mieducation

Collaborative Glaucoma Care: How it Works and Why it Makes a Difference

It takes considerable skill and resources to differentiate those that require treatment for glaucoma from those who do not, and to avoid over-treating.

In this article, Drs Jessica Tang and Katherine Masselos draw on case studies to demonstrate the positive health and economic outcomes that can be achieved when clinics involve credentialed optometrists working with ophthalmologists to provide shared, individualised care for patients at risk of, or living with, glaucoma.

WRITERS Dr Jessica Tang and Dr Katherine Masselos

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand how collaborative care models work,

2. Be aware of the evidence base for collaborative care of glaucoma patients,

3. Realise the requirements for collaborative care, and

4. Be aware of RANZCO’s stratification for patients at risk or with glaucoma.

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide and has been estimated to affect over 300,000

Australians.1 With an ageing population, challenges in meeting the demand within an overburdened public system can lead to delays in the detection and management of uncontrolled glaucoma. Further burdening this problem is the fact that more than half of patients with glaucoma are unaware that they have the disease.1

On the other hand, many with suspected or early glaucoma may not suffer significant visual loss in their lifetime and do not require aggressive intervention or intense monitoring. In fact, nearly 30% of referrals to public outpatient clinics for suspected glaucoma are false positives that can be managed in the community.2,3

WHAT IS COLLABORATIVE CARE AND WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE?

Collaborative clinics can involve credentialed optometrists working with ophthalmologists to provide shared, individualised care for patients through a vertical integrated care model. The concept is not new: collaborative care systems in the United Kingdom have had success since the mid- 2000s in triaging and managing low-risk glaucoma patients, providing an effective solution to the increasing burden of chronic glaucoma management.4-6 Importantly, several studies demonstrate good clinical agreement between trained optometrists and ophthalmologists.3,7,8

In Australia, there is a mounting body of evidence showing collaborative services result in fewer delays and better patient outcomes. A collaborative clinic between The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital (Melbourne) and the Australia College of Optometry targeting low risk patients showed a 12- week reduction in wait-time at six months after implementation. Further, more than three-quarters of patients were discharged to community-based optometry review, reducing the hospital waitlist by 32% at 17 months and by 92% at 28 months.9

Similar results were noted at the Community Eye Care (C-Eye-C) which involves community-based optometrist assessment and virtual review by ophthalmologists at the Westmead Ophthalmology Department (Sydney) to manage low-risk patients. Compared with standard hospital-based outpatient care, Ford et al., reported higher attendance rates (81.6% vs 68.7%) and shorter appointment wait times (median 89 days vs 386 days), with 57% of patients avoiding hospital appointments.7 Further, the costs associated with running C-Eye-C were 22% less than hospital care.

In addition, the shared care scheme between the Centre for Eye Health (CFEH) and Prince of Wales Hospital Ophthalmology Department, Sydney (POWH) reported that almost half of the ongoing care burden for patients was shifted from the public hospital glaucoma clinic to an optometry workforce.10 The re-referral rate to the glaucoma clinic was low at around 21% and there were shorter delays in follow-up with 87% of all consults seen within one month of the recommended time frame.

While each of these collaborative schemes vary in their design and are specific to their locales, their reported outcomes are similar: by diverting low-risk patients to the community, hospital resources can be reserved for higher-risk patients, reducing unreasonable waiting times for patients in need of urgent treatment.

REQUIREMENTS FOR COLLABORATIVE CARE

Following the release of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) standards required for the examination and treatment of patients with glaucoma,11 the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (R ANZCO) released guidelines for collaborative care in glaucoma in 2014. These guidelines were designed to deliver a “gold standard”, stratified framework to assist in directing lower risk patients to optometry care, while ensuring those at higher risk of disease and rapid progression receive timely care.12,13

For collaborative care to be effective, clear protocols for patient assessment, review interval, referral pathways, and confidential data sharing are essential for seamless care.12 Optometrists must be able to perform clinical examinations to the required standard and perform accurate and reliable measurements with the available equipment in the practice to engage in glaucoma screening and monitoring. Additionally, patient choice in eye healthcare provider must be considered, and they should be made aware of the treatment, management options, and skills of the professionals involved.

