mieducation

Keratoconus:

Detection and Management

Keratoconus has a prevalence of up to one in 84 people in the Australian population. Understanding the tips for early diagnosis, the management required at diagnosis, appropriate information for a thorough referral, and the numerous treatments available is important for such a common disease.

WRITER Dr Brendan Cronin

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand the incidence of keratoconus in the Australian community,

2. Appreciate why certain information in the referral can assist in accessing faster treatment,

3. Know how to screen for the disease with autorefractors and a retinoscope,

4. Understand the many surgical treatment options, and

5. Understand how glasses and contact lenses can be used to manage the disease.

WHAT IS KERATOCONUS?

Keratoconus is an inflammatory corneal disorder that affects up to 1.2% of the Australian population.1 A family history of keratoconus, ocular allergies, and eye rubbing are the largest risk factors for developing the condition. Given the significant lifelong visual complications associated with the disease, there is enormous public health benefit in early diagnosis and treatment. Thankfully, we now have treatments that not only halt the progression of keratoconus but can provide excellent visual outcomes without traditional full thickness corneal transplants.

IDENTIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The characteristic symptoms of keratoconus are reduced visual acuity and increased sensitivity to light and glare, particularly flaring of lights at night. Optometrists have always been particularly adept at identifying patients with these symptoms, along with reduced best-corrected spectacle acuity, especially in the context of increasing astigmatism.

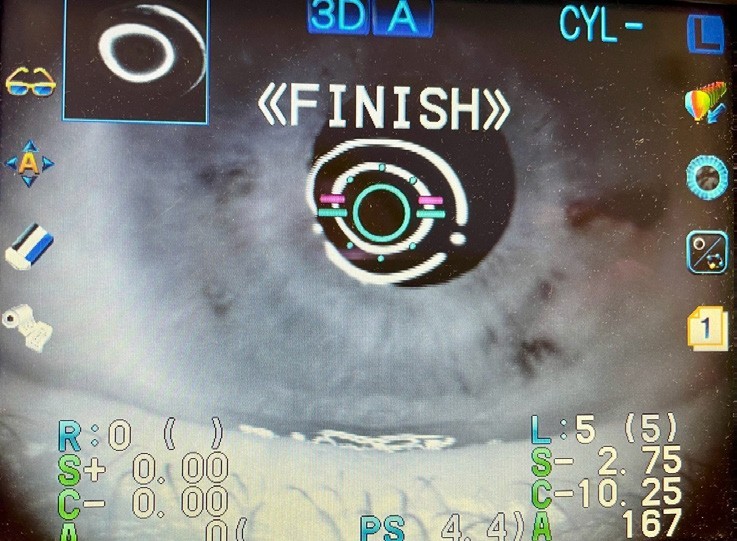

Clinical techniques, such as the scissor reflex or the Charleaux/oil droplet sign on retinoscopy can be diagnostic of the condition, but modern equipment makes the diagnosis much easier. Distorted mires on autorefraction, or an autorefraction that is significantly different to the subjective refraction, are both good diagnostic indicators.

Placido disc-based topographers are commonplace in optometry practices. This makes a definitive diagnosis of keratoconus routine. Combining this with corneal and sometimes epithelial thickness measurement from optical coherence tomography (OCT) machines can yield a very high sensitivity in detecting and diagnosing keratoconus and other corneal ectasia disorders. Combined topographers and tomographers can assist in even earlier diagnosis by assessing changes in the posterior corneal curvature, however these machines are much more expensive than placido disc machines.

Corneal biomechanics takes this to an even more advanced level. Instruments such as the Oculus Corvis ST can assist in risk stratifying a patient’s risk of ectasia when the topography may be borderline. New integrated tools minimise information overload by incorporating biomechanics, topography, and tomography into simple diagnostic reports for clinicians.

Considering the prevalence of keratoconus in the Australian community, which is up to one in 84, there is a good argument that all patients under 30 with a new diagnosis of astigmatism should have topography performed if there is a topographer available in the practice.

EARLY REFERRAL MEANS EARLY TREATMENT, BETTER OUTCOMES

Modern treatments for keratoconus not only stop the progression of the disease but can also improve corneal topography, leading to better visual outcomes. Early diagnosis and referral of patients with keratoconus can increase the likelihood of more treatment options being available.

Figure 1: Distorted mires on autorefraction.

