mieducation

Ocular Therapeutics in Clinical Practice: The Times, They Are A-Changing

Since the initial recognition of optometrists to be able to prescribe topical agents, there have been several changes to this legislation in Australian states.1 Whatever the occasional changes that have been made, one clear message has always remained: Therapeutic endorsement in optometry has changed the scope of clinical practice in a positive manner. The ripple effect has been a much-needed contribution towards co-management with ophthalmology.

In fact, as Dr Christolyn Raj writes, many clinicians will attest that having prescribing rights has made them more passionate about their work and helped to establish valuable connections with peers that previously did not exist.2,3

WRITER Dr Christolyn Raj

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand how to safely practise within the therapeutics guidelines,

2. Understand the importance of co-management and the roles and responsibilities of each clinician involved,

3. Develop a protocol to manage patients commenced on medium to long-term medications (topical steroids and antibiotics),

4. Develop an appreciation of why topical treatment alone may not suffice in the management of complex cases, and

5. Understand the need to broaden scope of practice with regards to therapeutics.

As we see our population grow and age, we must be mindful that a knowledgeable and capable team of eye professionals – both optometrists and ophthalmologists – are needed to support the complex needs of our patients.

The key to success of therapeutic endorsement lies with the robust way in which it was initially rolled out, a protocol used both in Australia and the United Kingdom.4 Independent prescriber training requires the completion of didactic learning modules, a period of clinical placement under the supervision of a designated ophthalmologist, and a final examination. While this is incorporated into the curriculum for today’s graduating optometrist, it is an additional continuing education task for the already qualified optometrist.

The challenge for both young graduates and experienced clinicians then becomes putting this clinical learning into day-to-day practice. It is a challenge that is somewhat underestimated.

While short clinical placements may be adequate for understanding key learning concepts, is it enough to prepare the clinician to manage any case that presents?

In my opinion, the best learning is still done in your day-to-day practice and as many of you will appreciate, this style of learning is undefined and often infinite.

The objectives of this article are to empower you to look at key features of therapeutic prescribing including:

1. What should co-management look like?

2. How do we safely navigate the therapeutics landscape, being mindful of common ‘traps’ we may encounter?

3. What can we do in our practices to enhance our learning in therapeutics?

EMBRACING EMPIRICAL TREATMENT

Empirical treatment is defined as treatment, in this case with topical agents based on best known evidence and experience without having precise knowledge about the aitiology.5 Empirical treatment regimens are frequently used in initialising management of a variety of eye conditions, ranging from microbial keratitis to anterior uveitis.

The reason for empirical treatment is to prevent delay in management in an attempt to improve the visual prognosis. However, this does not always mean that commencing a steroid early, or using multiple antimicrobial preparations, are optimal treatment. It merely references that there may be a role for judicious and safe use of topical agents in certain circumstances.

CAVEATS TO EMPIRICAL TREATMENT

In the case of acute anterior uveitis, aggressive yet cautious use of steroids can help to mitigate sequalae, however the type of topical steroid – and the dosage and frequency chosen – is dependent on multiple factors including patient age, severity of the presentation, anterior or posterior uveitis, and other ocular co-morbidities. A ‘one size fits all approach’, even in the initial management of this common condition, is unlikely to yield promising results.

For example, a 25-year-old healthy male, presenting with his first episode of anterior uveitis with mild anterior chamber reaction, Snellen best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/6, and intense photophobia, would do well with initial treatment involving Prednefrin Forte (prednisolone acetate 10 mg/mL (1%) and phenylephrine hydrochloride 1.2 mg/mL (0.12%)) every two hours and a weak cycloplegic agent, such as cyclopentolate 1.0%, twice a day. The concerns here are a rapid steroid response and the long-term side effects of steroid use should he require a long taper. Therefore, careful use of a well-penetrating steroid agent, used with adequate frequency for a short period, should be enough to treat the uveitis while limiting iatrogenic side effects.6

