mieducation

New Evidence on Eating Patterns: Changes to AMD Nutrition Guidelines

To celebrate Macula Month, Macular Disease Foundation Australia (MDFA) has launched updated nutrition guidelines for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The new guidelines suggest eating patterns, such as Mediterranean or Asian diets – rather than specific foods – may be a key to AMD prevention and progression. And there’s new evidence that drinking alcohol is a risk factor for developing AMD.

WRITERS Dr Kathy Chapman, Laura Baker, Ka Hang Cheong, Victoria Heaton, Margaret Nicholson, and Professor Victoria Flood

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand the latest evidence linking diet and prevention/progression of AMD,

2. Realise how a systematic review of epidemiological studies can be used to distinguish between convincing and probable evidence and how this translates to nutrition guidelines,

3. Provide evidence-based nutrition advice for people at risk of AMD, and

4. Understand the mechanisms of action for how diet and nutrients may protect against the onset of AMD.

As AMD is the leading cause of vision loss in Australia and affects 1.5 million Australians,1 MDFA was keen to understand the latest published research about diet and whether it can help reduce the long-term risk of developing AMD or progressing to late AMD. Any steps to reduce risk and help maintain vision are vital to improving quality of life and overall health status of Australians.

Eye healthcare professionals, including optometrists and ophthalmologists, often deliver diet advice to their patients.2,3 A survey of Australian optometrists indicated that two-thirds of practitioners regularly discuss the impact of diet on eye diseases, while 91% routinely recommend nutritional supplements to patients with AMD.2 This advice may vary among practitioners as there are currently no official dietary guidelines for eye health or AMD, with most practitioners relying on peer-reviewed journals (86%), colleagues (48%), or meta-analyses of clinical trials (48%) for sources of information.2 There is also strong interest from the community in MDFA’s nutrition information, with Macula Menus one of our most popular resources.

MDFA is cognisant that specific dietary advice must be based on the best and latest published scientific evidence. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review evaluating the evidence for the role of dietary patterns, foods, nutrients, and supplements in preventing AMD and/or slowing its progression.

WHAT WE CURRENTLY KNOW

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including the Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS1 and AREDS2), have reported the efficacy of multi-antioxidant supplements in reducing the risk of late AMD.4 An association between antioxidant-rich foods and AMD has also been noted in epidemiological research since the 1990s, mainly in cohort or observational studies.5 This includes the Mediterranean diet, categorised by high consumption of plant-based foods and monounsaturated fats derived mainly from extra virgin olive oil.6 The high intake of vegetables, fish, and plant-based proteins in an Asian-style diet pattern, traditional in Japan and other south-east Asian countries, has also been associated with lower incidence of AMD.7

Other epidemiological studies have suggested that food components such as antioxidants (lutein, zeaxanthin, found in green leafy vegetables, corn and eggs; and beta-carotene in orange and red coloured fruits and vegetables), long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (found predominantly in fish), vitamins (A, B6, C), and minerals (calcium, magnesium, zinc) may be associated with delaying the development of late AMD to some extent.5,8,9

THE MDFA REVIEW

Systematic reviews are considered the highest level of evidence to inform clinical and public health decisions.10 While there have been many published systematic reviews describing the association between nutrition and AMD, a 2018 study found the rigour of these reviews varies significantly in methodological quality, lack of adherence to established design protocols, and inadequate reporting of conflicts of interest.11 Given this, MDFA identified the need for a robust and rigorous systematic review of published systematic reviews that presents a reliable and comprehensive picture of the impact of foods, eating patterns, nutrients, and dietary supplements on AMD.

The review was undertaken in partnership with an AMD nutrition expert and two student dietitians from the University of Sydney. This systematic review was conducted using best practice recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol.12 Systematic reviews were included if they investigated the association between any diet, food, macro- or micronutrients, and/or dietary supplements and AMD (early, intermediate, late atrophic, and/or neovascular) in adults.

MDFA included systematic reviews of observational studies as well as reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). While RCTs are the gold-standard design for comparative studies, observational studies like cohort studies (such as the Blue Mountains Eye Study9 ) are often the only practical, feasible, and ethical means of conducting studies looking at associations with foods.

We searched electronic databases including EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Database. Initially 575 studies were identified, with 21 systematic reviews included in the final analysis. This included 157 primary research studies from around the world. MDFA’s review assessed the level of bias in the included studies using the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool,13 and the quality and certainty of evidence using the grading of recommendation, assessment, development, and evaluation (GR ADE) approach.14 The level of certainty of evidence indicates how confident we are that that there is strong association between the dietary factor and AMD.

