mifeature

Working with

Neurodivergent Children

Neurodivergence is a term which ”describes people whose brain differences affect how their brain works”.1 As Adelaide orthoptist Natalie Ainscough writes, a very different approach is required when a neurodivergent child is in your chair.

WRITER Natalie Ainscough

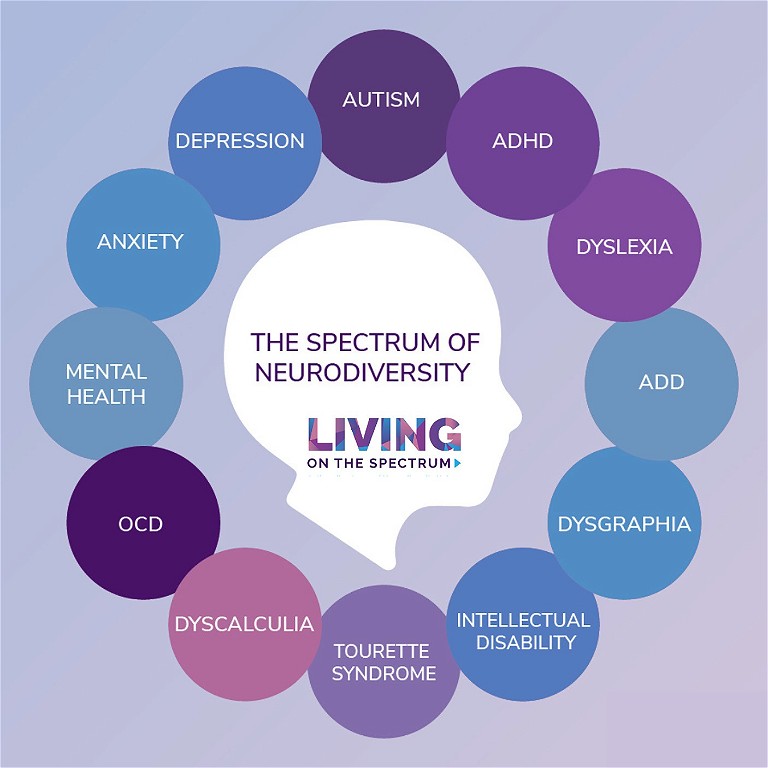

The term ‘neurodiverse’ encompasses a group of patients including those suspected to have, and diagnosed with; autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), attention deficit disorder (ADD), intellectual disability (ID), as well as eight other conditions.

The most commonly diagnosed is ASD, affecting 0.7%, or about one in 150 people in Australia.2 Overlapping of neurodivergent conditions is also common; with 15–79%3 of the population having more than one formal diagnoses, depending on the type of tests undertaken, definitions used, and study methodologies.

A fantastic resource has been developed by Living on the Spectrum, an Australian based group that has a directory of neurodivergentfriendly professionals and resources. Its graphic, representing the 12 conditions that come under the banner of ‘neurodivergence’ (Figure 1), is a helpful visual representation for all professionals working alongside those with these conditions.

Most neurodivergent children require a very different approach to the eye examination to allow them to complete it successfully, this means reconsidering how we conduct these types of appointments.

This is a very simple statement to make, but what does it actually mean in the dayto-day clinical environment?

TAKE A BROADER LOOK

As an orthoptist, I have spent 15 years working in both public health and private clinics with a significant paediatric focus throughout that time, culminating in working at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide for the past decade and co-owning a private practice.

This article outlines some areas of consideration for those working with neurodiverse patients, breaking down what can be easily adapted to enable success. I want to stress that neurodivergent patients have wide-ranging and varied needs, so I have focussed on the most common areas of overlap in the eye clinic.

WAITING AREA

Providing a quiet and calm waiting space for the patient and their family is a great start. This could be an unused consulting room, or a dedicated quiet waiting area. Quiet spaces are not just about general noise, they are also about minimising visual noise and should be in low traffic areas. This means keeping the space relatively sparse, no busy patterns on the carpet, no clutter, and bins should be out of easy reach.