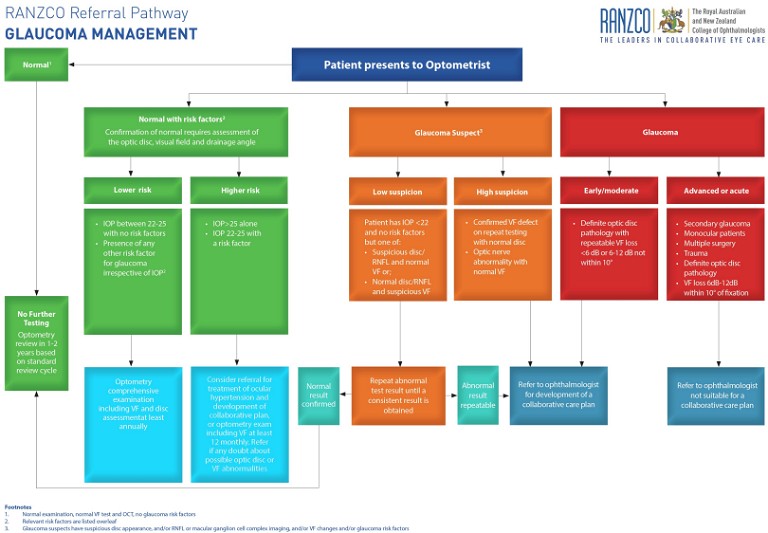

Figure 1. RANZCO referral pathway for glaucoma management.14 Download at bit.ly/3w79hz6.

The RANZCO requirements for collaborative care for glaucoma are outlined opposite.13

GLAUCOMA STRATIFICATION

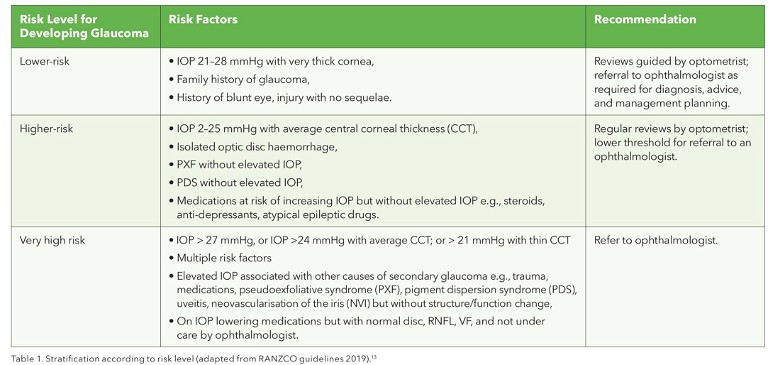

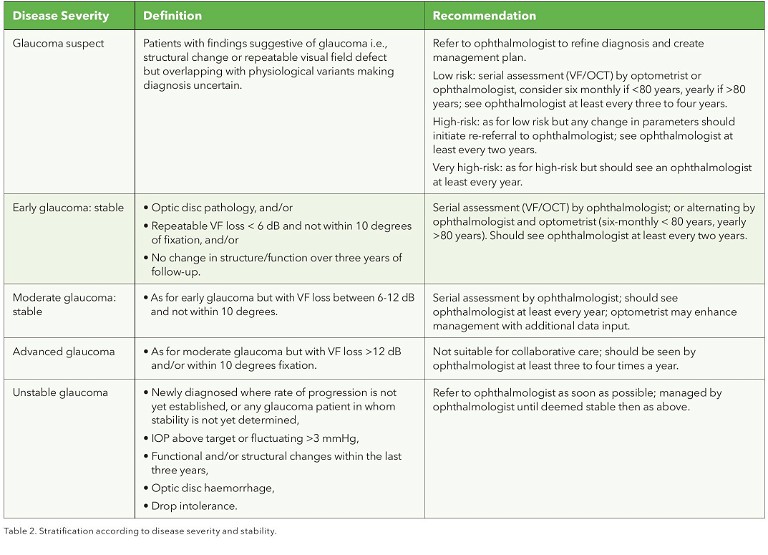

The RANZCO guidelines stratify patients into those at risk of developing glaucoma and severity of disease, providing management recommendations and recommended monitoring intervals (Tables 1 and 2).

HIGHLIGHTING THE EVIDENCE

The CFEH was established as a referralonly service to support the diagnosis and management of common eye disorders in the community.3 Run by therapeutically endorsed, experienced optometrists, CFEH collaborates closely with ophthalmologists from the Prince of Wales Hospital to manage early or stable glaucoma through the Glaucoma Management Clinic (GMC). The criteria for collaborative care at the centre include early-to-moderate glaucoma, long-term stable disease, and no other significant ocular comorbidities.

