist, Mathew was given a trial of toric contact lenses to help adjust to monovision and then reviewed a few weeks later.

Modifications were made to the refractive aims of each eye, based on Mathew’s feedback wearing these lenses, and a desired refractive goal was achieved. Mathew was elated with the results.

A contact lens trial was key to Mathew’s success. Visual compromise can be difficult to simply explain, even to the most astute patients. Therefore, a demonstration with a contact lens trial is often the best option, and is ideally suited for patients who have early or no lens opacity.

Case Three: ‘Funny’ Vision

Ras,* a 65-year-old male, was referred for review of his vision and possible cataract surgery. On examination his BCVA was: R 6/9, L 6/9.

He reported that his vision was “not as good as it used to be” but he was having difficulty qualifying this. He was, however, able to describe that onset of these visual symptoms occurred about six months ago. He denied symptoms of glare or diplopia.

On examination, his lens opacities were consistent with his age; he had mild nuclear sclerotic changes.

The routine pre-op cataract assessment for Ras included corneal topography, optical coherence tomography (OCT) analysis of the macula and optic nerve, and a dilated fundus examination, which was unremarkable.

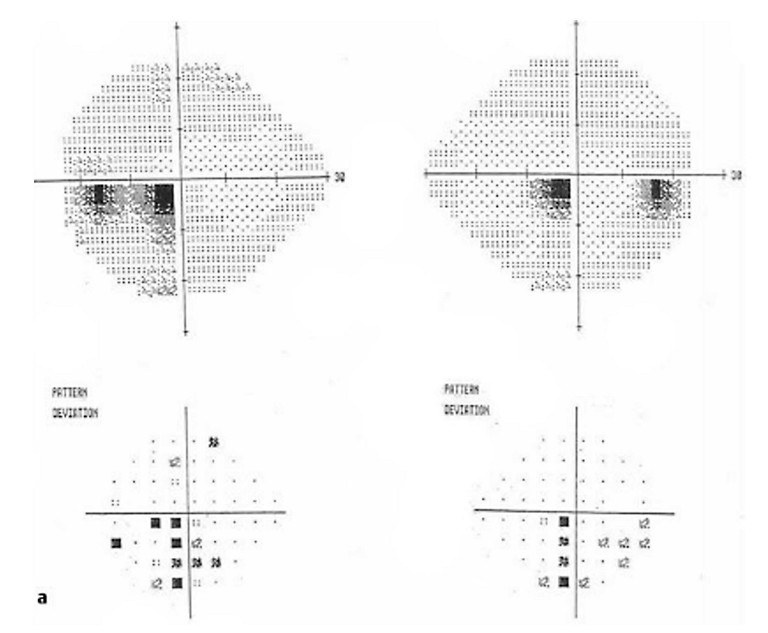

So what then was the cause of his “funny vision” with sub-acute onset? A visual fields test revealed the answer. Figure 3 shows a congruous left homonymous central scotomata.

Ras was promptly referred to neurology and underwent further neuroimaging, which revealed cerebral lymphoma affecting the occipital lobe. While an unexpected finding indeed, Ras went on to receive effective chemotherapy, which caused complete regression of the lymphoma and his visual symptoms.

This brings us to the question of whether a visual fields test should be routine during our assessment of patients for cataract surgery. In this case it appears this was life-saving. Other patients in which to strongly consider visual fields testing as routine may include:

Figure 2. Dolman’s test referred to as the ‘hole in the card’ test. The subject views a distant object through the hole with both eyes open. The observer then alternates, closing each eye to determine which is actually viewing the object.8

Figure 3. Visual fields showing bilateral central scotomata.

• Those with diagnosed glaucoma,

• Any patient in which the symptoms don’t match the clinical signs,

• Suspicious discs that may indicate non-glaucomatous etiology, and

• A history of any neurological disorder or previous neurosurgery.

Case Four: Ocular Motility

Patrick* is a 55-year-old-male who was referred for bilateral posterior subcapsular cataracts due to steroid use. He was most symptomatic of glare, especially when driving. He denied any diplopia or polyopia.

Examination revealed visual acuity of: R 6/15, L 6/18. In keeping with his visual acuity, his left cataract was slightly more advanced. The rest of his anterior and posterior segment examination was unremarkable. However, a cursory assessment of his ocular motility revealed signs in keeping with a bilateral Duane’s Type 1 syndrome (Figure 4). On questioning, Patrick did recall being told that he had ‘abnormal eye movements’ as a child. However, since his vision was unaffected, he had never experienced diplopia, and it was cosmetically unnoticeable, so it had been largely ignored.

This raises an important point in that we perhaps should consider an ocular motility examination as a routine part of the assessment for patients presenting for cataract surgery. The main concern being that diplopia is an infrequent but distressing adverse outcome after uncomplicated cataract surgery.

