mifeature

Intraprofessional Collaboration

The Key to Optometry’s Future

Equipped with a comprehensive understanding of the visual system, ocular disease, and the pharmacological management of eye disorders, optometrists in Australia and New Zealand have much to offer. However, the significant level of knowledge, clinical skills and experience contained within the optometry profession ought to be harnessed to its full potential and utilised in a more effective manner. By focussing on developing specialised areas of interest, and embracing opportunities for intraprofessional collaboration, optometrists can improve patient outcomes, promote the development of a more advanced optometric workforce, and aid broader healthcare system efficiencies. Thomas Ford proposes an evidence-based framework – one underpinned by ethical principles and professional virtues – that will encourage optometrists to become more confident and comfortable about referring within the profession.

WRITER Thomas Ford

A CLEAR RATIONALE

Intraprofessional referrals between optometrists – categorised into clinical skills, experience, and technology – are beneficial for optimising patient care and expanding the scope of practice within the field.1 These include:

• Specific clinical skills such as specialty contact lens fitting, paediatric vision, or Civil Aviation Safety Authority assessments,

• Practitioner clinical experience, which is particularly relevant in areas such as myopia control and ocular pathology, and

• Access to clinical technology including optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultra-widefield retinal imaging, visual fields, ocular biometry, corneal topography, among others.

The following scenarios demonstrate instances of effective inter-optometrist referral and the appropriate use of Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item 10905 – referred comprehensive initial consultations – where patients are intraprofessionally referred to receive clinically necessary care.

Scenario 1: Clinical skills

A patient with keratoconus presents following recent bilateral corneal crosslinking. They mention that their corneal surgeon has recommended specialty contact lenses. Given that their best spectacle-corrected visual acuities are 6/15 monocularly, they want to have the freedom to drive without spectacles. Despite possessing the required theoretical knowledge, you do not feel sufficiently skilled to assist this patient in achieving their desired visual outcome. Instead, following discussion, you decide to refer this patient for rigid lens assessment and fitting with a skilled optometrist colleague at a dedicated specialty contact lens clinic.

Scenario 2: Clinical experience

A young myope has continued to demonstrate axial length progression, which exceeds that of their age normative range, despite compliance with Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacle wear. You do not feel comfortable nor appropriately experienced to continue managing this patient given their myopic progression, so you decide to refer to an optometrist colleague who has extensive experience and training in myopia management.

Scenario 3: Clinical technology

An elderly patient presents reporting sudden onset blurry vision, with a family history of macular degeneration. Dilated fundus examination revealed evidence of age-related macular degeneration; however, your clinic does not have access to OCT. As such, you choose to refer this patient to have OCT performed at a nearby optometry clinic to assess for evidence of macular neovascularisation.

INTRAPROFESSIONAL REFERRALS DECLINING

The MBS supports intraprofessional optometric referrals through item 10905 – referred comprehensive initial consultations – which enables practitioners to seek reimbursement for consultations where another optometrist refers a patient. Such consultations may be performed to support colleagues in the examination, diagnosis, or management of patient complaints, ocular disease processes, or to perform assessments using specific technology or techniques.1

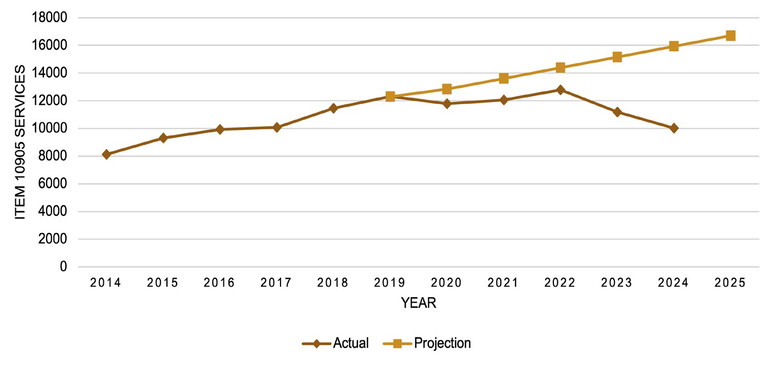

Analysis of MBS data over the past decade reveals the annual frequency of item 10905 claims, averaging 10,821 consultations or AU$699,036 in reimbursed MBS fees per annum over this period (Figure 1).2 Following its inception in November 1997, MBS item 10905 was most frequently claimed in 2022, with a total of 12,780 referred initial comprehensive consultations performed, equating to a total of $825,588 in MBS revenue.2,3

