mieducation

Glaucoma and Ocular Surface Disease

Ocular surface disease (OSD) is a debilitating condition that causes chronic ocular discomfort and impaired vision. It occurs at a higher rate in patients receiving treatment for glaucoma and undermines one of the primary treatment objectives in glaucoma management – to maximise quality of life (QoL). Carly James and Dr Colin Clement discuss the major risk factors for developing ocular surface disease in patients with glaucoma and explain why minimally invasive glaucoma surgery may be an optimal approach to treatment.

WRITERS Carly James and Dr Colin Clement

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand the role of the ocular surface,

2. Be aware of how the integrity of the ocular surface can be disrupted, and

3. Understand how minimally invasive glaucoma surgery can protect the ocular surface by minimising the use of topical glaucoma drops.

A major risk factor for developing OSD is the use of topical glaucoma eye drops, in particular those containing preser vatives such as benzalkonium chloride (BAK ).

Treatment strategies that minimise the need for glaucoma eye drops, or eliminate the need altogether, are likely to be of great benefit in limiting the impact of OSD. One such strategy is minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), a rapidly evolving treatment option for mild to moderate glaucoma. MIGS has been shown to safely and effectively lower intraocular pressure (IOP), and reduce the ocular medication burden, which has the dual benefit of helping stop glaucoma progression and lessening the likelihood of ongoing symptomatic OSD.

THE OCULAR SURFACE AND OSD

The lacrimal gland, eyelids, tear film, conjunctiva, lacrimal canals, lacrimal puncta, trigeminal, and facial nerves are a system collectively known as the ocular surface.1 The ocular surface is unique in that it has direct exposure to the elements. If this barrier system breaks, the sensitive cornea becomes exposed, and irritation ensues.2 OSD is an umbrella term encompassing diseases, disorders, mechanical, and physiological issues that disrupt the natural barrier protecting the eye.3

Dry eye syndrome (DES), blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction, and toxicity from chronic use of topical eye drops are common causes of OSD.4 While some patients may be asymptomatic, an overwhelming number of patients experience varying levels of blurred vision, discomfort, irritation, and epiphora, among others.1,4 As the severity of these symptoms increases, so does the impact on a patient’s quality of life. A common complaint of DES is blurred vision, which is known to impact work productivity, driving, reading, computer use, and even watching television.5,6

The percentage of the general population with dry eyes is reported at 15%, though levels vary with age and other factors.4 A small study of patients attending a general ophthalmology clinic in an Italian hospital, performed in 2014, found that dry eye disease (DED) was the most common type of OSD, making up 58% of the OSD cases. Other causes of OSD included infections, allergies, eyelid pathologies, and trauma. It was reported that 37% of patients were asymptomatic.1

GLAUCOMA AND OSD

As glaucoma is a lifelong , potentially progressive disease, drop usage or alternative pressure lowering treatments are required to prevent disease progression from the point of diagnosis.7 Hypotensive eye drops are the most common treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).4,7 While allergic reactions are a possible cause of side effects from topical treatment, the more common cause of discomfort from drops are the preser vatives.8 Many pressure lowering eye drops contain preservatives, which with repeated use can induce ocular surface changes and subsequently OSD. Correct instillation of eye drops takes practise, they are easily contaminated by hands, or eye lashes if one gets too close to the eye. Preservatives are antimicrobial in nature; thus, they are added to eye drops to reduce the growth of bacteria in the compound.9

The most used preservative, BAK, is known as a quaternary ammonium compound that disrupts cell membranes and prevents bacterial growth. In doing so it also increases the evaporation of the lipid layer of the tear film, thus causing dry eye symptoms.4 Studies have shown that topical drops containing lower levels of BAK have less impact on tear film break-up time as opposed to those containing higher levels. Furthermore, studies comparing preserved and non-preser ved drop options indicate that the tear film evaporates quicker in preserved options. Thus proving that the preservative is the more likely cause of ocular surface discomfort rather than the active ingredients.8,10