Other waiting room bonus options include the ability to adapt lighting levels, a TV that can be controlled by the family, and free Wi-Fi access for them to watch videos, play games or listen to their own music to keep them calm and entertained. Having an accessible charging point for their tablet/ phone etc. can be a useful touch.

If there is a delay in seeing the patient, let the family know as soon as possible; they may choose to go for a walk, or sit in the car, and return later, to prevent the child getting anxious or restless.

Toys are great, but need to be cleaned, maintained, and stored. Families will often bring what they need with them.

CASE HISTORY

As a clinician meeting a neurodiverse patient for the first time, it is important to understand the severity of their diagnosis, any co-existing diagnoses, their family history as well as the parents’ overall impression of their child’s eye sight, eye alignment, and movement. The earlier the child is diagnosed with a type of neurodivergence, the more severe it is likely to be, so it’s worth knowing when it was first raised as a possibility and then when the formal diagnosis was made. Noting that the average age for formal ASD diagnosis overseas is four to five years of age,5 many children will attend initial eye examinations prior to diagnosis, but strong suspicions may exist.

Considerations should include: Should the child be old enough to be in an education setting; have the teacher or support workers raised any concerns? How are they doing at school? What tasks are being focussed on in school currently?

For those also undergoing adjacent therapeutic intervention, such as speech and language therapy (SaLT), physiotherapy or occupational therapy (OT), it is also worth asking whether there have been any concerns around eyes in those sessions. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has an active early intervention pathway for children under seven, meaning that suspected and diagnosed neurodivergent children will likely have a range of therapies being undertaken to assist their development that can provide useful input.

Figure 1. The 12 conditions that come under the term ‘neurodiverse’. Graphic courtesy of Living on the Spectrum.4

VISION TESTING CHALLENGES

It is so important to not make assumptions about a patient’s ability, simply based on a neurodivergent diagnosis. Many can perform formal visual acuities with adaptations. The key is to rapidly modify testing protocols to make the tests accessible prior to the child using up all of their concentration on the ‘wrong’ test.

Taking a few extra minutes to understand the child prior to commencement of vision testing can really pay off when it comes to successful interactions. This requires a combination of observation, and communication with the patient and their parent. The following should be considered:

• Will this child sit in the assessment chair alone?

• Will they sit there for long?

• Can this child perform an age-appropriate visual acuity test? Or do they need something different?

• What optotypes are they comfortable with? This may mean using something slightly easier that they can realistically manage, but increasing the visual complexity to better detect amblyopia or refractive error. For example, doing a multilinear Lea logMAR vs linear HOTVX logMAR.

• Will they be able to perform this uniocularly, or would it be best to start with binocular testing to gain their confidence?

Always document which eye is tested first, as you may need to alternate which eye you test first at each visit if the child tends to lose concentration. In cases where you have a confirmed amblyopic, or reduced vision eye, always test that one first to ensure you obtain at least that reading.

Some children will only do one eye visual acuity tests each visit for a while; that is ok. Adapted testing allows success to be gained, and it may take up to three visits to get the full initial assessment.

When patients have speech delays that prevent a standard approach to visual acuity testing based on their age, I assess their ability to perform work-around tests by asking questions such as:

• Do they play matching games?

• Do they know the name/sound of the pictures on a matching card?

• Are they learning to sign to support their language development? If so, can they sign some of the picture optotypes?

• Are they using a Pragmatic Organisation Dynamic Display (PODD)? If so, can we add any of the optotypes relevant to testing to the device? PODD devices are increasingly being funded by NDIS for pre-school age children, and it can be quick to add new buttons for vision testing.

If it’s not easy to do then and there, can you provide copies of the optotypes to parents, to be added to the device for next time?

