mipatient

Corneal Crosslinking Watch Out for Rare Complications

WRITER Jessica Chi

Corneal crosslinking has dramatically changed the management of keratoconus. Continued monitoring over the long term is important due to the potential for delayed complications

CASE REPORT

Angela Voss* was diagnosed with keratoconus at the age of 41 and underwent bilateral corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) three and a half years ago. Due to thin corneas pre-treatment, hypotonic riboflavin was used to swell the corneas to 400 microns.

She experienced postoperative haze – a common occurrence following CXL – which resolved within a few weeks.

In recent months, Ms Voss noticed a deterioration in her vision and presented reporting increasing difficulty reading her phone. Although spectacles were prescribed two years earlier, she did not wear them as she felt they provided little benefit.

Clinical Findings

Unaided vision: R 6/38-, L 6/120.

Refraction results: R +3.75 /-4.75 × 50 (6/24), L +10.00 /-3.50 × 93 (6/30).

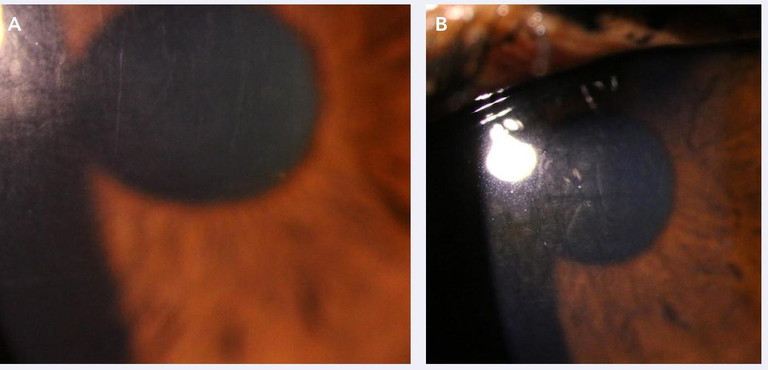

On examination, both eyes showed moderate central corneal haze with prominent stromal striae (Figures 1A and B), as well as corneal stromal and endothelial folds L>R.