It is reported that 59% of glaucoma patients have symptomatic OSD.11 Chan et al. reviewed patients in an Australian hospital and found that 39% of glaucoma patients also have significant OSD vs 18% of the control group.12 It is important to acknowledge that clinical trials in glaucoma patients do not truly represent the greater glaucoma community as many studies exclude those with pre-existing OSD. They also generally have a wash out period for eye drop use and thus the reported ocular surface discomfort could be lower than if patients were on continued topical treatment.4

As glaucoma is a progressive disease, many patients eventually require multiple eye drops.8 Studies have shown that OSD symptoms increase as the amount of topical hypotensive drops increases.4,11 OSD symptoms have also been found to progress with time post glaucoma diagnosis,13 and with increasing severity of glaucoma.14

Discomfort experienced from topical treatment is a commonly identified reason for reduced compliance or even discontinuation of said treatments.8 With increasing symptoms of OSD, there is an increase in incidence of depression and anxiety.11 A common result of this change in mental status is a change in the general wellbeing of the patient, including adherence to medical regimes.15 Specifically in glaucoma patients, self-reported noncompliance to topical therapy was linked to depression.16 Patients that experience more severe side effects from their topical treatment have been shown to attend clinics on an increased basis and report a higher impact on their quality of life.12,17 Poor adherence to treatment is a risk factor for severe vision loss and glaucoma related blindness.8

Glaucoma treatment aims to lower the IOP of patients, which in turn slows or prevents damage to the optic nerve head.4,18 Traditionally, the first line of treatment for POAG is topical hypotensive therapy and when topical treatments are having an adverse effect or are no longer providing effective IOP lowering , laser or surgical options are considered.19 While these inter ventions either enhance existing pathways or create new pathways for aqueous drainage, their approach, expected IOP reduction, and risk profile are what differs. Traditional surgeries involving conjunctival dissection may also be associated with an increase of ocular surface discomfort.11 These limitations and potential complications of invasive glaucoma surgery have been catalysts for the development and growth of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS).

MINIMALLY INVASIVE GLAUCOMA SURGERY

MIGS is a relatively new and exciting group of surgeries that aim to safely and effectively reduce IOP and dependency on topical therapy using a minimally invasive approach.20 Current MIGS procedures have been proven to reduce IOP to mid to low teens. Because of this modest reduction in pressure, they are currently recommended for those with mildto-moderate glaucoma and are not commonly suggested for those needing even lower pressures, such as those with severe glaucoma and at a high risk of progression.19,21

The first MIGS procedures were performed in Australia in 2014, with the first device used being the iStent (first generation). Since then, multiple MIGS devices have been approved and their use has rapidly grown. The Australian Government approved MIGS as a standalone procedure in 2020, providing greater accessibility for use in eyes without cataract or those that have previously had cataract surgery.

Gillman and Mansouri refer to four approaches to MIGS,22 separated by the location of the procedure:

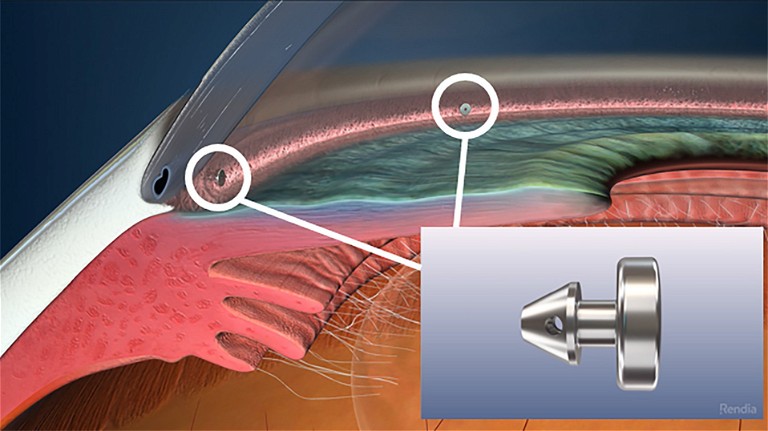

1. Schlemm’s canal: Dilation of Schlemm’s canal, bypassing the trabecular meshwork (via stent or removing part of the meshwork) or trabeculotomy. Examples: iStent (first generation) and iStent inject, ab interno canaloplasty, Hydrus.