TIMING

Timing of appointments is one of the simplest adjustments to make for this group of patients. Many children have a ‘best’ time of the day. This is amplified for those on the spectrum and can be the difference between success and failure during testing.

• Do they generally do better in the morning or afternoon?

• I never recommend seeing neurodiverse children after school, they are generally tired and less able to push through low levels of anxiety under these circumstances.

• Do they take any behaviour modifying medications such as Ritalin (methylphenidate)? This is prescribed in some children with ADD and ADHD. If so, I suggest the appointment be scheduled for one to two hours after a dose.

“ If someone is prone to generalised anxiety, books and videos about eye clinic visits can be extremely beneficial ”

MENTAL HEALTH

A lot of younger patients with a diagnosis of neurodiversity may also have overlying social anxiety or generalised anxiety that has not yet been specifically diagnosed. Parents and carers are often able to provide advice as to what their child experiences; this fits in directly with knowing whether someone is a sensory seeker or avoider.

If someone is prone to generalised anxiety, books and videos about eye clinic visits can be extremely beneficial.

Parents can prepare children prone to anxiety by explaining what is happening in advance, showing them books about eye clinic visits, or even videos of your eye clinic.

SENSORY SEEKING VS SENSORY AVOIDING

This, in itself, is its own topic, but many ASD children will either be sensory seekers or avoiders. Knowing whether a child has these tendencies (and what triggers them) can again allow you, as the clinician, to ensure you are working in an environment that is conducive to the patient’s needs.

Those who are sensory avoiders are more challenging when undertaking an eye assessment, as they are more likely to struggle with occlusion for vision testing, removing or wearing glasses, reacting negatively to bright torches/slit lamp/ophthalmoscope, be averse to noises from toys and equipment, and overall be non-tolerant to the proximity required for testing.

These are the patients that benefit the most from preparation, quiet waiting areas, shorter waiting times, and a more ‘gentle’ style of assessment spread over a few appointments if required. Giving them the ability to touch and feel fixation targets, toys, equipment etc. can be of great help to them, and reduce their overall anxiety.

Consistency of care and, therefore, clinical approaches, also plays a huge role in helping the patient know who and what to expect on return appointments.

CONCLUSION

The challenge of working with neurodivergent children is one of the things I enjoy most about my role. Knowing how to adapt your testing approach rapidly based on the patient in front of you, while still having an eye to good clinical assessment, is a skill learnt over time.

By working collaboratively with their parent/carer, you can often successfully assess the neurodivergent child in a way that parents or carers did not expect could be done. Not only will the patient and family be over the moon at the child’s success, they will likely be lifelong patients of your practice due to the different approach you provided them with.

Natalie Ainscough BSc (Orthoptics) MMedSci (Vision and Strabismus) is the Orthoptic Clinical Coordinator at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide and co-owner of Adelaide Orthoptics. She has been working as an orthoptist since 2008, moving to Australia in 2023.

Throughout her career she has had a strong focus on paediatric and neuro-ophthalmology.

References

1. Cleveland Clinic, Neurodivergent (webpage, last reviewed June 2022) available at: my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent [accessed 20 November 2023].

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Autisum in Australia (web report, last updated 5 April 2017) available at: aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/autism-in-australia/contents/autism [accessed 20 November 2023].

3. Curnow, E., Rutherford, M., Meff, T., et al., 2023. Mental health in autistic adults: A rapid review of prevalence of psychiatric disorders and umbrella review of the effectiveness of interventions within a neurodiversity informed perspective. Plos one, 18(7), p.e0288275.

4. Image from Living on the Spectrum, The spectrum of Neurodiversity – The meaning (webpage, updated 21 March 2022) available at: livingonthespectrum.com/education/the-spectrum-of-neurodiversity/ [accessed 30 November 2023].

5. Zwaigenbaum, L., Bauman, M.L., Kasari, C., et al., 2015. Early identification of autism spectrum disorder: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics, 136(Supplement_1), S10–S40.