It is crucial that children with suspected or confirmed keratoconus are referred for review as the disease can be more aggressive in younger patients.2 Optometrists should not wait to document any refractive, visual, or topographic progression in children or adolescents with keratoconus and should refer them immediately on suspicion of the disease.

Additionally, it is essential to manage any allergic eye disease promptly and to reinforce the critical importance of avoiding eye rubbing in these patients.

WHAT IS NEEDED IN A REFERRAL?

The information that you provide in your referral for keratoconus is critically important in determining how quickly your patient receives treatment for the condition. Not providing certain information can delay a patient’s eligibility for corneal collagen crosslinking and lead to unnecessarily lost vision.

To subsidise cross-linking, Medicare requires some type of objective documentation of progression. Importantly, this does not have to be topographic progression; a deterioration in visual acuity or a documented change in refraction are adequate.3 Including these in your referral facilitates a faster pathway to cross-linking for the patient. If there is no sufficient documentation of progression, then the patient will have to wait until this can be demonstrated before Medicare subsidised cross-linking can be performed. This means that obtaining previous refractions and best corrected visual acuity information, especially if the vision was previously documented as normal, is extremely important. Similarly, if a patient was previously emmetropic but now has significant astigmatism, this will be important for documenting progression.

“all patients under 30 with a new diagnosis of astigmatism should have topography performed if there is a topographer available in the practice”

Despite Medicare allowing refractive changes as evidence of progression, topography and tomography are the gold standard for both diagnosis and follow-up. Historically, clinicians used the K-max (a measure of the steepest point of keratometry) and the central corneal thickness as the two most important markers of ectasia. Thankfully, we now have much more advanced systems for looking at corneal change. K-max can remain the same, despite very significant posterior corneal topographic changes. Similarly, central corneal thickness can remain stable, despite a significant deterioration in other parameters.

The Belin ABCD classification of keratoconus grading is one of the more widely used systems for progression analysis.4 This system analyses changes in:

A – The anterior radius of curvature for a 3 mm zone centred around the thinnest point of the cornea,

B – The posterior radius of curvature for a 3 mm zone centred around the thinnest point of the cornea,

C – The central corneal thickness, and D – Best spectacle corrected visual acuity.

The grading software shows the clinician how different scans deviate from the mean with confidence intervals for the number of standard deviations. This allows clinically significant progression to be detected as early as possible. Essentially, the aim of advanced topographic and tomographic systems is to detect progression before it affects visual acuity. The next generation ABCD software incorporates corneal biomechanics into the algorithm to improve both the sensitivity and specificity of the system.

GLASSES: BETTER THAN THEY USED TO BE

On the simplest level, even spectacle technology has improved for keratoconus. Obviously, glasses have always been first line treatment for mild refractive errors in early keratoconus. Standard glasses only work when there is no significant anisometropia and the best corrected visual acuity remains acceptable.

While certainly not new, Shaw lenses can be used for patients who still have a satisfactory best spectacle corrected acuity but have significant anisometropia. These lenses dramatically reduce aniseikonia, so will allow people with significantly different refractive errors to comfortably wear spectacles.

Some patients who have reduced best corrected vision in traditional glasses may benefit from spectacle lenses that are based on ocular wavefront measurements. Advanced grinding technology now enables lenses to be ground so accurately that instead of using a subjective refraction, the glasses are made with ocular wavefront measurements. This can minimise higher-order aberrations and improve best spectacle corrected visual acuity. These lenses can be particularly useful in people who are not satisfied with their vision in normal glasses but whose vision is not sufficiently compromised for them to feel as though hard contact lenses are warranted to improve their visual function.

CONTACT LENSES: MUCH BETTER THAN THEY USED TO BE

Traditionally, small diameter rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses were the mainstay of contact lens correction of keratoconus. While these lenses were certainly a great advance when they were first introduced, fitting a hard bit of plastic over the most sensitive part of the body was always bound to create issues with patient comfort and tolerability. Design limitations meant they could not be fitted for patients with severe keratoconus. Further limiting their use was the fact that an imperfect fit of small diameter RGP lenses can cause apical scarring on the cornea, leading to a reduction in vision. For these reasons newer contact lens designs and technology have almost completely taken over from traditional small diameter contacts.

The development of scleral lenses has made wearing lenses much more comfortable for patients, and has also enabled optometrists to be able to fit much steeper and more ectatic corneas.

