mieducation

Success with Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lenses

Presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses (PCIOLs) are increasingly being used in Australia and New Zealand. 1 Our patients are often aware of friends and family who have had cataract surgery and, as a result, are significantly less dependent on glasses for many of their daily tasks. There is an expectation that this outcome is what the majority of people undergoing cataract surgery will experience, and that the majority of patients are likely to prefer this outcome.2

WRITER Susan Gaskell

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand how PROMs differ from clinical measures,

2. Understand the importance of expectation management, patient selection, and strict assessment processes,

3. Recognise how PCIOLs can improve quality of life regardless of age,

4. Appreciate that the final visual outcome may not align with traditional clinical measures of ‘success’.

Market research, undertaken by Kantar on behalf of Alcon in 2019, found that 90% of people in the study would choose either the visual outcome delivered by PanOptix (diffractive trifocal – clear vision at distance, intermediate and near with some glare and halo)3 or Vivity (Wavefront shaping EDOF [extended depth of field] – excellent distance and intermediate vision, functional near,4 and glare halo profile comparable with Acrysof IQ monofocal IOL).5 Interestingly, the proportion of survey participants who preferred the outcome delivered by PanOptix was 51% of the cohort who wanted a PCIOL outcome.2

Obviously, not everyone who wants a diffractive trifocal IOL is going to be suitable, but this research demonstrates that many people are prepared to embrace some compromise to experience the visual and lifestyle advantages of PCIOLs in the same way that many people do when they wear multifocal spectacles or contact lenses. Optometrists approach prescribing and dispensing multifocal glasses and contact lenses by explaining what the lenses can and cannot deliver, matching these characteristics to the patients’ needs and aligning expectations. With this strategy, we have a pretty good chance of landing on a solution that suits our patients’ needs.

Similarly, matching the profile of a PCIOL to the needs of a patient and actively managing expectations around the visual outcome is the best first step to choosing an IOL that will provide our patient with a successful outcome.

THE DEFINITION OF SUCCESS

We’ve all heard the phrase ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, meaning that the one who ‘beholds’, or sees, is the one who decides what is beautiful and what is not. Similarly, the definition of ‘success’ in relation to cataract surgery can depend on who you ask. Traditionally, when surgeons and optometrists assess the success of cataract surgery, we like to see good visual acuities, a quiet white eye, a clear cornea, a round pupil, a well-centred IOL and in the age of technology, an emmetropic refractive outcome. These clinical measures are easily assessed and recorded and don’t require much input from our patients. A patient may define success by a completely different set of measures. For example, the patient who by all clinical measures has had a brilliant outcome, but still needs to wear glasses for all but distance vision, may be quite disappointed by the outcome and consider it a failure because they didn’t expect to need glasses after surgery. Conversely, a previously hyperopic patient, who has had a mild myopic refractive outcome, might be thrilled because their unaided vision at all distances is significantly better than prior to surgery, even though the emmetropic refractive target was not met.

The medical fraternity, as a whole, is becoming more interested in understanding these patient-centric measures of success, and the terminology used is Patient Reported Outcomes Measures, or PROMs. PROMs can help clinicians understand the potential benefits of a treatment beyond the clinical measures, as they address the impact of a surgical outcome on a more holistic/quality of life basis. Consider this example:

A patient in her 70s, who recently lost her husband, wears multifocal glasses. He used to help her watch for uneven ground because she felt unsteady when walking wearing her multifocal specs. Now that she does not have his help, she is not leaving the house as much as she used to. This means she is not getting as much exercise, and she is not having as many social interactions.

She visits her optometrist and discovers that she requires cataract surgery. She is advised that she could have monofocal IOLs and continue to wear multifocal spectacles, or she could have PCIOLs and be more independent of spectacles.