There are three pathways in which a patient can enter the GMC:2

1. Direct community referral, typically from an optometrist, for high-risk glaucoma suspects requiring confirmation of diagnosis and treatment initiation,

2. Internal referral from the CFEH general clinic for further comprehensive glaucoma assessment, and

3. Direct referral from Prince of Wales Hospital.

Using real case examples below from the CFEH, GMC, and Prince of Wales Hospital, we highlight scenarios where shared care can safely and effectively reduce delays in reviews, improve access for higher risk patients, and reduce unnecessary referrals to hospital eye clinics, thereby reducing public waitlists and potentially health system costs.

Case One

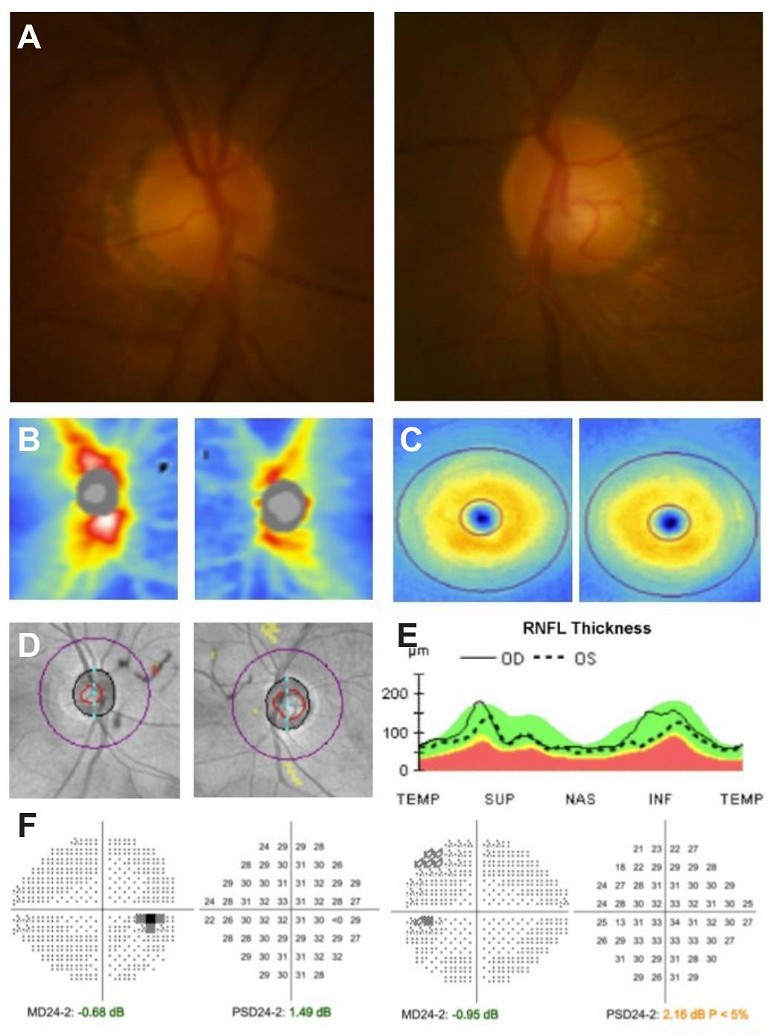

A 62-year-old male was referred to CFEH general clinic in January 2022 by a community optometrist (Figure 2, below). He had been taking Latanoprost since 2018 but had been lost to follow-up with his ophthalmologist. He had a strong family history of glaucoma but there was no significant past ocular history. His past medical history included type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolaemia. His best corrected vision was 6/6 in both eyes. Pre-treatment intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 29 mmHg in both eyes with central corneal thickness right 525 µm, left 530 µm. Gonioscopy found open angles in both eyes. Dilated fundus examination showed a cupto-disc ratio of 0.4 in the right and 0.5 in the left. Humphrey visual field (HVF) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness was normal. Six-monthly reviews over 18 months with optometrists at CFEH showed stable structural and functional assessments, and the patient has avoided the need for a public hospital appointment. He will continue to be reviewed at the GMC on a two-yearly basis with six monthly reviews by optometrists at the centre.