Like newer forms of glasses, advanced manufacturing techniques for scleral contact lenses means that ocular wavefront measurements can now be incorporated into the lens design. While the development of scleral contact lenses has been a revolution in the management of keratoconus, these lenses traditionally only neutralise the distortion and aberration that occurs on the front surface of the cornea. The residual distortion from the posterior cornea will sometimes leave patients wanting better vision than a standard scleral lens will allow. In these instances, scleral lenses incorporating wavefront measurements can be used to try to negate this issue.

Similar advancements have been made in contact lens fitting. Readily available corneoscleral topography and profilometry allows contact lenses to be made with customised landing angles and sagittal depths. These extremely high levels of individualisation and customisation can facilitate the fitting of previously unfittable corneas so that even patients with very steep cones, other complex corneal ectasias, ocular surface conditions, and decentred corneal grafts can achieve high quality vision with minimal higher order aberrations.

AVOIDING CORNEAL GRAFTS

These days it is very rare for a patient to require a full thickness corneal transplant for keratoconus. There are numerous ways to avoid the long-term complications and morbidities associated with this procedure, although it is, unfortunately, sometimes still required.

Despite the advancements detailed above, many patients have a reduction in their visual acuity or quality of life due to issues with wearing contact lenses. New treatment options may be suitable for these patients.

Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking

Corneal collagen cross-linking has been the largest advance in keratoconus management in decades. It has been in widespread use throughout the world for approximately two decades and is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for progressive keratoconus. Cross-linking involves the application of riboflavin (vitamin B2) to the cornea, followed by irradiation with ultraviolet light. There are numerous different protocols for collagen crosslinking, all with different advantages and disadvantages.

One particularly advantageous protocol for keratoconus is topography guided, oxygen enhanced, transepithelial cross-linking. This not only strengthens patients’ corneas to stop progression, but can also improve their topography and vision. The advantage of this procedure is that a very wide range of corneas can be treated as no tissue is removed. There are very few corneas that can’t undergo this procedure. The addition of supplemented oxygen to the cross-linking procedure means that patients can now have corneal collagen cross-linking without having their epithelium removed.5 This makes the procedure more comfortable, and the recovery faster and less painful. The concept of a cornea being ‘too thin’ for cross-linking is very outdated and is really no longer applicable.6 In one recent study, 39% of patients with severe keratoconus gained two or more lines of vision with topography guided, oxygen enhanced, epithelium on cross-linking.7

“Early diagnosis and referral of patients with keratoconus can increase the likelihood of more treatment options being available”

Topography Guided Phototherapeutic Keratectomy

Topography guided phototherapeutic keratectomy (t-PTK ) is another routine procedure for keratoconus. In this procedure, an excimer laser regularisation of the cornea is planned using the patient’s topography. Depending on the corneal thickness, the refraction, and the topography, it may be possible to factor the patient’s refraction into the ablation profile. Generally, these treatments are intended to improve a patient’s best corrected visual acuity, not to improve their uncorrected visual acuity. This is often combined with cross-linking, either due to the patient’s progression or to restore some of the corneal biomechanics that will be removed due to the stromal ablation. Unlike collagen cross-linking, a significant number of corneas will be too thin for this procedure. Importantly, Medicare does not subsidise cross-linking combined with laser when it is used for nonprogressive keratoconus. It will if the laser is being performed on an eye that is progressing.

PTK can also be used to remove corneal scarring that can occur in keratoconus. Obviously, this will not be effective for full thickness corneal scars. However, PTK can be performed with the sole intention of clearing the visual axis of corneal scars, particularly for superficial apical scarring, and in cases where the patient has worn small diameter RGP lenses for a long time. While such procedures would not be designed to improve corneal topography, they may be advantageous in patients with inadequate stromal tissue for a topography guided ablation.

Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments

Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS) is the modern version of the older Keraring or Intacs procedures. CAIRS can sometimes dramatically improve the best corrected visual acuity of patients with quite severe keratoconus. It provides a treatment option where other options would likely be ineffective. CAIRS involves a small section of non-viable lamellar corneal tissue being inserted in a ringshaped corneal pocket. This quick day surgery procedure can produce significant flattening and regularisation of the cornea with corresponding improvements in vision. CAIRS is a sutureless and painless procedure. Patients can generally return to full activity within a few days.