A

B

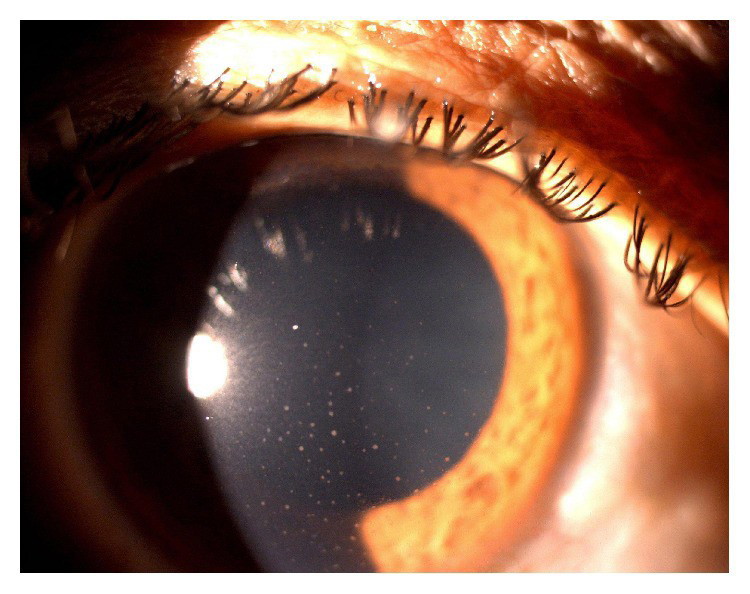

Figure 1. A) Anterior uveitis showing cells and flare within slit lamp beam. Reproduced from: Gogri, P.Y., Misra, S.L. et al., under Creative Commons licence, B) With posterior involvement: cystoid macula oedema (CMO).

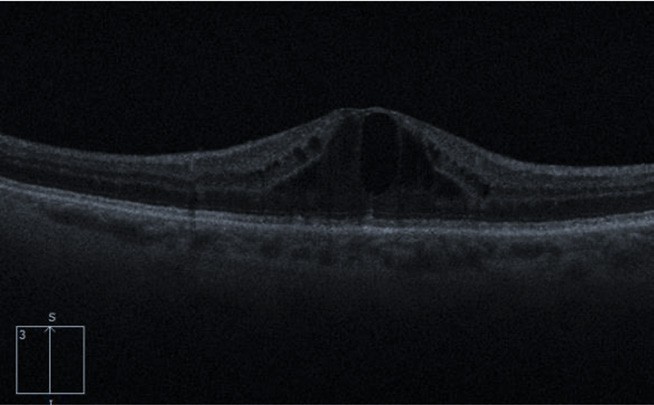

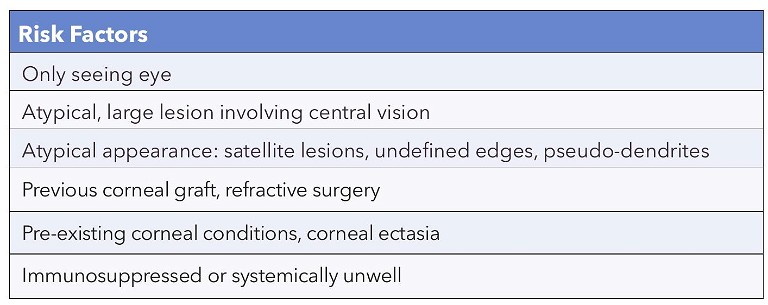

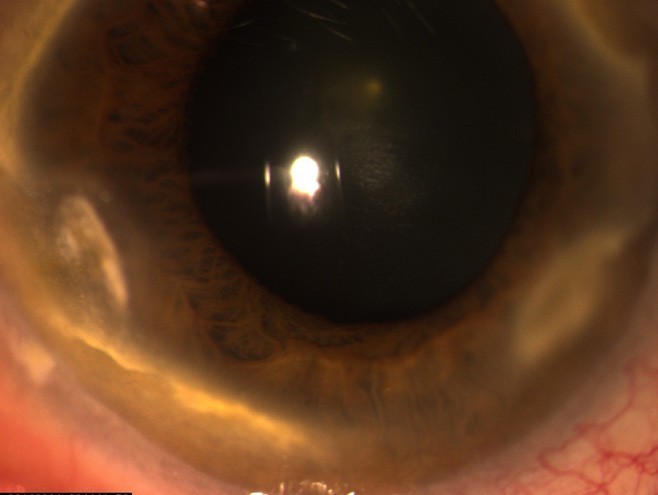

Figure 2. Infectious keratitis in a non-contact lens wearer.