Figure 1a: AcrySof IQ Vivity® IOL,

Figure 1b: Trifocal IOLs Acrysof IQ PanOptix.7

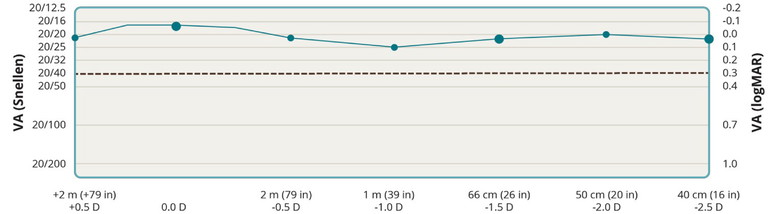

Figure 2. PanOptix Defocus Curve.3

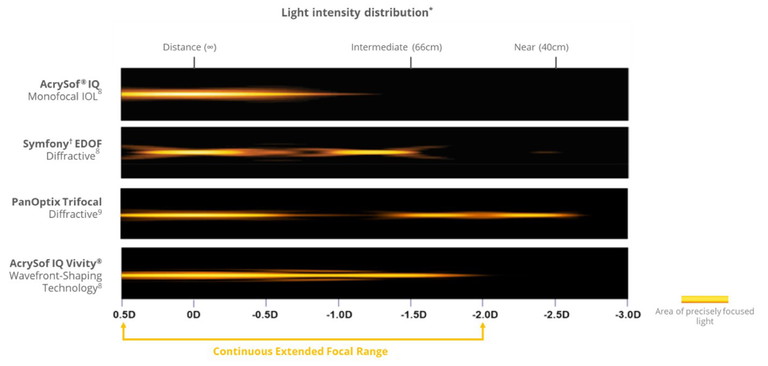

Figure 3. Light intensity distribution.8,9*Simulated photopic through-focus point spread function (light intensity [energy]) – polychromatic.

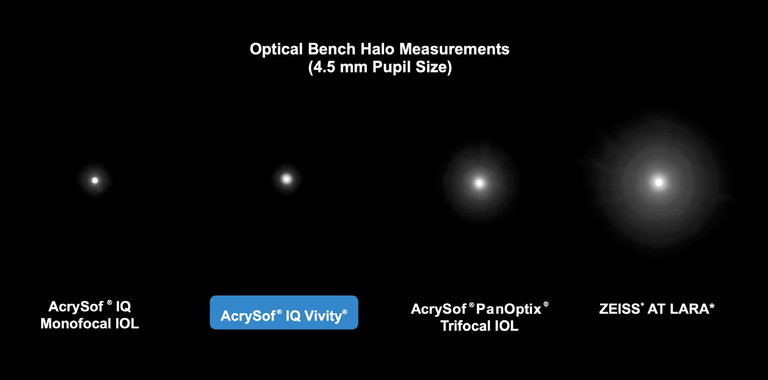

Figure 4. Bench halo test.10

If she were to have a refractive outcome that enabled her to see comfortably at distance and intermediate without the need for multifocal spectacles, she might feel more confident of her footing when walking.6 This may help her to regain independence, maintain mobility, and increase her social interactions – all of which improve her quality of life and mean she is much more likely to live better, for longer. These more holistic outcomes are not measurable with clinical measures of surgical success.

Optometrists informally assess patientreported outcomes daily and incorporate them into patient management. For example, a patient with 6/9 vision who doesn’t drive and is happy with their vision may not require referral for cataract, whereas a patient with better visual acuity but significant glare that affects their confidence while driving, may.

The challenge is, how can researchers assess patient-reported outcomes more consistently so that findings can be reported in a scientific manner, given that they are much more subjective than clinical measures?

One of the current solutions is the use of validated questionnaires. A validated questionnaire is one that has been assessed to confirm that it measures what it sets out to in a consistent manner that can be applied across a variety of settings.

These questionnaires usually ask a combination of global questions such as, “How satisfied are you with your vision overall?”. Additionally, they ask more taskbased questions such as “How satisfied are you with your vision for driving?”.

The patient selects from options ranging from “very satisfied” to “very unsatisfied”, with the goal being to assess how they are managing and how happy they are with their vision.

PROMs are ideally performed before and after surgery to measure the impact on the patient’s quality of life. PROMs can also look at quality of vision from a patient’s perspective and are useful for measuring success with lenses, such as trifocal IOLs where visual acuity alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Quality of vision (such as the impact of glare and halos) and quality of life (such as the impact of reduced spectacle independence) both need to be taken into account when determining whether the surgical intervention has been a success.