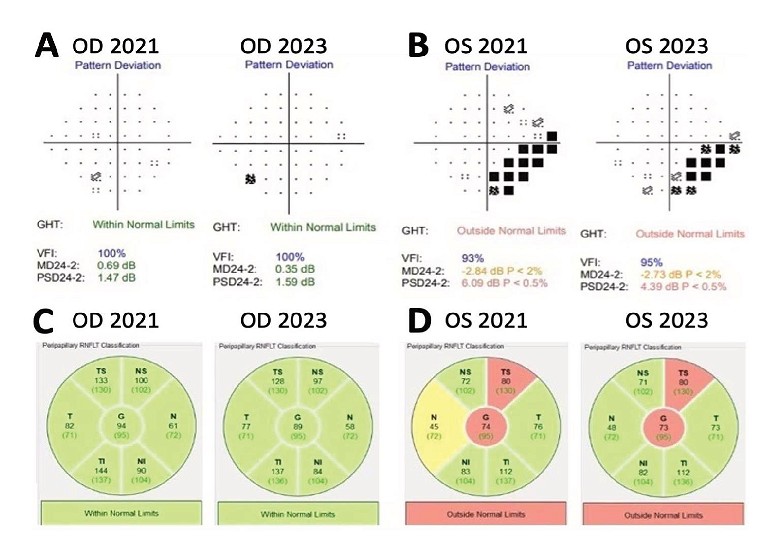

Figure 3. Case two: A. 24-2 HVF of the right eye in 2021 and 2023, showing no defect; B. 24-2 HVF of the left eye, showing stable inferior nasal step over the two years; C. Spectralis OCT RNFL within normal limits in the right eye;D. Spectralis OCT RNFL showing superotemporal thinning in the left eye that has remained stable over two years.

Figure 2. Case one: A. Disc photos of right and left eye; B. Cirrus OCT RNFL thickness map showing normal thickness; C. OCT ganglion cell complex thickness map showing normal thickness; D. OCT RNFL deviation map; E. OCT temporal-superior-nasal-inferior-temporal graph; F. 24-2 HVF showing no visual field defect.

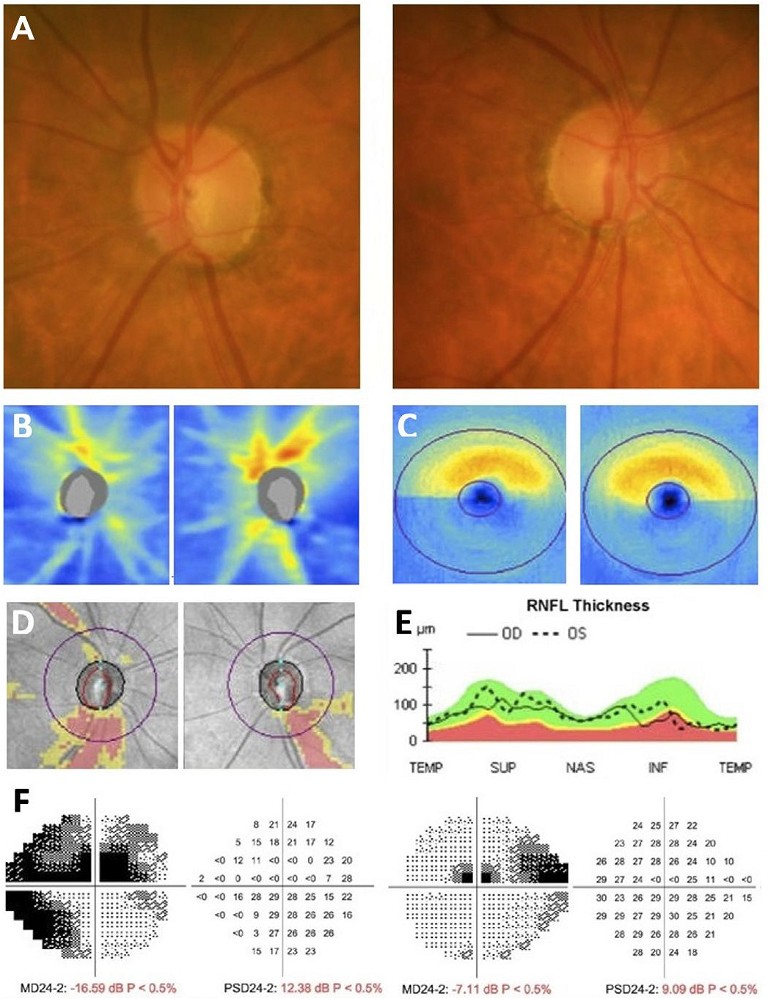

Figure 4. Case three: A. Disc photos of right and left eye showing inferior notch in both eyes; B. Cirrus OCT RNFL thickness map showing inferior thinning in both eyes; C. OCT ganglion cell complex thickness map showing inferior thinning in both eyes; D. OCT RNFL deviation map; E. OCT temporal-superior-nasal-inferior-temporal graph; F. 24-2 HVF showing right eye superior arcuate defect involving fixation with inferior nasal step and left eye superior nasal step and central fixation defect.