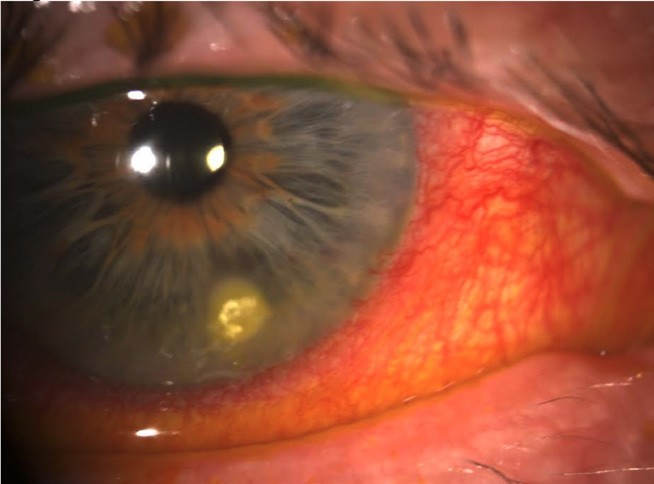

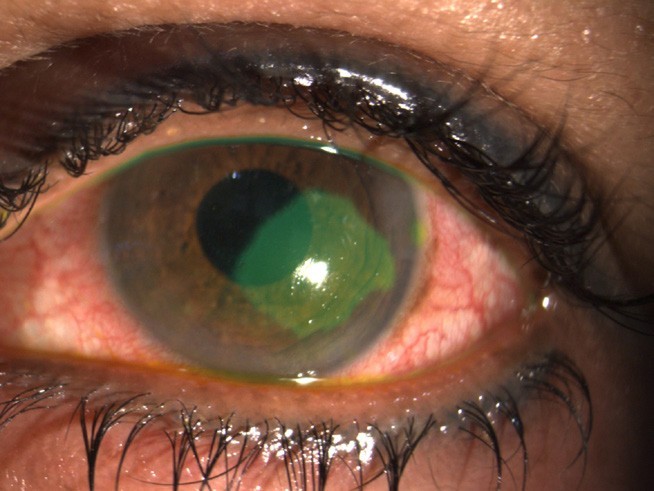

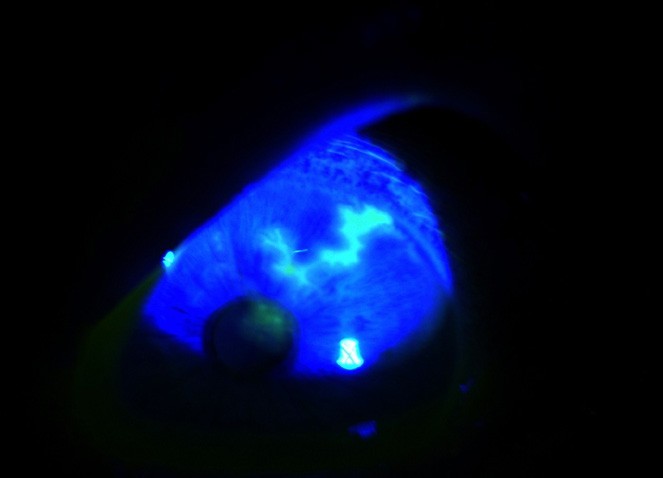

Figure 3. Infectious keratitis in a patient with a previous corneal graft.

However, if the above case example presented with posterior involvement in the form of cystoid macula oedema (CMO) and significant reduction in BCVA (Figure 1A and 1B) the therapeutic management would significantly differ. In this case, it would be wise to consider an early referral to ophthalmology. While there is a small role for topical steroids here, they would need to be augmented initially with a periocular or orbital floor steroid such as triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/ml.7

In yet another example, this time of relapsing anterior uveitis in a 50-year-old female with severe anterior segment inflammation, including fibrin formation, posterior synechia, and reduced BCVA, a more aggressive initial treatment plan would be required. It would be advisable to consider a stronger topical steroid, such as Maxidex 0.1% (dexamethasone) hourly, including a loading dose quarterly in the first one to two hours. A cycloplegic agent, such as atropine sulphate 1%, would be necessary here to break new iris synechia, although this will not affect pre-existing synechia.8 In addition, all cases of relapsing uveitis are best comanaged early as they mandate a thorough systemic work up, including investigation of underlying inflammatory and infectious causes. Close follow-up for sequalae, such as secondary glaucoma, cataract, and maculopathy, is also required.