TRIFOCAL IOLS AND PATIENT SATISFACTION

Alcon introduced its diffractive trifocal IOL PanOptix to Australia and New Zealand in 2017. It delivers clear vision at distance, intermediate and near, with a continuous near to intermediate range of vision from 40cm to 80cm, and an intermediate focal point at 60cm 7(Figures 1 and 3). The clinical data (defocus curve, Figure 2), light intensity distribution (Figure 3), and bench halo test (Figure 4), indicated that the lens delivered the focal range with less dysphotopsia than other diffractive IOL designs. However, that clinical data didn’t answer the question of how satisfied patients were with the outcome of their surgery, i.e. patient-reported outcomes. Alcon wanted to be sure that patients were as happy with their outcomes as the clinical data suggested they would be, so set out to investigate patientreported outcomes with PanOptix.

“ The research findings indicated a very low incidence of bothersome visual dysphotopsias ”

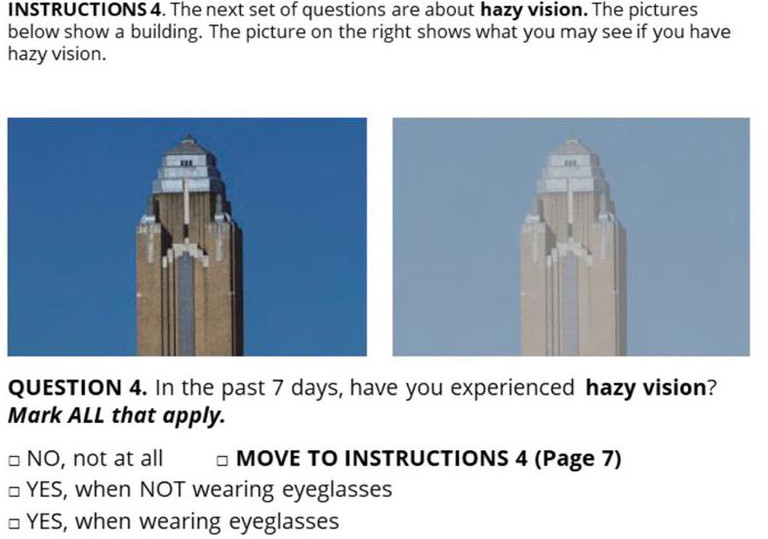

To do this, Alcon developed a validated questionnaire to assess (a) what dysphotopsias patients with PanOptix noticed, (b) how often they noticed them, (c) how significant they were, and (d) how bothersome they were. Figure 5 presents an example of a question in the survey.

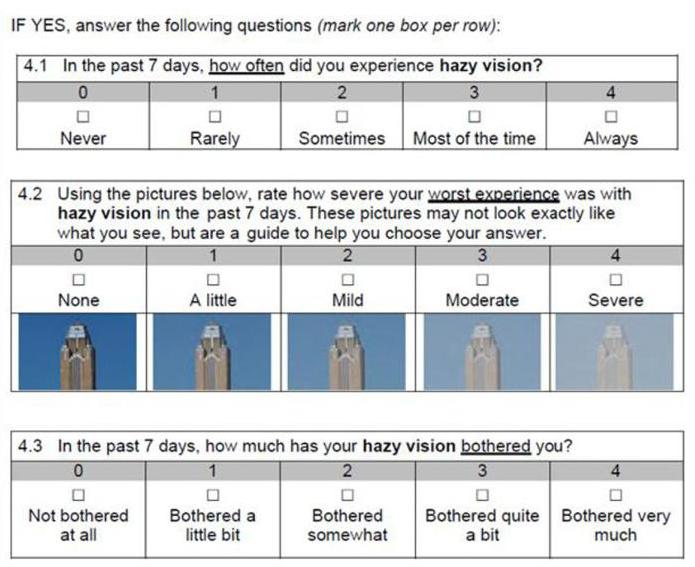

Finally, to get an overall indication of how satisfied patients were with their visual outcome, participants were asked whether (a) they would get the same IOL again and (b) whether they would recommend it to a friend.

The research findings indicated a very low incidence of bothersome visual dysphotopsias. Most of the patients who found they were very bothered by glare, halo or starbursts were still satisfied overall with the benefits the lens offered. Indeed, 99.2% of study participants would have the same lens again (Figure 6).