KEY FINDINGS

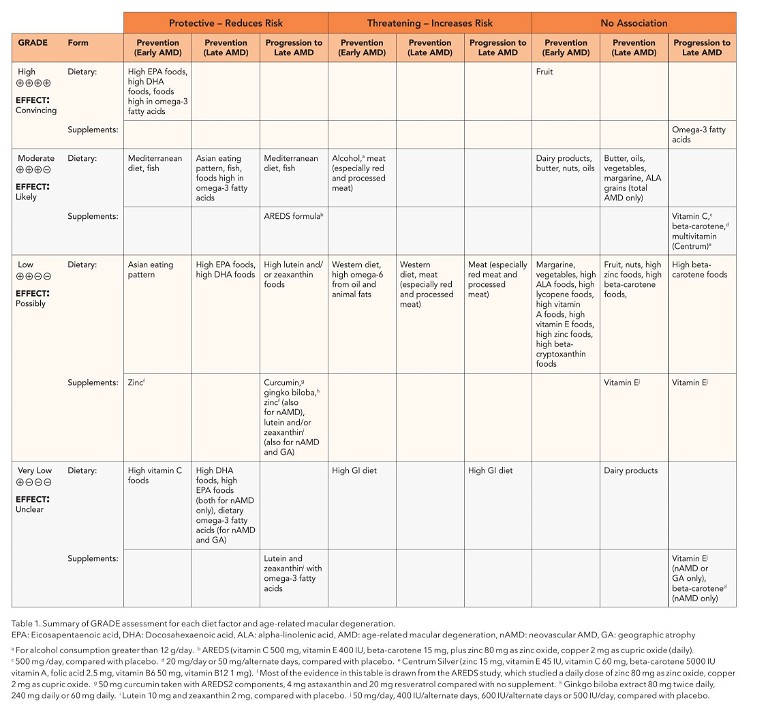

MDFA’s systematic review found that nutrition offers a promising pathway of reducing the risk of development and progression of AMD (see Table 1). A key finding was that dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish consumption were frequently reported to protect against AMD. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids include eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and are found in highest concentrations in fatty fish (i.e., salmon, tuna, mackerel), so it is likely that this finding goes hand-in-hand. High consumption of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids convincingly decreased the risk of early AMD and was also likely associated with a decreased risk of late AMD and slowing progression from early to late AMD (moderate certainty of evidence).

High consumption of fish was found likely to be protective against developing AMD, as well as delaying progression of AMD (moderate certainty of evidence). Interestingly, MDFA found that omega-3 fatty acid supplements were convincingly not associated with slowing the progression of AMD (high certainty of evidence) – as will be discussed further on.

A new finding for MDFA was that high adherence to the Mediterranean diet was likely to be associated with lower risk of early AMD and delaying progression to late AMD (moderate certainty of evidence). Similarly, an Asian eating pattern likely reduces the risk of developing late AMD (moderate certainty of evidence) and may reduce the risk of developing early AMD, although this was rated as low certainty of evidence.

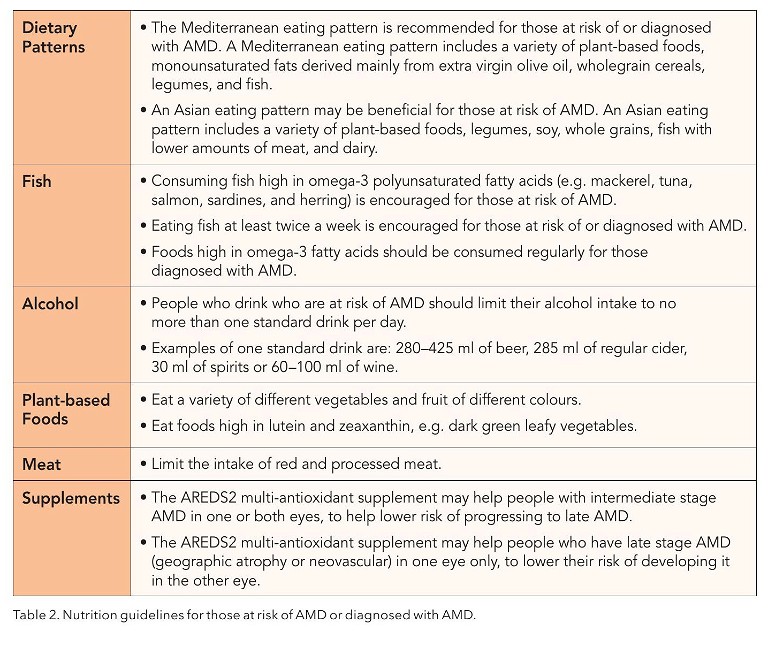

This focus on an eating pattern is a novel finding as most previous advice has centred around specific foods and single nutrients. This advice to consider the overall eating pattern has been updated in MDFA’s nutrition recommendations (see Table 2).