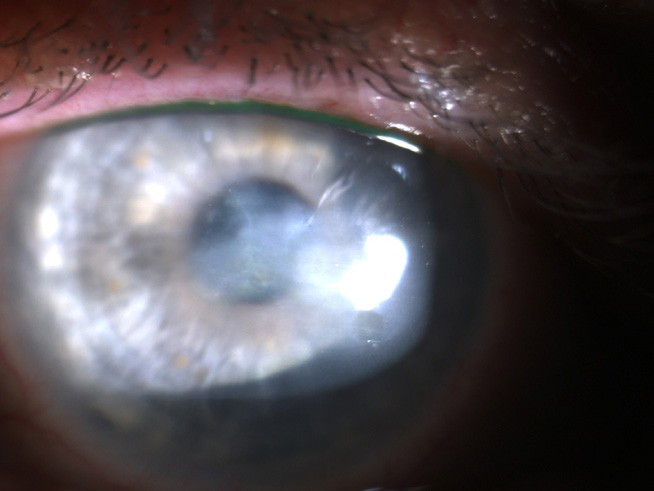

Table 1. Risk factors challenging empirical treatment in infectious keratitis.

SAME DISEASE PROCESS, DIFFERING INITIAL MANAGEMENT

While the management of uveitis may be complex, even in the most routine presentations, it is not alone. Another commonly presenting condition is microbial keratitis. Over the past decade, the incidence of infectious keratitis has remained stable, despite improvements to contact lens wear. The reasons for this are likely related to a steep increase in soft contact lens wear alongside unregulated access.9,10

Empirical treatment in microbial keratitis can be vision saving but, once again, there are caveats. Figure 2 shows typical infectious keratitis in a non-contact lens wearer. There is a circular infiltrate measuring 2 mm in diameter with an overlying larger epithelial defect of 4 mm in the inferior cornea. There is a circumferential ciliary flush but no anterior chamber reaction. From clinical appearance alone, without a corneal scrape, it is impossible to determine the causative infectious agent. However, an empirical topical regimen of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as Ocuflox (ofloxacin 0.3%) used hourly upon waking hours, is a sensible initial approach. Further adjuvant therapy with a cycloplegic agent, such as cyclopentolate 1.0% for analgesia twice daily and preservative free lubricants two hourly, would also be advisable. In this case, improvement would be expected within 48 hours and a daily review would be prudent.

However, there are other presentations of infectious keratitis where the above empirical treatment may be challenged. Figure 3 depicts a similar microbial keratitis in an eye that has previously undergone corneal grafting. This case shows that the suspicious area overlies at least two corneal sutures, increasing the risk of endophthalmitis. In this setting, a corneal scrape will be vital to the ongoing management and needs to be done first, prior to initiating any treatment. An early referral here is warranted and initial treatment may be done with alternative topical agents such as fortified gentamicin 8 mg/ml eye drops.11 Other circumstances where empirical treatment of infectious keratitis should be reconsidered are summarised in Table 1.

EMPIRICAL TREATMENT IN NON-VISION THREATENING PRESENTATIONS

In my experience, non-vision threatening case presentations are more symptomatic due to pain or inflammation rather than infection. However, we need to be mindful of treating these symptoms without increasing the risk of iatrogenic infection.

Figure 4 shows a corneal superficial epithelial erosion day one following routine cataract surgery. The corneal erosion is superficial and will heal over 24–48 hours. The most concerning issue is secondary infection in the setting of recent cataract surgery. The aim in empirical treatment here is to promote epithelialisation which is best achieved with intensive preservative free lubricants and replacement of bacteriostatic antibiotic such as Chlorsig (chlorampehenicol 5 mg/ml 0.5%), routinely used in the post-operative period, with a bactericidal agent such as Ocuflox.