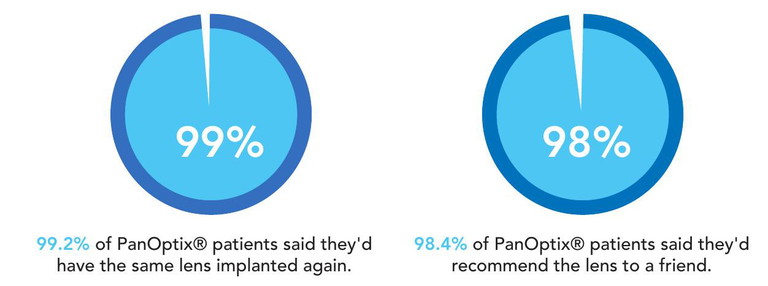

An Australian paper by Ison, Scott, and Apel took this a step further. They compared patients’ assessment of dysphotopsias prior to cataract surgery with their assessment of the same dysphotopsias three months following implantation with PanOptix IOLs. Their results indicated that although patients noticed dysphotopsias, they were not necessarily bothered by them. Additionally, they demonstrated that many patients had been more bothered by dysphotopsias prior to cataract surgery and diffractive trifocal implantation than after, particularly their impact on night driving (Figure 7).13

What these studies make clear is that not everything a patient notices is bothersome, and not everything that bothers them outweighs the benefits that they perceive. Most patients who have been implanted with PanOptix trifocal IOLs are not bothered by glare and halo. Of those who are, most would still choose to keep the diffractive IOL because of the benefits spectacle independence brings to their quality of life.

For these patients, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Even though their vision isn’t ‘perfect’, their definition of success was spectacle independence, not visual perfection. Ison, Scott, and Apel found that 90% of patients in their study were willing to accept greater perception of halo and glare to be able to see without spectacles.13

SETTING AND MATCHING EXPECTATIONS

It is worth noting that multifocal spectacle lenses are imperfect optical devices, but when properly managed, achieve overwhelmingly successful outcomes. Multifocal spectacle lenses provide clear vision at a variety of distances, but to obtain that, there are visual disturbances that occur when the wearer uses parts of the lens that are outside the reading corridor. Optometrists regularly, if not routinely, counsel patients about this and the adaptation that will be required.

They identify patients for whom multifocal spectacles are not ideal and prescribe and dispense accordingly. The vast majority of patients adapt well and use the lenses with no difficulties. Some, often for occupational reasons, find that multifocal glasses are not always ideal, however they continue to use them because of the convenience of only needing one pair of glasses. The optometrist has set and matched patient expectations to the type of spectacle lens dispensed.

There is no direct correlation between adaptation to multifocal spectacles and trifocal IOLs. However, the approach to embracing the benefits of trifocal IOLs, with the understanding that they may not provide perfect vision in every circumstance, is similar to the conversation that is had regarding multifocal spectacle lenses. When the optical corrective appliance behaves as the patient expects, they are reassured and more prepared for the adaptation process. When the immediate result is unexpected by the patient, even though it is what is clinically expected, the patient is much more likely to view this unexpected outcome as a negative experience. This is why extensive patient counselling to align expectations prior to cataract surgery with PCIOLs is so important.

Figure 5. Extract from Quality of Visual Disturbance Questionnaire: A Validated IOLSAT Questionnaire.11

Figure 6. In a clinical study, 129 patients were asked about their experience with the PanOptix lens.12

Figure 7. Patient expectation, satisfaction and clinical outcomes with a new multifocal intraocular lens.13

PATIENT SELECTION

Historically, the stereotypical PCIOL patient has been younger, healthy, and physically active. They have had high expectations and have been strongly motivated to obtain good vision at all distances. They have also been relaxed enough to adapt to the dysphotopsias (such as halo, glare and starbursts) that come, along with the multiple focal points that trifocal IOLs deliver. Patients who were older, less mobile and less motivated for spectacle independence were typically assumed to be less suitable for PCIOLs. It was often assumed they had less to gain from spectacle independence. However, a practitioner would do well to keep in mind that PCIOLs can offer significant quality of life advantages to patients who may not appear to be the ‘ideal’ trifocal IOL candidate.