CAIRS differs from Kerarings and Intacs because the older procedures used corneal ring segments made from plastic, whereas CAIRS uses non-viable corneal tissue. Plastic ring segments need to be inserted very deep into the cornea to avoid potential extrusion. This limits their effect on the anterior surface of the cornea. While plastic ring segments have helped to visually rehabilitate many patients over the years,8 CAIRS is likely to become a more widely adopted technique. CAIRS segments are inserted much more superficially into the cornea as extrusion is not a significant issue. This means there is generally, but not always, a more pronounced effect on the anterior corneal topography. Further, CAIRS segments can be used in patients with thinner corneas than is possible with plastic segments. This makes the procedure a possibility for a wider range of patients.

Combination Treatments

Like all treatments for a disease such as keratoconus, it is important that patients are aware that sometimes a combination of treatments will be able to achieve a far better outcome than any individual treatment alone. For example, sometimes a patient may be a good candidate for a topography guided PTK combined with corneal collagen crosslinking, however the ablation profile might leave the patient with a significant refractive error and anisometropia. In these cases, once the refraction has stabilised, they may be able to have an implantable collamer lens – either to obtain emmetropia or to equalise the refractive error between the eyes to resolve any problematic anisometropia.

Similarly, a patient who has had CAIRS may have had a dramatic improvement in their corneal topography but still have some irregular astigmatism and higher order aberrations affecting their vision. In these cases, a topography guided PTK can be performed after CAIRS to smooth out the residual corneal aberrations affecting the patient’s vision. This combination maximises the regularisation of the patient’s cornea while minimising the amount of stroma ablated to achieve a good visual outcome.

MANAGING HYDROPS

The best management of corneal hydrops is to avoid it! Unfortunately, although rare, it does still happen. It is characterised by a sudden and significant swelling of the cornea due to the leakage of fluid into the corneal stroma from a break in Descemet’s membrane. The condition leads to a rapid decrease in visual acuity and significant discomfort for the patient. Treating corneal hydrops requires a multifaceted approach that aims to stabilise the cornea, alleviate symptoms, and improve visual function.

Conventional treatment for hydrops has been to keep the eye comfortable with a bandage contact lens (if one will fit), topical antibiotics as infection prophylaxis, steroids to reduce inflammation, hypertonic saline to reduce the oedema (not if there is a bandage contact lens in place), and cycloplegia to reduce ciliary spasm.

If the hydrops is away from the visual axis, then a patient may have an excellent visual recovery, as any stromal scarring is likely to be away from the central cornea. If the hydrops involves the visual axis, then the patient is likely to require a full thickness corneal transplant (discussed over the page) for full visual rehabilitation. The aim of early management is to keep the patient’s eye comfortable and uninflamed. Performing a transplant on an inflamed eye can lead to an increased risk of graft failure and rejection, so topical steroids in the early stages of hydrops can facilitate faster surgery.

Some surgeons advocate for earlier surgical intervention in hydrops.9 Administration of intracameral air or longer acting gasses, potentially combined with manually unfolding any retracted Descemet’s membrane and endothelium can sometimes lead to much faster resolution of corneal oedema and avoid the resultant corneal scarring. The downside of intracameral gases is that they may accelerate cataract formation and potentially cause a pupil block and acutely raised intraocular pressure.

Figure 2: Topographic change map showing over 20 dioptres of corneal flattening post CAIRS.

Overall, the treatment of corneal hydrops in keratoconus requires a personalised approach based on the severity of the condition and the individual patient’s needs. Early intervention, regular monitoring, and a combination of conservative measures and surgical options can help manage the condition, improve visual acuity, and enhance quality of life for individuals with corneal hydrops.

“It is crucial that children with suspected or confirmed keratoconus are referred for review as the disease can be more aggressive in younger patients”

WE STILL NEED CORNEAL TRANSPLANTS

Sadly, despite all the advancements in halting the progression of keratoconus and the developments in detecting the disease, we still see patients with severely scarred and thin corneas as well as cases of acute corneal hydrops. In these cases, more significant corneal transplants may still be required.

In cases where Descemet’s membrane is still intact, (this is not the case in corneal hydrops), then a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), may be possible. DALK has the advantage of replacing all of the patient’s stroma without removing the Descemet’s membrane or endothelium. As endothelial rejection and failure are the primary long-term issues associated with full thickness transplantation, DALK avoids these complications. Unfortunately, if a patient has had corneal hydrops, then Descemet’s membrane will have been ruptured and a DALK will not generally be possible. Like a penetrating keratoplasty, DALK requires sutures to be in-situ for 12 to 24 months.