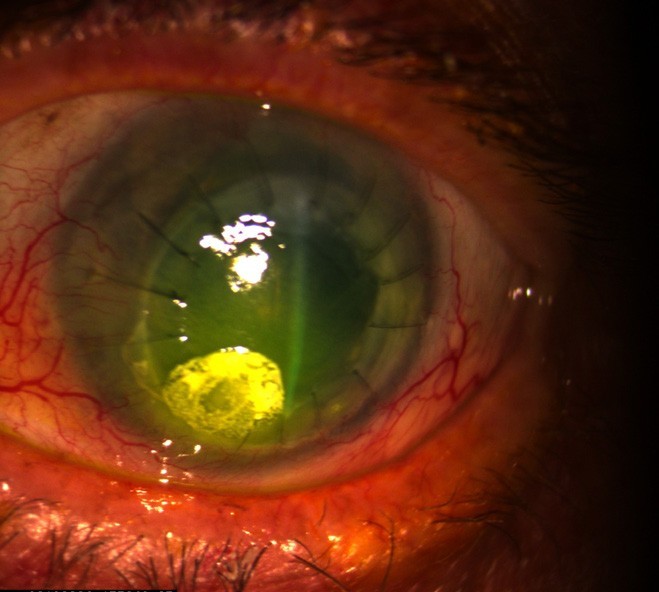

In the case of an inflamed pinguecula (shown in Figure 5), an appropriately selected topical steroid with adequate episcleral penetrance such as Flarex (fluorometholone acetate 0.1%) or non-steroidal agent such as Acular (ketorolac) can be sufficient if used three to four times a day over a 10-day period. This will allow ease of tapering and is unlikely to have unwanted side effects, such as a sudden rise in intraocular pressure (IOP).

Figure 4. Corneal epithelial abrasion on day one following routine cataract surgery.

Figure 5. Inflamed pinguecula.

LET’S TALK ABOUT STEROIDS

We alluded to the judicious use of steroids in the cases presented so far. So, what does this really refer to? In my opinion, the key to effectively employing steroid use in your day-to-day practice is experience.

The main questions we should be asking ourselves when considering prescribing steroids are when is the ideal time to commence topical steroid treatment and what adverse events could occur?

Both these questions can be well answered using corneal keratitis as an example. In the case of herpetic keratitis (herpes simplex virus (HSV ), Figure 6), we know that topical steroid use too early can exacerbate the underlying virus and worsen the keratitis. The HEDS study gives us good guidelines on the use of steroids and advises that use of steroids even 10 days following topical antiviral treatment is useful to prevent stromal scarring.12 In addition, a steroid agent with good penetration into the corneal stroma (Prednefrin Forte rather than Flarex) is advisable. Figure 7 shows a case of HSV keratitis with significant stromal scarring where there may have been some delay in using steroids.13 Figure 8 depicts a case of chronic marginal keratitis where the type of steroid prescribed initially was likely too weak for effective corneal penetration, now resulting in widespread stromal scarring. Once again, while in this condition, it is generally advocated that a weaker steroid such as Flarex may be sufficient. In certain cases of aggressive disease, there is a need to ‘up the ante’ with a stronger agent such as Maxidex or Prednefrin Forte.

THE ART OF TAPERING

All patients respond differently to medications in general, and topical steroids are one such medication with a variable response. However, there are some guidelines that can assist us. We know that steroidinduced rises in IOP often occur in the four to six week period after commencement of the steroid, and are much more likely in younger patients, high doses, and long duration of treatment.14 For this reason, it is often safer to treat with a sharp, short burst of a potent topical steroid rather than a protracted course of a weaker agent.

The use of a more potent agent means that we can begin tapering the steroid quite early. Tapering a steroid is essential to limit the proliferation of immature inflammatory cells, which can result in rebound inflammation. For this reason, I like to consider tapering for longer than the duration of intensive treatment. For example, in a case of typical anterior uveitis, my tapering regimen involves two hourly for five days; then four times a day for one week; twice a day for one week; then daily for one week.