Additionally, eating foods rich in lutein and zeaxanthin, which are found in green leafy vegetables (e.g., kale, spinach, broccoli, peas, and lettuce) corn, and egg yolks, were likely associated with reduced risk of developing late AMD or progressing to late AMD (moderate certainty of evidence).

Multi-antioxidant supplements (including the AREDS formulation) were associated with delaying progression of AMD, but not preventing early AMD (moderate certainty of evidence). The latest AREDS formulation, which has been tested in an RCT study design, includes lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamin C, vitamin E, copper, and zinc.15 Lutein and zeaxanthin were included in place of beta-carotene, which was part of the first AREDS formulation.15

Some new evidence uncovered by MDFA was that drinking alcohol (more than ~one standard drink /day) was likely associated with higher risk of developing early AMD (moderate certainty of evidence). This is important information to share and will now become part of our nutrition messaging for community members.

High meat consumption (especially red and processed meat) was also associated with a greater risk for developing early AMD (moderate certainty of evidence).

SYNERGISTIC EFFECT OF FOOD

A key finding from this study is the importance of considering overall eating patterns rather than focussing on single nutrients and foods. While people often like to improve their diets by consuming individual nutrient supplements or so-called super foods; in reality, nutrition concerns the long-term, overall diet. The concept of ‘food synergy’, the concerted action of food constituents on overall health, is an important message to highlight.16 Studying foods consumed regularly together may demonstrate an enhanced effect on health, compared with studying foods or nutrients in isolation.16 This may explain why the Mediterranean and Asian eating patterns were consistently linked to a lower risk of developing AMD and slowing progression of AMD, while the evidence was less certain for a high dietary intake of individual foods and nutrients. Mediterranean and Asian dietary patterns are similar in terms of having a high intake of fresh fruit and vegetables and moderate intake of fish, nuts, and seeds, and low to moderate intake of meat and dairy products.6,7 However, an Asian eating pattern has a high intake of rice, rice products, and soy products,7 whereas the Mediterranean diet is based on regular use of olive oil and cereal products (e.g., wholegrain bread).6 Common to both eating patterns is a high intake of fish, foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidants,6,7 which not surprisingly, are the foods that were found to have the strongest protective associations (high certainty of evidence and moderate certainty of evidence).

SPECIFIC FINDINGS

Dietary Patterns

MDFA was eager to understand why the Mediterranean and Asian diets could play a role in AMD risk reduction and progression. The answer may lie in the anti-inflammatory properties of these diets. Research has shown that inflammation plays a role in the development of AMD as ocular tissues are vulnerable to oxidative stress.17,18 Adhering to a Mediterranean diet has been linked to lower levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in the blood.19 This may be due to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties found in fruit, vegetables, and fish. Whereas research consistently suggests a Western diet is linked with higher inflammation in the body, which may explain why a Western diet was possibly associated with increased risk of developing AMD.20

As the primary studies investigating the relationship between dietary patterns and AMD were all observational (mainly cohort studies),21 it is unclear whether following the dietary pattern led to a reduction in risk or whether those following the Mediterranean and Asian eating patterns were more likely to engage in other health promoting behaviours that might contribute to a lower risk of AMD.

Fish

MDFA found the evidence was most consistent for fish consumption in reducing the risk of AMD. Fish is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids including EPA and DHA, which are essential structural elements in photoreceptors.18 These fatty acids are important in cell membrane maintenance and retinal repair following oxidative stress. They may additionally inhibit development of plaque and assist retinal vessel health, including reduction of inflammation and depress vascular endothelial growth factor ( VEGF). Studies conducted in Japan with regular high consumption of fish high in omega-3 fatty acids tend to find a stronger protective effect.22 Therefore, regularly eating fatty fish (e.g., salmon, tuna) may be helpful in reducing AMD risk. This is a key recommendation in MDFA’s nutrition guidelines.