A significant factor to consider with our older patients is their risk of falls. Multifocal spectacles are a well-established contributor to falls,14 and the implications of our patients having a fall are often more far-reaching than simply having to repair or replace a pair of spectacles. Risk factors for falls are many. The biggest is having had a previous fall, but multifocal spectacles are estimated to contribute to between 35% and 50% of falls inside and outside the home respectively. 15 The outcomes of an individual having a fall are also varied. Worst case scenario is that the individual sustains a fatal injury, closely followed by those who sustain an injury that renders them hospitalised or immobile. It is widely accepted that individuals who experience a hip fracture have a higher mortality rate than those who do not in the years following the injury. What is less obvious than these sobering statistics is the number of people who lose confidence, become less active because of their fear of another fall, go out less, and have fewer social interactions as a result. These people are likely to lose mobility and cognitive function faster than they would have, had they maintained their confidence and continued to be physically and socially active. 16

There may be patients for whom the apparent disadvantages of a diffractive trifocal may be outweighed by other potential benefits, such as a person who has postural issues, or who uses a wheelchair or a walker.

Multifocal spectacle lenses are designed in such a way that they work well for most of the population who, by definition, are of average height, have ‘normal’ posture, a full range of head and eye movement, and spend their days in an upright position, looking straight ahead. An individual who is physically outside these norms may experience difficulty using multifocal glasses. Trifocal IOLs will give them comfortable, functional vision at distance, intermediate, and near regardless of their posture or head position.

Or consider a person who lives in aged care, perhaps with dementia.17 I’m sure we’re all aware of how frequently a resident's glasses can be misplaced in care facilities. If a resident has functional vision at distance, intermediate, and near without the need for glasses, their quality of life is likely to be better because they will still be able to see the things that bring some interest and meaning to their lives – recognising faces and facial expressions, participating in mentally stimulating activities (reading, looking at photos, playing games), appreciating and recognising food, even the ability to shave or apply makeup. For a patient in a situation such as this, it may be more beneficial overall for them to have a PCIOL, even in the presence of other ocular disease. This is because they are likely to have more functional vision at every distance (even though compromised) than they would with a monofocal IOL, which is still going to deliver compromised vision due to other ocular health issues, but only has one focal distance.

“ the definition of ‘success’ in relation to cataract surgery can depend on who you ask ”

THE OPTOMETRIST’S ROLE

Optometrists are not responsible for IOL choice, and nor should we be. However, as primary eye health practitioners, we are the first step in a patient’s journey through the process of cataract surgery. Our patients are exposed to information about healthcare and treatment options through a variety of sources, from conversations with taxi drivers, to Tik-Tok and on the rare occasion, clinical papers. They may have drawn conclusions and set their own expectations about cataract surgery outcomes from any number of sources, which may or may not be reputable or accurate. Unless they’ve spoken to an eye health practitioner, those conclusions and expectations won’t be specific to that patient’s individual circumstances.

Optometrists are well situated to discuss realistic expectations and potential benefits of PCIOLs with their patients. If time does not allow, we can refer patients to a surgical practice that takes the time to understand the patient’s visual and lifestyle needs, and counsels patients appropriately. At the very least, when leaving their optometrist, patients ought to understand that PCIOLs provide significant benefits but may not be suitable for everyone. They will need to discuss this further with the ophthalmologist.

Cataract surgery is increasingly becoming both a treatment for an ocular condition and for the pursuit of refractive improvement. Just like other ophthalmic sub-specialties, such as glaucoma or surgical retina, cataract refractive surgery has become a subspecialty, often focussing on providing patients with presbyopia correcting options where appropriate. As with any patient management decision, involving a surgeon with a demonstrated expertise in the use of PCIOLs in the care of your patients is likely to improve the chances of a satisfactory visual outcome.

IMPORTANCE OF THE OCULAR SURFACE

Repeatable accurate biometry readings are essential to achieve targeted refractive outcomes from PCIOLs and trifocal IOLs in particular.

To acquire an accurate biometry reading we need a stable tear film and a healthy ocular surface.

This is because a poor tear film and poor ocular surface will result in scans that are distorted, and data that is variable and therefore unreliable. The use of artificial tears immediately prior to scans is not a satisfactory solution as excess fluid on the ocular surface introduces its own set of inconsistencies.18

Consequently, the best solution is proactive management of the ocular surface in the weeks leading up to biometry measurements. Ophthalmology practices that use trifocal IOLs will often delay final biometry and treat dry eye until they are satisfied that they have quality data to base IOL power selection on.

Elderly patients often prefer to have a family member attend specialist appointments with them and may also require transport. Coordinating this can be time-consuming and stressful. This can be avoided if the referring optometrist pro-actively manages any dry eye in advance.