Collaborative Care for Glaucoma Should:

• Be patient focussed,

• Implement evidence-based healthcare,

• Provide the patient access to the most appropriate healthcare provider in a timely fashion,

• Clearly define the roles for healthcare providers and facilitate effective communication,

• Ensure tests and measures are appropriate and necessar y,

• Reduce unnecessary healthcare provider visits,

• Avoid under - or over-treatment of patients, and

• Ensure patients have access to the full range of treatment alternatives of which they should be made fully aware.

Patients Not Suitable for Collaborative Care:

• Complex ocular pathology/secondar y glaucoma except PXF/PDS,

• History of eye trauma with established glaucoma,

• Monocular patients with glaucoma,

• Patients who have undergone multiple ocular surgeries, and

• Patients with advanced glaucoma (stable or unstable).

Case Two

A 68-year-old female was initially referred by a community optometrist to Prince of Wales Eye Clinic for cataract assessment ( Figures 3). On initial review, her vision was 6/6 on the right eye and 6/12 on the left. IOP was 19 mmHg on the right and 20 mmHg on the left. She had bilateral cataracts (worse on the left), and was noted to have asymmetric cupping with a cup to disc ratio of 0.5 on the right and 0.7 on the left. The left neuroretinal rim was thin superiorly, which corresponded to a left inferior nasal step defect on 24-2 HVF. She was diagnosed with early normal tension glaucoma. After routine left cataract surgery, she proceeded to have left selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) with IOP improving to 11 mmHg. Follow-up at two years showed no change to HVF or RNFL and she was discharged to CFEH for monitoring, with secure transfer of her OCT and HVF for ongoing progression analysis.

Case Three

An 80-year-old female was seen at GMC with advanced glaucoma ( Figure 4). She did not have any significant past ocular history or family history of ocular conditions. She had hypertension and was on an angiotensin-II receptor blocker, which she took in the morning. Her best corrected vision was 6/9 in the right and 6/24 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 17 mmHg in both eyes, with central corneal thickness right 578 µm, left 583 µm. Gonioscopy found open angles in both eyes. Dilated fundus exam showed cup-to-disc ratio of 0.6 with deep inferior notching in both eyes. HVF on the right showed superior and inferior loss involving fixation superiorly with mean deviation of -16.59 dB. Similarly, the left showed superior loss involving fixation with MD -7.1 dB. There was corresponding inferotemporal RNFL thinning in both eyes. Given the significant field loss involving fixation, she was deemed inappropriate for GMC management and was referred to the POWH glaucoma clinic. She was seen within a month of the referral and was commenced on Latanoprost in both eyes for normal tension glaucoma. The patient was scheduled for review again at four weeks to assess compliance and treatment response and will continue to be monitored in the public hospital.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR COLLABORATIVE CARE

Collaborative care must be tailored to the needs of the local community as well as the resources available to healthcare providers. There must be continual refinement, feedback between providers, and professional education and upskilling to deliver quality patient care. Further longitudinal studies assessing safety, sustainability and cost-effectiveness will be essential to assist in the expansion of these models in Australia, especially regionally and rurally where healthcare is often disadvantaged. Nevertheless, a growing body of evidence shows collaboration between optometrists and ophthalmologists, within a formalised framework using national guidelines, provides an effective solution to managing the increasing burden of chronic glaucoma management.

To earn your CPD hours from this article, visit: mieducation.com/collaborative-glaucoma-carehow-it-works-and-why-it-makes-a-difference.

References available at mivision.com.au

Dr Jessica Tang BMedSc MBBS (Hons) PhD completed her PhD in Glaucoma at the Centre for Eye Research Australia and University of Melbourne. She is currently a RANZCO accredited ophthalmology registrar at the Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney.

Dr Katherine Masselos MBBS (Hons) B.Optom (Hons) MPH FRANZCO specialises in cataract and glaucoma surgery, practising in Sydney. She completed sub-specialty glaucoma training at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, in the United Kingdom. Dr Masselos is a staff specialist at Prince of Wales and Sydney Eye Hospitals where she enjoys teaching clinical and surgical skills to future ophthalmologists. She is actively involved in research and has published in international journals.