Plant-Based Foods

Eating patterns with high intakes of vegetables, fruit, legumes, nuts, grains, and plant-based oil (mainly extra virgin olive oil) indicated a possible protective effect against the risk of AMD.11 Given vegetables are high in lutein and zeaxanthin, especially dark green leafy vegetables like spinach,24 the limited association found in MDFA’s review does not necessarily indicate that these foods are not important in managing risk of AMD. As discussed previously, single nutrients or foods in isolation may not capture the synergistic effects of different foods and nutrients consumed together in the context of an overall diet.16

Meat

High meat consumption was associated with an elevated risk for early AMD, particularly red and processed meat. One potential explanation for this association is the presence of haem iron in red meat. Haem iron stimulates the body’s production of mutagenic nitroso-compounds, which are metabolised into highly reactive methylating agents and can be detrimental to the retina.25 However, iron plays a major role in the body, so consuming red meat in moderation can be balanced with managing the risk for AMD and overall health.

Nutrients From Food

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA and EPA, were consistently associated with the prevention and progression of AMD.22,27- 30 Omega-3 fatty acids, found in seafood, nuts, and egg, have been shown to influence inflammatory reactions and oxidative stress in various diseases.31

The DHA omega-3 fatty acid is a crucial component of the membranes surrounding photoreceptor outer segments in the retina and has properties that can combat inflammation and angiogenesis, both of which can contribute to the pathogenesis of AMD.31 The concentration of DHA in the retina is influenced by diet.31 However, EPA is not concentrated in the retina but serves as a precursor to DHA, so its metabolites may have similar effects on the pathogenic processes of AMD.31

High intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin, commonly found in dark green leafy vegetables, eggs, and corn, were likely associated with helping prevent AMD or progressing to late AMD (moderate certainty of evidence).24,32 Lutein and zeaxanthin are present in high concentrations in the macula to combat oxidative stress, which can increase with age, making these antioxidants critical to protecting sight over time.24

Dietary Supplements

The only supplement that demonstrated a protective effect against AMD progression was the AREDS formula.15,33,34 The original AREDS supplement, which contains beta-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc and copper, was beneficial in delaying the progression of late AMD in two reviews.33 It is important to note that high-dose beta-carotene supplements have been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer among individuals who are active smokers.34 The new formulation of AREDS2 added omega-3 fatty acids, lutein and zeaxanthin, and removed beta-carotene.34

Unlike omega-3 fatty acids derived from the diet, MDFA’s findings indicated that omega-3 fatty acid supplements taken in isolation did not protect against the progression of AMD.28 Therefore the advice is to boost fish consumption rather than rely on supplements.

Alcohol

MDFA’s review found that alcohol consumption has a detrimental effect on AMD, with an increased risk of early AMD seen with intake of more than 12 g of alcohol per day.35 Alcohol is a known neurotoxin that can lead to oxidative brain damage and therefore, high amounts may be expected to negatively impact the retina.36 Regular alcohol consumption can also contribute to low-grade chronic inflammation in the body, which is associated with an increased risk of AMD.35,36

The inclusion of the new guidance to limit the amount of alcohol consumed is consistent with National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) advice and aligns with messages to reduce other chronic diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease.37

THE IMPLICATIONS OF THIS WORK

MDFA’s review will help inform community messages on healthy eating.

Dietary recommendations for those who are at risk of developing AMD or progressing to late stages of AMD are summarised in Table 2. These recommendations align with advice of the current NHMRC Australian Dietary Guidelines,38 and reinforce dietary advice for Australians to lower risk of other chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. MDFA hopes these specific eye-health recommendations will be useful for eye health professionals in

Australia, as well as provide evidence-based guidance to community members.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit mieducation.com/new-evidence-on-eatingpatterns-changes-to-amd-nutrition-guidelines.

References available at mieducation.com.au

Dr Kathy Chapman is the Chief Executive Officer of Macular Disease Foundation Australia. She has a Master’s in Nutrition and Dietetics and PhD from the University of Sydney.

Margaret Nicholson is a Senior Lecturer in the Discipline of Nutrition and Dietetics, at the Sydney Nursing School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney.

Laura Baker completed a Master’s in Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Sydney in 2023.

Professor Victoria Flood is Head of Rural Clinical School, Northern Rivers, and Director of University Centre for Rural Health, Northern Rivers, with the Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney. She is an accredited practising dietitian, and was a chief investigator on the Blue Mountains Eye Study.

Victoria Heaton is an optometrist employed as a Research Coordinator at Macular Disease Foundation Australia.

Ka Hang Cheong completed a Master’s in Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Sydney in 2023.