Penetrating keratoplasty involves removing the entire thickness of the patient’s cornea and replacing it with a full thickness corneal transplant. The transplanted tissue is then sutured into the host cornea. Generally, these stitches will remain in place for 12 to 24 months before they are removed.

Both DALK and penetrating keratoplasty have potential long-term issues of irregular astigmatism, cataract formation, steroid responses, and dehiscence of the graft host junction. Thankfully, the global rate of DALK and full thickness corneal transplants for keratoconus has been dropping significantly since the introduction of corneal collagen cross-linking.10

CONCLUSION

Keratoconus is a common condition in Australia. Diagnosing it early and referring patients with the required information can dramatically improve visual outcomes for people. These days, almost all corneas can be cross-linked. Between modern contact lenses and newer surgical procedures, almost all patients should be able to achieve good vision without needing full thickness corneal transplantation.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit mieducation.com/keratoconus-detection-and-management.

References

1. Chan, E., Chong, E.W., Yazar, S., et al., Prevalence of keratoconus based on Scheimpflug imaging: The Raine study. Ophthalmology. 2021 Apr;128(4):515-521.

2. Mukhtar, S., Ambati, B.K., Pediatric keratoconus: A review of the literature. Int Ophthalmol. 2018 Oct;38(5):2257–2266.

3. Medicare Benefits Schedule – Item 42652 Corneal Collagen Cross-linking note TN.8.136 , available at: www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&q=42652&qt=item [accessed April 2024].

4. Belin, M.W., Jang, H.S., Borgstrom, M., Keratoconus: Diagnosis and staging. Cornea. 2022 Jan 1;41(1):1–11. DOI: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002781.

5. Cronin, B., Ghosh, A., Chang, C.Y., Oxygensupplemented transepithelial-accelerated corneal crosslinking with pulsed irradiation for progressive keratoconus: 1 year outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022 Oct 1;48(10):1175–1182. DOI: 10.1097/j. jcrs.0000000000000952.

6. Hafezi, F., Kling, S., Gilardoni, F. et al., Individualized corneal cross-linking with riboflavin and UV-A in ultra-thin corneas: The sub400 protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021; 224:133–142.

7. Cronin, B., Gunn, D., Chang, C., Oxygen-supplemented and topography-guided epi-on corneal crosslinking with pulsed irradiation for progressive keratoconus ASCRS 2023 San Diego Conference, poster presentation.

8. Colin, J., Velou, S. Implantation of Intacs and a refractive intraocular lens to correct keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003 Apr;29(4):832–4. DOI: 10.1016/s08863350(02)01618-8.

9. Sayadi, J.J., Lam, H., Lin, C.C., Myung, D., Management of acute corneal hydrops with intracameral gas injection. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020 Nov 23;20:100994. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100994.

10. Sklar, J.C., Wendel, C., Iovieno, A., et al., Did collagen cross-linking reduce the requirement for corneal transplantation in keratoconus? The Canadian experience. Cornea. 2019 Nov;38(11):1390–1394. DOI: 10.1097/ ICO.0000000000002085.

Dr Brendan Cronin MBBS (Hons) DipOphthSci B.Com LLB FRANZCO is a corneal and anterior segment surgeon and the Director of Education at the Queensland Eye Institute. He performs all types of corneal transplant, sutureless pterygium, micro-incision cataract, LASIK, and MIGS surgery.

Dr Cronin has a special interest in keratoconus, providing customised topography guided collagen crosslinking, advanced micro-transplantation techniques including corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) and excimer laser regularisation procedures.

Take Home Tips

• It is vital to stop any eye rubbing and manage any allergic eye disease immediately in these patients.

• The prevalence of keratoconus in Australia is one in 84 people. Given the high prevalence, if you have a topographer in your clinic, consider performing topography on every patient with a new diagnosis of astigmatism or reduced vision.

• Topography guided cross-linking, topography guided phototherapeutic keratectomy and allogenic intrastromal corneal ring segments (CAIRS) can often help a patient achieve great vision without contact lenses.

• The information in your referral is critical to facilitate treatment. Medicare requires documented progression. Sending serial topography or documenting the change in refractions over time is important information in a keratoconus referral.