WHEN TREATMENT IS NOT WORKING

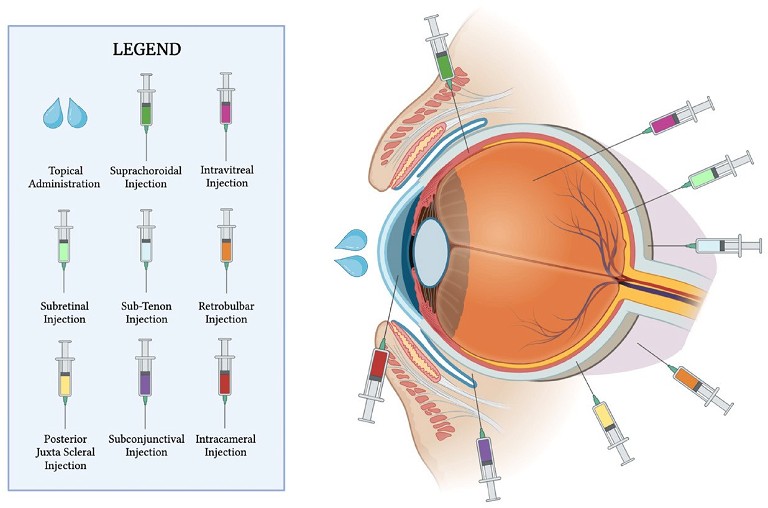

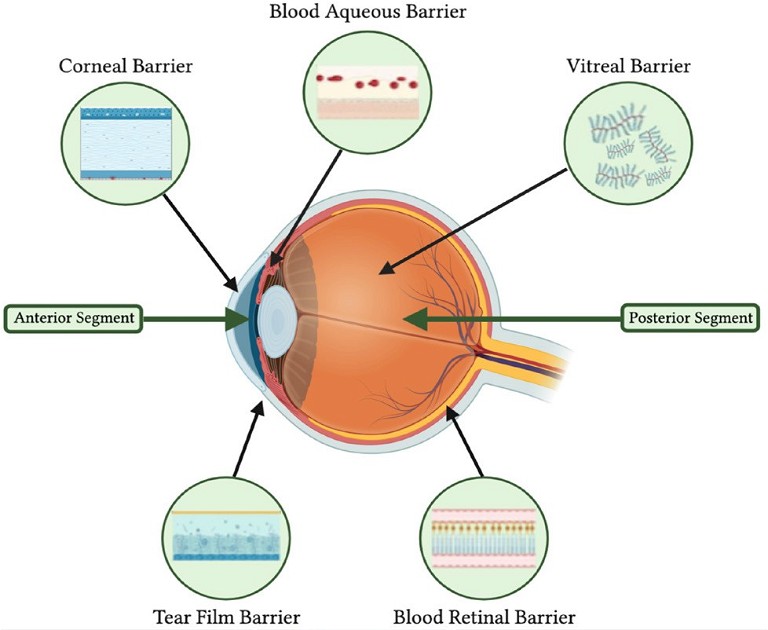

We must remember that topical agents are just one arm of ocular therapeutics.

With the complexity of ocular conditions, even those that seem to initially present with typical signs may not respond to routine treatment.

As shown in Figure 9A, there are various methods of drug delivery into the eye. The main reason for this is the unique anatomy of the ocular structures and specific barriers that need to be overcome for a drug to be effectively delivered to a site (Figure 9B).15 This means that quite often we may need to employ more than one of these modalities to achieve remission of a condition.

This is where it is helpful to work within a collaborative network of peers, so support is available when initial first line topical treatment is not achieving the desired results.

Figure 6. Typical branching dendrite in epithelial herpes simplex keratitis.

Figure 7. Extensive central corneal scarring from HSV stromal keratitis.

Figure 8. Extensive peripheral corneal stromal scarring from marginal keratitis. (Figures 2–8 reproduced with permission from Dr Lewis Levitz, 2023).

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN FOLLOW-UP

It has become commonplace in my practice, whenever I am prescribing any topical agent, to ask myself “when should I see this patient again?”.

This is something that is often influenced by factors that are outside of our control, including patient access issues and appointment availability, as well as the patient’s understanding of the seriousness of their disease. When constructing a follow-up plan, as clinicians, we need to steer clear of this complicating factor and think scientifically. Some simple rules for optometrists to consider include:

• If using topical steroids, always review the patient at one week,

• Educate your patient to report any vision changes within 24 hours,

• If treating an infection, consider a review in 48 hours, and

• If atypical features or a sub-optimal response to treatment is seen at the first follow-up, consider early referral to ophthalmology.

WHERE TO FROM HERE?

Optometrists have certainly weathered the storms in the long road to achieving prescribing rights, however there is still some evolution required. The focus now should be on safeguarding these rights by maintaining safe clinical practice.

We are all improving our practice daily, part of which involves challenging ourselves in our clinical work. This may look different for each of us.

For some, it may help to broaden our scope of practice to enhance our patient base and obtain a richer experience in prescribing. Perhaps consider co-management of postoperative cases with an ophthalmologist or consider delving into the area of contact lenses or dry eye disease, or even carve out some time in your clinic sessions dedicated to semi-urgent or ‘red eye’ consults. It will certainly assist in increasing your comfort levels with prescribing, and broaden your knowledge base of ocular disease.