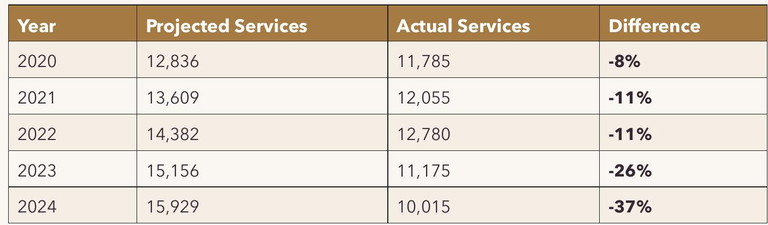

Further analysis of MBS data demonstrates a cumulative discrepancy between projected and actual 10905 claims following the 2019 COVID pandemic, with increasing disparity per subsequent calendar year as demonstrated in Table 1.2 This represents a total of 14,102 fewer referred comprehensive initial consultations over the five-year period compared to projections – totalling $911,016 in unclaimed MBS revenue – in excess of the record item 10905 service claims in 2022, by $85,428.20.

The greatest disparity occurred in 2024, with a 37% difference between projected and actual 10905 claims.2 This trend is set to continue into 2025 and beyond. Such disparity indicates that a course correction is required, and that optometrists should actively engage in clinically necessary intraprofessional referrals where appropriate.

ITEM 10905 EXPLAINED

MBS item 10905 – referred comprehensive initial consultation – may be claimed following: “Professional attendance of more than 15 minutes duration, being the first in a course of attention, where the patient has been referred by another optometrist who is not associated with the optometrist to whom the patient is referred.”3

Previously, intraprofessional referrers were to remain at ‘arm’s length’, where practitioners were not permitted to claim MBS item 10905 following intra-optometrist referral if they had the same employer.1 This was primarily to prevent incentive-driven referrals as opposed to those that were clinically indicated and genuinely focussed upon patient wellbeing. However, given that two major companies employ a substantial proportion of Australian optometrists, the peak body successfully advocated for clarification on the item descriptor and explanatory note.

This has been recently acknowledged by the MBS, with subsequent clarification provided regarding the intended interpretation of the item descriptor to better reflect the current optometric industry. This now allows optometrists within the same company to participate in intraprofessional referrals and seek MBS reimbursement when clinically indicated.3 However, item 10905 is not permitted to be claimed between optometrists within the same practice.1 It remains that no commercial arrangements or connections should exist between participating practitioners, where the item applies exclusively to patient referrals between optometrists, excluding those from medical practitioners.1,3

Table 1. Annual frequency of MBS item 10905 claims between 2014 and 2024 and projected claims from 2019.2

Figure 1. Projected and actual MBS item 10905 service claims between 2020 and 2024.2

MBS eligibility criteria stipulate that interoptometrist referrals must:1,3

• Include reference to pertinent ocular condition(s) and rationale for referral,

• Communicate all relevant information about the patient,

• Be dated and signed by the referring optometrist,

• Include the referring practitioner’s provider number,

• Be received by the optometrist providing the service, prior to provision of the service, and

• Be retained by the optometrist providing the service for a period of 24 months, along with patient clinical records.

The referring optometrist should record referral rationale within the patient’s clinical notes, in the event of a compliance audit where evidence for the claiming practice may be requested. This is particularly important because the obligation to substantiate the necessity for item 10905 lies with the referring optometrist. Further, following subsequent assessment, the patient’s account, receipt, or bulk billing form must contain the name and provider number of the referring optometrist.3 It is important for optometrists to not be coerced into facilitating retrospective referrals by other practitioners or patients, which would be contrary to the MBS item descriptor.

In the event that a patient is referred from another optometrist, and where an additional MBS item is applicable in conjunction with item 10905, both may be billed on the same day (assuming the requirements for both items are met by the optometrist receiving the referral). This principle applies to the following items when clinically indicated:1,3

• 10921–10930: Contact lens items,

• 10938 and 10940: Computerised perimetry (binocular),

• 10939 and 10941: Computerised perimetry (unilateral),

• 10942: Low vision assessment, and

• 10943: Children’s vision assessment.

As with any MBS item claim, practitioners must ensure that a clinically relevant service has been performed and documented in addition to the item descriptor being met. It is also important that a practitioner’s billing practice could be satisfactorily justified to a panel of peers in the event of a compliance activity or audit.