PCIOL ADAPTATION

An experience that is almost universal after cataract surgery, regardless of the IOL that is implanted, is surgically induced dry eye.18 Dry eye and tear film instability cause discomfort, periods of excessive tearing and fluctuating vision.19 These symptoms bother many patients and may require management over weeks or months post-surgery before symptoms resolve. Patients with PCIOLs are likely to be more bothered by periods of blurred vision due to post-surgical dry eye than their counterparts who received monofocal IOLs because of the more complicated optics of a PCIOL.17 Some patients, even those with monofocal IOLs, will interpret these symptoms as indications that something has gone wrong with their surgery. It is important to reassure these patients that what they are experiencing is a normal, short-term effect of the surgery and is easily managed by continuing to use ocular lubricants regularly during the day.

It might surprise you to learn that the primary reason for dissatisfaction with trifocal IOLs is not due to glare and haloes that are inherent to diffractive IOLs, but rather to residual refractive error.20 Despite every effort to obtain accurate biometry and use appropriate IOL calculation formulae, the refractive outcome is not always exactly what was aimed for.

If a patient is to be implanted with a monofocal IOL, and expects to continue to wear glasses after surgery, a small residual refractive error can be easily accepted and compensated for with the inevitable spectacle prescription.

In the case of a patient being implanted with trifocal IOLs, a small residual refractive error may be more problematic for a few reasons: firstly, the simple effect of ametropia.

A hyperopic result will mean that the patient may not see as clearly as they would like in the distance and for reading.

A myopic result will mean that distance vision is less clear, but near and intermediate vision may still be acceptable.

An astigmatic result in a patient with trifocal IOLs is likely to be much more visually disturbing at all distances than might be expected when compared with the same refractive error in a patient with monofocal IOLs. Secondly, the impact of blur from uncorrected refractive error is additional to the impact of the complex optics of a PCIOL. For this reason astigmatism, in particular, is more problematic. The starbursts associated with astigmatism, added to the dysphotopsias inherent in PCIOLs, may cause the resultant dysphotopsias to be more noticeable than either contributor on their own.

It is important that surgeons discuss the possibility of residual refractive error with patients before surgery. This will ensure patients understand that further procedures, such as refractive laser or a piggyback IOL, might be required to reach an emmetropic outcome. Depending on the amount of residual refractive error and the patients’ needs and expectations, they may elect to wear glasses if further clarity is required, or they may find that, regardless of any residual refractive error they have comfortable, functional vision and do not wish to have any further intervention.

Neuroadaptation is a factor that is at play in the weeks and months following cataract surgery. It is well accepted that this occurs, but it is difficult to measure, or to predict a timeframe.

Optometrists often notice the effect of neuroadaptation when observing patients adapting to changes in spectacle prescription or lens design. Some people seem to be fine from the first moment, whereas others require much more time and support until they feel comfortable with their new glasses. There are personality traits that indicate patients who may take longer to adapt or be less amenable to visual imperfections.21It is helpful to indicate any of these observed traits in a patient’s history when referring them for cataract surgery.

As with spectacle adaptation, surgeons report that some patients will be very comfortable with their vision immediately after PCIOL implantation; many will notice improvement over three to six months, and very occasionally it can take 12 to 18 months for them to reach the point where they feel comfortable with the range and quality of vision they obtain with their PCIOLs.22

“ To acquire an accurate biometry reading we need a stable tear film and a healthy ocular surface ”

TIPS FOR HELPING PATIENTS ADAPT

While patients are adapting to their new way of seeing the world there are a few things that an optometrist can do to reassure and support them:

• Check for posterior capsular opacification (PCO). Small degrees of PCO on a PCIOL can be surprisingly detrimental to vision.17 Referral for YAG capsulotomy may be necessary if visual acuity is impacted by PCO.

• Check ocular health. If vision is not as good as expected, it is important to rule out all possible causes, including retinal problems.

• Manage any dry eye.

• Check carefully for residual refractive error. PCIOLs can be tricky to refract. Their complex optics will be difficult for auto-refractors to assess, so auto-refractor results may be inaccurate. Duochrome will be unreliable for the same reason. The best way to refract is to aim for maximum plus/least minus that gives best distance visual acuity. Patients with a hyperopic or astigmatic refractive outcome should see an improvement in their vision at all distances when the refractive error is corrected with an appropriate single vision lens. Patients with a myopic outcome are likely to be seeing well at intermediate and near without assistance. Correction of the myopic refractive error will improve their distance acuity and the available working distance but may not have a large subjective impact on their near acuity.