Another valuable exercise is to organise regular peer review to share experiences, offer constructive feedback, and discuss interesting cases with a learned colleague. This may not always be practical to do face to face but we can still achieve this virtually by organising a regular forum over an online platform. Even establishing a dedicated peer group network on a private messaging app like WhatsApp or Signal, where you can communicate or discuss with other clinicians in real time, can be instrumental in both teaching and learning.

So, consider making some adjustments like this to enhance your clinical acumen while exercising your current prescribing rights. Perhaps it may even motivate you to take on further clinical challenges. Above all, you will find it satisfying: your greatest reward will come from your grateful community of patients.

Figure 9. A) The various modalities of ocular drug delivery.

B) Anatomical barriers within the eye that play a vital role in drug delivery.15 Reproduced under Creative Commons licence.

“ Optometrists have certainly weathered the storms in the long road to achieving prescribing rights… The focus now should be on safeguarding these rights ”

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit: mieducation.com/ocular-therapeutics-in-clinicalpractice-the-times-they-are-a-changing.

References 1. Milestones in Australian Optometry: Available at optometry.org.au/national_state_initiatives/medicare-a-highlight-in-100-years-of-milestones. Accessed 28 July 2009; Last updated 2018.

2. Roth, M., Optometry in Australia is a therapeutic profession, Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2007; 90:67–69. DOI: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2007.00129.

3. mivision, The pull of therapeutic endorsement, 19 Nov 2023, available at: mivision.com.au/2023/11/the-pull-of-therapeutic-endorsement [accessed May 2024].

4. Bolland, S., Henderson, R., Loffler, G. et al., Therapeutic prescribing for optometrists: an initial perspective, Optometry in Practice. 2011;12:3 87–98.

5. Leekha, S., Terrell, C.L., Edson, R.S., General principles of antimicrobial therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Feb;86(2):156– 67. DOI: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0639.

6. Bartlett, J.D., Anti-Inflammatory Agents. In: Ophthalmic Drug Facts. St. Louis: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2005:87–99.

7. Cunningham, E.T. Jr, Wender, J.D., Practical approach to the use of corticosteroids in patients with uveitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45:352–8. DOI: 10.3129/i10-081.

8. Babu, K., Mahendradas P. Medical management of uveitis – current trends. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jun;61(6):277– 83. DOI: 10.4103/0301-4738.114099.

9. Dart, J.K.G., Radford, C.F., Minassian, D. et al., Risk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: a case-control study. Ophthalmology 2008;115: 1647–1654. e1643. DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.05.003.

10. Efron, N., Morgan, P.B., Jones, L.W., et al., All soft contact lenses are not created equal, Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2022 Apr;45(2):101515. DOI: 10.1016/j.clae.2021.101515.

11. Gokhale, N.S. Medical management approach to infectious keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008 May–Jun;56(3):215–20. DOI: 10.4103/0301-4738.40360.

12. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jul 30;339(5):300–6. DOI: 10.1056/ NEJM199807303390503.

13. Leibowitz, H.M., Kupperman A., Uses of corticosteroids in the treatment of corneal inflammation. In Leibowitz, H.M. (ed.) Corneal Disorders, Clinical Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1984:286–307.

14. Cakanac, C., Topical steroids 101. Here’s a refresher course on the science and clinical use of this class of potent anti-inflammatory drugs. Review of Optometry, April 2005, available at: reviewofoptometry.com/article/topical-steroids-101 [accessed May 2024].

15. Wu, K.Y, Tan, K.,Tran, S.D., et al., A new era in ocular therapeutics: advanced drug delivery systems for uveitis and neuro-ophthalmologic conditions. Pharmaceutics 2023;15(7):1952. DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071952.

Dr Christolyn Raj MBBS (Hons) MMED MPH FRANZCO is a Melbourne-based ophthalmologist. Dr Raj is a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) and the American Association of Ophthalmologists.

Dr Raj is an examiner for the Australian College of Optometry Ocular Therapeutics course. She is also involved in comanagement with therapeutic-endorsed optometrists in her clinical practices: Vision Eye Institute Camberwell, Blackburn, and Coburg. Dr Raj also educates ophthalmology trainees as a RANZCO examiner, clinical tutor, and mentor. Her dedication to teaching continues with her affiliation with The University of Melbourne as a Senior Lecturer, where she oversees medical student teaching.