Commonly this is more likely to occur in patients with horizontal strabismus due to a decompensated heterophoria, pre-existing heterotropia or, as in Patrick’s case, a congenital strabismus such as Duane’s syndrome.4,5

Even a simple assessment of ocular motility using the ‘double H pattern’ technique would allow identification of abnormal motility prompting further investigation. In many cases this would assist with counselling the patient in terms of IOL choice (EDOF and trifocal IOLs are best avoided), the possibility of post-operative diplopia that may require prism correction in glasses, or even surgical intervention.

TIMING OF REFERRAL

Assessing patients for cataract surgery involves an individualised approach beyond measuring visual acuity and performing a slit-lamp examination. We first need to understand how a patient uses their vision in their daily life. It is important to spend time taking a history with open-ended questions to determine:

• What are your patient’s specific visual requirements (for example, are they a night shift worker? Do they drive a lot and when? Is reading as important as distance tasks?)

• What other aspects of their vision are currently affected? (Colour? Contrast? Glare sensitivity?)

• What is their understanding of their vision problems?

• If we could offer a solution, what do they think this might look like?

• What is their understanding of visual compromise?

Many of these questions have been standardised and exist in a variety of versions including in the Catquest 9SF questionnaire. It is possible to adopt them into your own personalised questionnaire for patients to complete prior to seeing you.6

Apart from taking a history, a decision on timing of referral is also dependent on:

• Grading of the severity of the cataract, and

• Establishing if there are other ocular comorbidities (particularly retinal disease, such as diabetic retinopathy and/or maculopathy, and untreated glaucoma etc.) If other ocular co-morbidities exist, a stepwise approach needs to be adopted to optimise surgical outcomes.

There is nothing wrong with referring a patient to an ophthalmologist early to begin a conversation about expectations of cataract surgery and achievable outcomes. Research has shown that patients are more likely to have reasonable expectations and be happy with their post operative outcome if they understand the process and become invested in the options put forward.7

CONCLUSION

You may notice a ‘theme’ emerging from this PreView protocol and that is that the focus appears to be on neuro-ophthalmology. This is an important point and emphasises that the visual processing of the entire anterior visual pathway (from pupil to optic nerve, to retina, to brain) needs to be intact if we are to obtain excellent refractive outcomes following cataract surgery. Perhaps you will use the protocol as it is, or modify it to suit your needs. In any case, the key take-home message here is to practise this protocol as per routine.

“ This brings us to the question of whether a visual fields test should be routine during our assessment of patients for cataract surgery ”

Figure 4. Ocular motility examination demonstrating bilateral Duane’s Type 1 syndrome. A) Impaired abduction of left eye on left gaze; B) Small left esotropia on primary gaze; C) Impaired abduction of right eye on right gaze.

Although it is likely to reveal anomalies in only a small number of cases, utilising a protocol like this will ensure that you perform a thorough clinical assessment of all patients presenting for cataract surgery.

*Names changed to protect patient privacy.

To earn your CPD hours from this article, visit: mieducation.com/improving-cataract-outcomesfrom-the-start.

Dr Christolyn Raj MBBS(Hons) MMED MPH FRANZCO is a Melbourne-based ophthalmologist. One of her subspecialty areas is cataracts and laser-assisted cataract surgery.

Dr Raj is a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists and the American Association of Ophthalmologists.

In addition to practising privately, she holds appointments at The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne and Epworth Freemasons Hospital.

She is currently undertaking clinical research projects in affiliation with her retinal clinics at the University of Melbourne, in surgical management of patients presenting with cataract in the context of diabetic eye disease.

References

1. Al-Zubidi, N., (ed.), Adie Pupil, American Academy of Ophthalmology EyeWiki, available at: eyewiki.org/Adie_ Pupil [updated 4 Oct 2023, accessed 7 Nov 2023].

2. Cooper, T., Neuro-ophthalmology question of the week: Dilated pupil constricts to pilocarpine 0.125%, Stanford School of Medicine, 8 Feb 2017.

3. Cheng, C.Y., et al., Association of ocular dominance and anisometric myopia, Invest Ophthalmology & Vis Sc 45 (8):2856–60, 2004.

4 Nayak, H., Kersey, J., Oystreck, D. et al. Diplopia following cataract surgery: a review of 150 patients. Eye 22, 1057–1064 (2008).

5 Gunton, K.B., Armstrong, B., Diplopia in adult patients following cataract extraction and refractive surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010 Sep;21(5):341–4.

6. Lundström, M., Pesudovs, K., Catquest-9SF patient outcomes questionnaire: nine-item short-form Raschscaled revision of the Catquest questionnaire. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009 Mar;35(3):504–13.

7. Ye, G., Liu, Y., et al., A decision aid to facilitate informed choices among cataract patients: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Jun;104(6):1295–1303.

8. midtownvision.com/blog-posts/find-your-dominanteye, 2019.