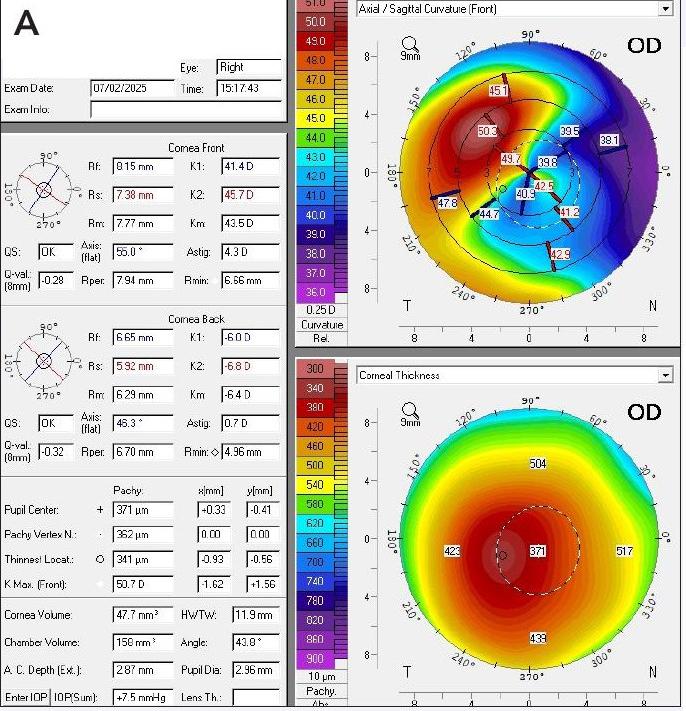

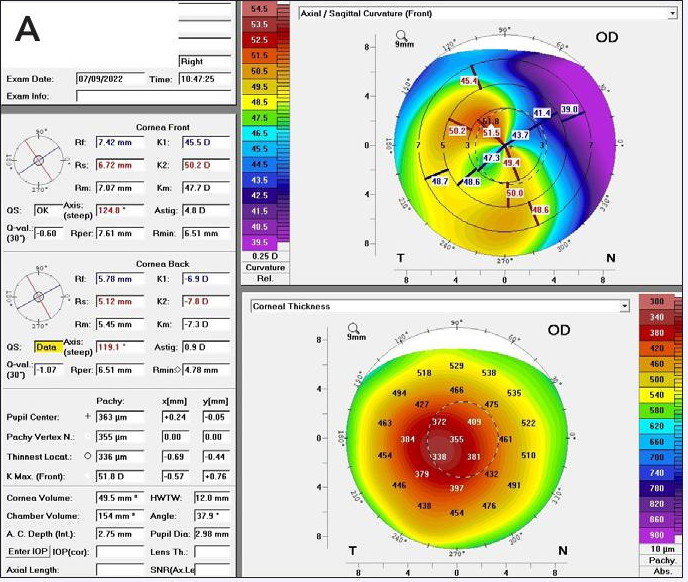

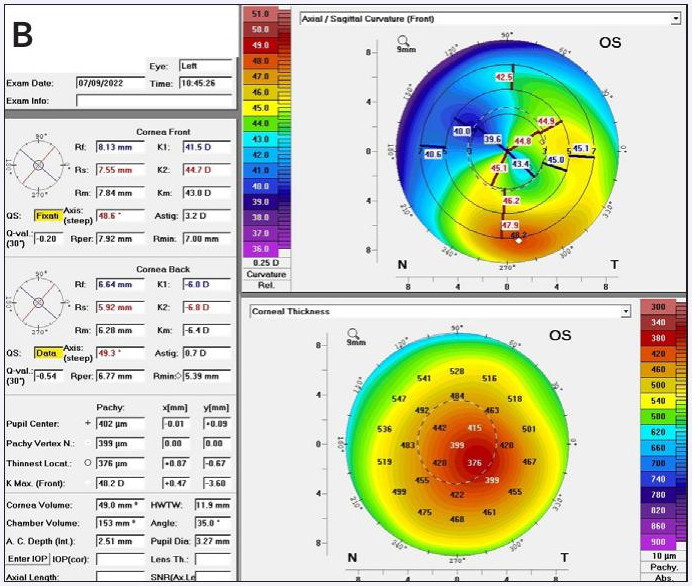

Tomography (Pentacam AXL-Wave) demonstrated inferior corneal flattening, appearing as the opposite of a cone typical of keratoconus.

Kmax values: R 43.4D, L 37.5D (Figures 2A and B). Her central corneal thicknesses (CCT) were R 419, L 371 microns.

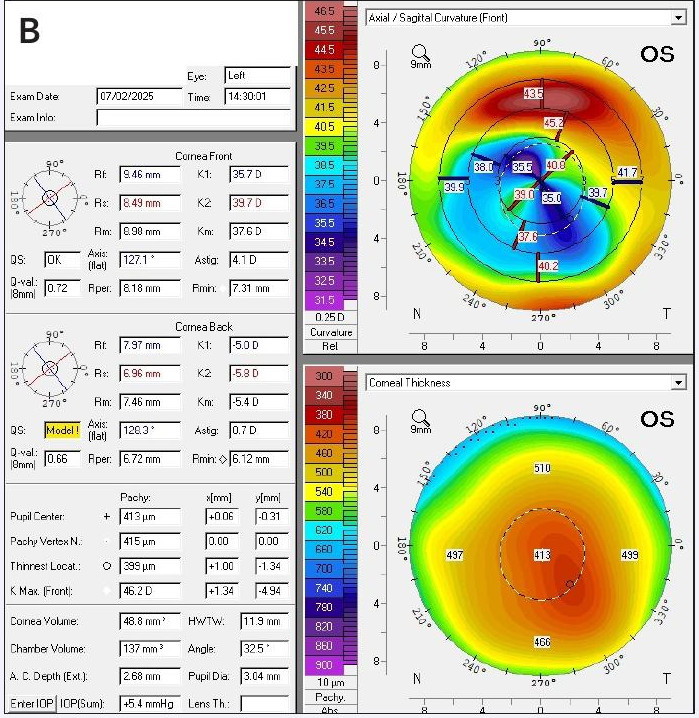

Pre-CXL records obtained from her surgeon: Kmax: R 48.5D, L 44.9D, revealing a 5.1D and 7.4D flattening respectively.

Pre-CXL CCT: R 339 microns, L 374 microns.

At her nine-month post-CXL follow-up, Ms Voss’ Kmax had reduced to R 47.7D, L 43.0D (Figures 3A and B). This represented a flattening of 0.8D in the right eye and 1.9D in the left. Her CCTs had also increased to R 363, L 402 microns.

Ms Voss had not been reviewed since that time, but it was evident her corneas had continued to flatten and thicken, particularly in the left eye.

After presentation, she was fitted with scleral lenses and achieved contact lens acuities of 6/9 in both eyes. For now, she will continue to be monitored without further intervention.

DISCUSSION

Corneal collagen crosslinking was first shown to effectively halt the progression of keratoconus in 2003,1 and since then has become the standard treatment for progressive cases. The original ‘Dresden protocol’ involves saturating the corneal stroma with riboflavin, followed by 30 minutes of ultraviolet-A (UV-A) irradiation. This creates covalent bonds – or ‘crosslinks’ – between collagen fibres, enhancing stromal rigidity.