2. Suprachoroidal space: exploiting the uveoscleral pathway by the insertion of shunts to aid drainage from the anterior chamber, through supraciliary space and into the suprachoroidal space. Examples: Miniject, CyPass (retracted), iStent Supra (undergoing clinical trials).

3. Subconjunctival space: devices inserted creating a new pathway for fluid between the anterior chamber and subconjunctival space. This type of MIGS creates a bleb. Examples: Xen and Preserflo.

4. Ciliary body: Applying laser to the ciliary body to reduce the production of aqueous humour.

A meta-analysis of MIGS trials performed by Gillman and Mansouri showed an IOP reduction of between 15.3–50%, depending on the procedure, although it is not clear whether these procedures were standalone or in conjunction with cataract surgery.22 From this analysis, the two most commonly performed MIGS procedures in Australia, iStent inject and Hydrus, were associated with similar mean IOP reductions of around 30%.22 In a systematic review on standalone iStent surgery, Healey et al. reviewed 13 studies and found that the standalone stent reduced both IOP and medication burden across the range of follow-up times, currently reported up to 60 months post-surgery.23 Pyfer et al. reviewed diurnal IOP fluctuations post canaloplasty using the OMNI Surgical System combined with cataract surgery and trabeculotomy. Results indicated a reduction in not only the mean IOP at different times of the day, but also a decreased peak IOP when compared with pre-operative peaks.

iStent Inject (Glaukos).

A limitation of this study is that it was performed over seven daytime hours.24

As glaucoma is potentially progressive in nature, at some point after a patient’s diagnosis we would expect that their cataracts would reach a point requiring extraction. This creates an ideal situation to perform a combined procedure of cataract extraction with the inclusion of MIGS. This combination surgery allows a possible reduction in the topical medication burden and thus could reduce the severity of OSD.21,22 A literature review performed by Agrawal and Bradshaw in 2016 indicated that both iStent and Hydrus implants when combined with cataract surgery were able to provide a further IOP lowering effect than cataract surgery alone.19 They also reported that both cataract surgery alone, and when in combination with MIGS procedures, provided a reduction in the amount of topical glaucoma medication required post-operatively.19

THE IMPACT OF MIGS ON OSD

There are only a few studies so far that report on OSD and QoL in patients preand post-MIGS procedures. Schweitzer et al. used objective and subjective measures of OSD and compared before surgery and three-months after surgery in eyes undergoing cataract surgery with iStent.25 At three months, there had been a 60% reduction in medication in the cohort with 55% medication free compared to none before surgery. This was associated with significant improvements in OSD measures including a 71% reduction in corneal staining , a 56% reduction in the OSD index score, a 48% improvement in the tear break-up time, and a 14% reduction in conjunctival hyperaemia.25 Jones et al. performed a similar study, also examining the impact of cataract combined with iStent, but additionally reported measures of QoL including the glaucoma severity scale (GSS) and glaucoma quality of life (GQL-15).26 They also found improvements in OSD following surgery and importantly reported that QoL measures also improved, suggesting MIGS may be a better approach to IOP lowering in these patients. Of note was the finding that patients reporting the greatest improvement in QoL were those that were drop free post operatively.26 One confounder in both studies however, is the fact that eyes had combined surgery. Simply undergoing cataract surgery may convey benefits in terms of reduced medication burden, improved OSD signs and symptoms, as well as improved QoL. So far there are no studies reporting OSD outcomes and/or QoL in eyes that have had MIGS as a standalone treatment. However, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) iStent inject pivotal trial compared combined surgery with cataract surgery alone and found that the use of iStent inject conveyed additional benefit in terms of OSD and QoL scores.27 Outcomes following standalone MIGS will be an area of interest for future research as well as examining the individual benefit of different types of MIGS.