Further, should a patient be intraprofessionally referred to another optometrist for assessment, where subsequent ophthalmological referral is indicated, item 10905 may continue to be claimed.

CHAMPIONING INTRAPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATION

Collaboration between optometrists from different clinics provides both a prudent and innovative opportunity to optimise patient care in cases of clinical necessity, while concurrently reducing superfluous tertiary referrals.

An inter-optometrist referral model is supported by the recent Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report and Unleashing the Potential of our Health Workforce: Scope of Practice Review, which directed that health professionals should practice to their full scope in an efficient, teambased environment.4,5 This approach is also consistent with the peak body’s postulated preferred future for optometry and eye health; one that offers broad, timely access to quality and efficient eye care with a new emphasis on teamwork and collaboration.6,7

“This approach will benefit the broader health system and economy by allowing the delivery of more advanced and comprehensive patient care from within primary care”

Enhanced intraprofessional collaboration will also be beneficial as the profession fragments in the future, predicated by the Optometry 2040 report, where optometry becomes a multitiered profession with several specialisations.6,7 Specifically, a profession that possesses both a narrow, traditional scope of practice, and a more advanced ocular health practice – where specialisations may become more prominent.

This collaborative approach will benefit the broader health system and economy by allowing the delivery of more advanced and comprehensive patient care from within primary care. It will improve convenience for patients and speed the process of diagnosis, to reduce the risk of adverse sequelae and vision loss. Further, it will encourage workforce retention as optometrists embrace challenges, enjoy greater professional satisfaction, and provide rationale to receive increased remuneration.

ALLEVIATING THE PRESSURES

At a time when the pressures on Australia’s health system are mounting, due to an ageing population and growing financial constraints, to ignore opportunities for intraprofessional collaboration would be remiss.

Why put undue pressure on general practitioners’ or ophthalmologists’ waiting lists when an optometry colleague has the skills, the equipment, or the therapeutic prescribing rights to appropriately assess and manage a patient?

Why delay access to treatment for a sightthreatening ocular condition if an optometry colleague can more accurately diagnose and triage your patient in a timelier manner?

Why allow patients to incur unnecessary out of pocket expenses to receive equivalent access to eye care technology or assessment that can be provided by another optometrist?

And why force a patient living in rural or regional Australia to undergo significant travel to the city to see a specialist, if an optometrist in the same town or region can provide the required care?

NOT FOR EVERY CASE

Tasks that may be performed by nonspecialists can – and should – be intraprofessionally referred.

Tasks that require general practitioner or ophthalmological intervention – such as the need for oral therapeutics or an indication for medical or surgical care – must be appropriately triaged and referred with all relevant information to support subsequent assessment and management. Where appropriate, co-management should be offered by full-scope optometrists for consideration by the attending physician to benefit both the tertiary care provider and patient alike.

The guiding principle remains that where a practitioner determines that a patient requires a particular assessment that they are unable to provide themselves, the patient should be referred to an optometrist at another clinic who can perform the required investigation(s) in the first instance.

INTRAPROFESSIONAL REFERRAL FRAMEWORK

With any significant change comes resistance and in the case of intraprofessional referrals, it is understandable that some may be concerned about competition, reputation, or professional competence. However, such insular practice can be overcome with the adoption of an ethical framework that champions the spirit of true collaboration within the optometry profession (Table 2).

The proposed model provides practical guidance to clinicians regarding the spirit of intra-optometrist collaboration, underpinned by core principles. These fundamental ethical principles have been derived from the historical contributions of Hippocrates and Percival, in addition to more contemporary works such as those of Beauchamp and Childress.8-10 Further, the influence of health and optometry-specific charters, codes, and standards have been adapted from sources such as the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights, Australian College of Optometry

Code of Ethics, and Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency Shared Code of Conduct.11-13

This constitutes a foundation from which optometrists may operate in a professional and ethical manner to support the delivery and sustainability of intraprofessional patient care.

OBLIGATIONS FOR CLINICIANS

To ensure intraprofessional referrals are successful, it is beholden on optometrists to:

• Establish relationships with peers who possess specific skills, experience and/or access to specific eye care technology or equipment,

• Ensure timely assessment as per clinical indication. If this is not possible, or if the practitioner believes an ophthalmological referral is warranted, to communicate this to both the patient and referring optometrist,

• Provide a referral with appropriate patient and clinical information, and

• Provide a written response to the referring optometrist, detailing results of the assessment, initiated management and/or other pertinent information, such as results from specific equipment or technology, in a timely manner.