Due to the large size of its molecules, riboflavin does not penetrate an intact epithelium. Therefore, the corneal epithelium is typically debrided to allow effective stromal absorption. Safety studies have confirmed that CXL does not damage the corneal endothelium, provided UV-A exposure is correctly calibrated and corneal thickness exceeds 400 microns. Patients with thinner corneas, like Ms Voss, can still undergo treatment if the cornea is artificially swollen to meet this threshold.1

“While CXL is generally regarded as safe and effective, common transient complications include pain, temporary haze, and epithelial defects”

Figure 1. Imaging showed moderate central corneal haze with prominent stromal striae A) right eye, B) left eye.

Figure 2. Tomography at presentation. A) right eye and B) left eye demonstrated inferior corneal flattening, appearing as the opposite of a cone typical of keratoconus.

Figure 3. Nine-month post-CXL Kmax values for A) right eye and B) left eye.

Keratoconus is characterised by corneal thinning and ectasia, leading to irregular astigmatism and visual distortion. Though previously considered rare, it is now believed to affect up to one in 200 individuals in New Zealand,2 with a global prevalence of approximately 1.38 per 1,000 based on recent meta-analyses.3 If untreated, keratoconus can progress to severe corneal deformation, scarring, and potentially require corneal transplantation.

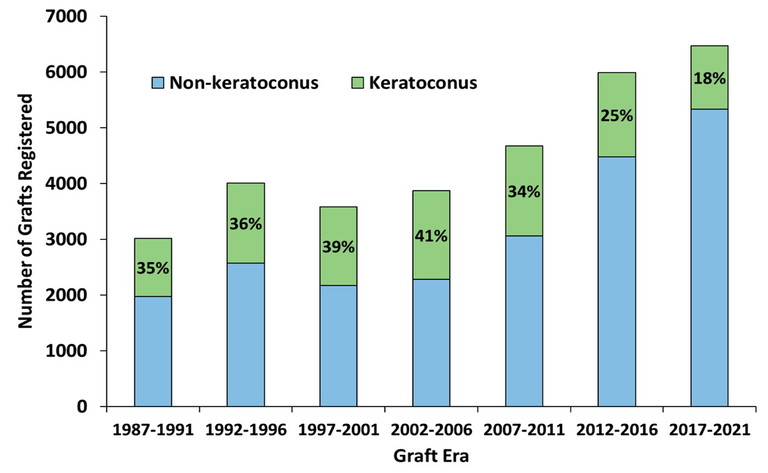

CXL has dramatically changed the management of keratoconus, contributing to a global reduction in corneal transplant rates. In the US, the 2023 Eye Banking Statistical Report shows a steady decline in transplants for corneal ectasia and thinning.4 In Australia, the proportion of grafts performed for keratoconus dropped from 35% (1987–1991) to just 18% (2017–2021) (Figure 4).5

Figure 4. Proportion of grafts performed for keratoconus in Australia.5

“CXL has dramatically changed the management of keratoconus”

While the primary aim of CXL is to stabilise the condition, corneal flattening is a common post-treatment effect. On average, a flattening of two dioptres occurs after one year, increasing to three dioptres after five years.6,7 Typically, this leads to reduced corneal irregularity and improved unaided or spectacle-corrected vision.

However, there are reports of ‘extreme’ flattening, defined as a reduction in Kmax exceeding five dioptres. One study found that 15.5% of patients experienced this outcome, sometimes accompanied by loss of corrected visual acuity.7 Risk factors include central cone location, younger age, and higher baseline Kmax.

Ms Voss’ case resembles a recently reported instance of delayed-onset extreme flattening, Descemet’s folds, and visual decline – nine years post-CXL in a patient treated at age 38.8 It is believed that keratoconus naturally stabilises by the mid-to-late 30s, as endogenous collagen crosslinking increases with age.

Though rare, such cases highlight the importance of long-term follow-up. Other reported complications include extreme thinning, scarring, and persistent haze. While CXL is generally regarded as safe and effective, common transient complications include pain, temporary haze, and epithelial defects. Less frequent but serious risks include infection and sustained stromal haze.

Thus, postoperative monitoring is essential, and treatment should only be reserved for cases with documented progression.

*Patient name changed for anonymity.

Jessica Chi is the Director of Eyetech Optometrists, an independent speciality contact lens practice in Melbourne. She is the current Victorian, and a past National President of the Cornea and Contact Lens Society, and an invited speaker at meetings throughout Australia and beyond. She is a clinical supervisor at the University of Melbourne, a member of Optometry Victoria Optometric Sector Advisory Group, and a Fellow of the Australian College of Optometry, the British Contact Lens Association, and the International Academy of Orthokeratology and Myopia Control.

References available at mivision.com.au.