“ Dry eye syndrome (DES), blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunc tion and toxicity from chronic use of topical eye drops are common causes of OSD ”

CASE STUDY

Mrs Dean,* an 81-year-old female with normal tension glaucoma, presented for a second opinion regarding her cataract and blepharitis. She had experienced declining vision and long-term eye discomfort that had been managed with lubricants and antiinflammatories. A right lower lid chalazion had required an incision and curettage eight months earlier. For the preceding 12 months, she had planned to undergo cataract surgery, but this had been repeatedly delayed as lid margin inflammation could not be controlled. At presentation, treatment consisted of Simbrinza BD OU, FML daily OU, Hyloforte 5-6x daily OU, Cellufresh PRN OU and oral doxycycline 100 mg daily as well as oral Crestor for hypercholesterolaemia and oral Somac for reflux .

At the initial examination, her best corrected visual acuity measured R 6/12+2 and L 6/12 with IOP R 12 mmHg and L 13 mmHg. Mild lid margin inflammation was seen bilaterally, and a few corneal punctate erosions were noted on each side with a tear break-up time of approximately 10 seconds. Moderate nucleosclerotic cataract was present on each side, open iridocorneal angles were seen, bilateral posterior vitreous detachments were present, the maculas appeared healthy, and the peripheral retinas were normal. Optic nerves had an estimated cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3 on each side. There was a focal retinal nerve fibre layer defect on the right, yet visual fields remained full.

History and findings suggested the presence of pre-perimetric open-angle glaucoma with reduced vision due to the combined effect of cataract and OSD, and that the OSD was likely caused or exacerbated by Simbrinza. As a result, the patient required a treatment plan that would remove the cataract and the need for IOP-lowering topical treatment, which in turn would aid in the management of the OSD. A decision was made to undergo cataract surgery with iStent inject. Surgery proceeded routinely and recovery was uneventful, achieving uncorrected distance acuity of 6/6 bilaterally with IOP in the range 8–10 mmHg without Simbrinza. Ocular surface symptoms improved (less reported discomfort and stable vision) and Mrs Dean was able to stop Doxycycline, FML and Cellufresh, and reduce Hyloforte to PRN (1–2x daily on average). This has been maintained for four years and there has been no visual field or optic disc imaging evidence of glaucoma progression during this period.

In this case, the use of cataract surgery combined with an ab interno trabecular bypass stent (iStent inject) has improved the patient’s quality of life by improving visual acuity, reducing the burden of medication, and reducing the ocular surface symptoms. The preceding strategy that consisted of targeting the OSD and then proceeding to cataract surgery once controlled was not ever likely to work because the topical treatment, in this case Simbrinza, was a significant factor in the presence of ongoing OSD.

CONCLUSION

Glaucoma patients using hypotensive eye drops are exposed to active ingredients to elicit a reduction in intraocular pressure as well as other chemicals including preservatives. These chemicals have the potential to damage the ocular surface and cause OSD, which in turn may diminish QoL. MIGS provides a relatively safe and effective treatment option that can provide a modest reduction of IOP and allow patients to reduce or eliminate dependence on eye drops. Furthermore, most MIGS do not require conjunctival dissection, therefore preserving conjunctival integrity in the event that traditional filtration surgery may be needed in the future. Clinical experience suggests MIGS conveys benefit in terms of improved OSD signs and symptoms. This is supported by the limited research to date suggesting both OSD and QoL are positively influenced by the use of MIGS. There remain large gaps in our knowledge including the benefit of standalone MIGS and the benefit of different types of MIGS – these will no doubt be areas of focus for future research.

To earn your CPD hours from this article, visit mieducation.com/glaucoma-and-ocularsurface-disease.

* Patient name changed for anonymity.

References available at mivision.com.au

Carly James BMedSci MOrth is the Lead Orthoptist at Eye Associates in Sydney.

Dr Colin Clement MBBS BSc (Hon) PhD FRANZCO FGS is an ophthalmologist with expertise managing cataract and glaucoma. He is an honourary medical officer at Sydney Eye Hospital, a clinical senior lecturer at Sydney University and is director of glaucoma surgical wet lab training at the Sight Foundation Theatres (Sydney). Dr Clement is one of only two ophthalmologists in Australia to be awarded fellowship to the International Society of Glaucoma Surgery. Dr Clement is a founding editor for the journal Clinical and Experimental Vision and Eye Research as well as associate editor for the Journal of Current Glaucoma Practice. He is the author of more than 50 research articles, six book chapters and is the coeditor of a textbook on glaucoma.