• Encourage use of extra lighting, especially when reading. When someone with a natural crystalline lens or a monofocal IOL is looking at an object (with appropriate corrective lenses) all of the light entering the eye from that object is focussing on the macula. A diffractive IOL splits that light into two or three focal points, so the reduction in the amount of light that is in focus on the macula in low light conditions may be enough to cause a patient to feel that their vision is less clear. Adding extra illumination is likely to help with this.

• Remind the patient that their brain needs to get used to seeing the world a bit differently. The IOLs they have are good, but they’ll never do the job as well as the original parts – just as a knee or hip replacement restores function to a joint, it doesn’t work in the same way as the original, and it takes time and effort to get used to the replacement part. Continue to monitor the ocular surface to ensure that dry eye doesn’t unnecessarily complicate the neuroadaptation process.

• Reiterate what can be expected from the IOL. Alcon Vivity IOLs provide excellent unaided vision from distance through to arm’s length, and it is expected that lowadd glasses will be required for fine detail or extended periods of close work. Alcon PanOptix IOLs are designed to provide excellent vision for distance, intermediate and near (40cm–80cm),7 however, if a patient wants to undertake tasks at 30cm, they either need to adjust their working distance, or use low-add glasses to see clearly at 30cm. They are also designed to work best with binocular summation, so dissuading your patient from comparing one eye with the other (just as we do with multifocal contact lens and spectacle wearers) will be very helpful.

• Normalise awareness of dysphotopsias. All diffractive PCIOLs will cause a degree of visual disturbance because they are splitting light into more than one focal point. Alcon Vivity EDOF IOLs provide a presbyopiacorrecting option with a monofocal-like glare and halo profile.11 However, any patient who wants to read fine detail at near, comfortably without glasses, will need to use a trifocal IOL and all trifocal IOLs are diffractive. The presence of haloes indicates that the IOL is doing its job. When the lenses are newly implanted, the patient will be very aware of the differences in their vision when compared with their vision before surgery. As time goes by, they become less aware and less bothered by the dysphotopsias noticed in the first few days and weeks following surgery. Ideally, this would have been discussed with the patient before surgery.

• If your patient feels they are not obtaining any benefit from their PCIOLs, demonstrate what they see at different distances – have the patient read the distance chart binocularly, then a reading chart at arm’s length and at a comfortable reading distance. Then put –2.50D in a trial frame (or –1.50 if they have EDOF IOLs) and ask them to do the same thing wearing the lenses to demonstrate what their vision would be like with monofocal IOLs.

• If you or your patient still have doubts about the suitability of an IOL design that a patient has had implanted, detail the concerns in a letter to the surgeon who implanted the IOLs. It isn’t helpful for the patient, or the surgeon, to have an optometrist say something like “I wouldn’t have chosen that lens design for you”. To obtain a positive outcome for the patient, cooperation and clear, timely communication between all parties is essential.

Susan Gaskell is Professional Development Manager for Alcon Surgical ANZ. She seeks to improve patient outcomes following cataract surgery by providing optometrists with information about Alcon’s IOL technology and by building stronger, more effective communication between optometrists and ophthalmologists. Ms Gaskell brings to this role many years of clinical optometry experience in both private and corporate practice, as an employee and franchise owner.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit: mieducation.com/success-with-presbyopiacorrecting-intraocular-lenses.

This article is sponsored by Alcon Laboratories Pty Ltd: (AUS)1800 224 153 or (NZ) 0800 101 106. ANZ-ACP- 2300001.

References

1. Alcon Data on File 2021. ANZ PCIOL Market Penetration Data – MarketScope.

2. Kantar Consumer Cataract Awareness Research July 2021 (Full Report).

3. Modi, S., Lehmann, R., Maxwell, A., Solomon, et. al., (2021). Visual and patient-reported outcomes of a diffractive trifocal intraocular lens compared with those of a monofocal intraocular lens. Ophthalmology, 128(2), 197–207.

4. Alcon Data on File, TDOC-0055575. 9 Apr 2019, 5.

5. Bala, C., Poyales, F., Guarro, M., et al. (2022). Multicountry clinical outcomes of a new nondiffractive presbyopiacorrecting IOL. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 48(2), 136–143.