“When a practitioner cannot provide the required care, the patient should be referred to an optometrist who can...”

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Scope exists for the development of an interoptometrist referral directory and companion guide. This could exist in the form of a clinical practice guide, which outlines participating optometrists and clinics, in addition to providing further guidance regarding the spirit of intraprofessional referrals within the Australian optometry community. Such a resource would allow optometrists to promote their experience, skillsets, and access to technology or equipment, to support colleagues in other practices where clinically necessary.

CONCLUSION

Inter-optometrist referrals champion enhanced collaboration between optometrists and maximise the knowledge, skills, and capabilities available within the optometric profession. This, in turn, carries benefits for patients, clinicians, practices, and the profession alike:

Table 2. Key ethical and professional principles within an intraprofessional optometric referral framework.

• For patients, a more efficient and financially expedient eye care experience,

• For clinicians, greater career satisfaction and professional development to support the development of specific interest areas and skillsets,

• For practices, reputational growth in addition to the opportunity for increased revenue, and

• For the profession, a more collegiate and advanced optometric workforce.

Take the opportunity to proactively promote inter-optometrist referral pathways within your own locale by establishing connections with nearby optometrists and practices, enhancing collegiality and collaboration among your peers, and promoting the unique offerings of your clinic.

Thomas Ford BMedSc(VisSc) MOptom AdvCertGlauc is a full scope, therapeutically endorsed optometrist with George and Matilda Eyecare. He has experience in private ophthalmology and has completed further studies in paediatric eye care and glaucoma. Mr Ford’s interests include the therapeutic management of ophthalmic disease and myopia control, where he frequently co-manages complex cases with ophthalmology. In 2024, he was awarded the South Australian Rural Health Award for outstanding clinical excellence and patient care.

References

1. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Medicare benefits schedule book: Optometrical services schedule 2024. Available at: mbsonline.gov.au [accessed Feb 2025].

2. Services Australia. Medicare item reports: Australian Government; 2025. Available at: medicarestatistics. humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp [accessed Feb 2025].

3. Australian Government Department of Health. Medicare benefits schedule: Item 10905 2025. Available at: www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&q=10905 [accessed Feb 2025].

4. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report. 2022. Available at: health.gov.au/resources/publications/strengthening-medicare-taskforce-report?language=en [accessed Feb 2025].

5. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Unleashing the Potential of our Health Workforce: Scope of Practice Review Final Report. 2024. Available at: health.gov.au/resources/publications/unleashing-thepotential-of-our-health-workforce-scope-of-practice-reviewfinal-report?language=en [accessed Feb 2025].

6. Optometry Australia. Optometry 2040: Taking control of our future, key findings and priority commitments. 2018. Available at: optometry.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Policy/Advocacy/optometry_2040_-_key_findings__priority_ commitments.pdf [accessed Feb 2025]

7. Optometry Australia. Optometry 2040: Taking control of our future, refreshing optometry 2040. April 2024. Available at: optometry.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Policy/Advocacy/Optometry-2040-Report-2024-v3-1_ compressed.pdf [accessed Feb 2024].

8. Jones WHS. The Hippocratic Oath – Ludwig Edelstein: The Hippocratic Oath. Text, translation, and interpretation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press; 1943:vii+64.

9. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics (7th edition). 2013. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

10. Percival T. Medical Ethics; or, a code of institutes and precepts, adapted to the professional conduct of physicians and surgeons; in hospital practice, in private, or general practice. III. In relation to Apothecaries. In cases which may require a knowledge of law. To which is added an appendix; containing a discourse on hospital duties; also notes and illustrations. London: S. Russell for J. Johnson, St. Paul’s Church Yard and R. Bickerstaff; 1803. Available at: wellcomecollection.org/works/fum2udmc [accessed February 2025].

11. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights. 2020. Available at: safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/partneringconsumers/australian-charter-healthcare-rights [accessed Feb 2025].

12. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Shared Code of Conduct. 2022. Available at: ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Code-of-conduct/Shared-Code-of-conduct.aspx [accessed Feb 2025].

13. Australian College of Optometry. Code of Ethics and Conduct Standards. 2023. Available at: profession.aco.org. au/sites/default/files/2025-01/Membership-Code-of-EthicsConduct-Standards-June-2023.pdf [accessed Feb 2025].

14. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi: 10.1159/000509119.