6. Hall, C.D., Barnes, C.S., Gutherie, A.H., & Lynch, M.G. (2022). Visual function and mobility after multifocal versus monofocal intraocular lens implantation. Clinical & Experimental Optometry, 105(1), 70–76

7. Alcon internal technical report: TDOC- 0018723. Effective date 19 Dec 2014.

8. Alcon Data on File, TDOC-0056392. 18 Jun 2019.

9. Alcon Data on File, TDOC-0056797.

10. Alcon Data on File. Optical Evaluations of Alcon Vivity, Symfony, and Zeiss AT LARA* IOLs Bench study.

11. Alcon Data on File 2019: US Vivity clinical study summary TDOC-0055576.

12. AcrySof PanOptixTM Directions for Use TDOC-0055352.

13. Ison, M., Scott, J., Apel, J., & Apel, A., (2021). Patient expectation, satisfaction and clinical outcomes with a new multifocal intraocular lens. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 15, 4131–4140.

14. Lord, S.R., Smith, S.T., & Menant, J.C. (2010). Vision and falls in older people: risk factors and intervention strategies. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 26(4), 569–581.

15. Lord, S.R., Dayhew, J., & Howland, A. (2002). Multifocal glasses impair edge-contrast sensitivity and depth perception and increase the risk of falls in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(11), 1760–1766.

16. Rubenstein, L.Z., & Josephson, K.R. (2002). The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 18(2), 141–158.

17. Braga-Mele, R., Chang, D., Dewey, S., et al., & ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee (2014). Multifocal intraocular lenses: relative indications and contraindications for implantation. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 40(2), 313–322.

18. Favuzza, E., Cennamo, M., Vicchio, L., et al., (2020). Protecting the ocular surface in cataract surgery: The efficacy of the perioperative use of a hydroxypropyl guar and hyaluronic acid ophthalmic solution. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 14,1769–1775.

19. Morthen, M.K., Magno, M.S., Utheim, T.P., et al., (2021). The physical and mental burden of dry eye disease: A large population-based study investigating the relationship with health-related quality of life and its determinants. The Ocular Surface, 21, 107–117.

20. Gibbons, A., Ali, T.K., Waren, D.P., & Donaldson, K.E. (2016). Causes and correction of dissatisfaction after implantation of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 10, 1965–1970.

21. Henderson, B., Sharif, Z. & Geneva, I., (2015). Presbyopia Correcting IOLs: Patient Selection and Satisfaction.

22. Pepose J.S. (2008). Maximizing satisfaction with presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses: the missing links. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 146(5), 641–648.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients are more aware than ever before of the potential visual outcomes and reduced spectacle dependence possible with cataract surgery. As such, there is an increasing demand for greater spectacle independence following cataract surgery.

2. Clinical outcomes do not tell the whole story about the success of a surgical intervention.

3. Patient-reported outcomes can be more difficult to define than clinical outcomes, but they are worthwhile investigating because they communicate the holistic benefits of a treatment.

4. Patients may be accepting of and adapt to a level of dysphotopsias with PCIOLs because they value the benefits that these IOLs afford them in much the same way that multifocal spectacle wearers accept and adapt to the limitations of multifocal spectacle lenses.

5. When it comes to discussing IOLs and the benefits they offer, it is worth keeping in mind the impact these benefits can have on the quality of life of your elderly patients. Multifocal spectacles are not a benign visual correction. They are a known falls risk, and there is evidence that the use of PCIOLs can reduce the risk of falls in an elderly population. Aside from that, they can be difficult to use if the frame is out of alignment or if your patient has atypical posture; and they are of no use at all if a patient can’t find them.

6. Successful outcomes with PCIOLs are eminently achievable, however they require careful patient selection, good ocular surface management, accurate and reliable biometry, and clear expectation alignment between surgeon and patient.

7. The end goal of referral, IOL choice, and cataract surgery is to ensure your patients have the best quality of life outcome possible. Optometrists can influence this outcome by providing a referral that highlights patient related factors, such as living situation and mobility challenges as well as clinical data. Ensuring patients are educated about, and have the opportunity to explore their suitability for all IOL options with a qualified ophthalmologist, is also advantageous.