miophthalmology

The Three ‘A’s in Clinical Practice: A Guide

WRITER Rushmia Karim

When confronted with aniscoria, anomalous discs, and arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AAION) in clinical practice, the immediate concern is that it’s an ophthalmic emergency. This isn’t always necessarily the case, but as Dr Rushmia Karim writes, it’s important to be methodical in your investigations. Here, she provides a practical guide for clinical practice.

“While it’s always important to consider the red flag causes of anisocoria, more commonly it is related to iris damage, inflammation (posterior synechia) or medications”

ANISOCORIA

Anisocoria describes unequal pupil sizes in an individual. Differential diagnosis can range from the benign physiological anisocoria to emergency causes of Horner’s syndrome from a tumour. The aim of this article is to provide clinicians a clear proforma to aid evaluation and diagnosis.

While a detailed history is ideal, a few questions gauging how long this pupil change has been noted are important. A long-standing difference in the pupil will unlikely need emergency imaging in contrast to a new onset anisocoria. Any history of trauma to the face, eyes or head can induce pupillary changes. Trauma also can include cataract surgery, and phakic lens insertions for refractive correction or retinal surgery. There are a multitude of medications that can cause pupillary changes, including antianxiety/depressants, anti-epileptics, topical glaucoma medications, recreational drug use, and the use of cannabis products. The list of medications is exhaustive, so asking patients specifically about their recent medication changes is also important.1

Examination

It is helpful to have a room that is dark with a low-level back illumination to be able to see the pupil size. Take a few minutes for the pupils to adapt to the dark and check the size of each pupil. Various tools can be used from measuring rulers, pupil charts, and pupilometers. Be careful not to shine light directly onto the pupil when measuring size in the dark.

Brown eyes are particularly challenging to measure and using a low level back of the head illuminator can assist in size recognition without causing asymmetrical pupil constriction during measurement.

Ask the patient to look at a distance-fixation target to reduce pupillary constriction. Measurements in the light should also be performed with time for the pupil to adapt to the light. Carefully watching the reaction of the pupils changing in the light can also aid diagnosis.2

The difference between the pupil size is key. For example, if the difference between the pupils is 2 mm in the dark and 2 mm in the light, the anisocoria is no worse or better in both light and dark. This type of anisocoria is highly likely to then be physiological.3,4 Coupled with a long-standing history of this pupil difference, one can reassure patients that almost 20% of the population have physiological changes in pupil size. This is particularly noted in lighter-coloured eyes due to a higher contrast from a dark pupil and potentially underreported in darker brown eyes. Physiological anisocoria pupil size differences hover around 1–2 mm so with larger pupillary size differences, further investigating is warranted.

If anisocoria is worse in the dark, you must consider Horner’s syndrome. The miosed side is the Horner’s side.5 In long-standing congenital Horner’s (more likely in children), sectoral iris heterochromia is often noted. Clinical features accompanying the pupil changes include ptosis and anhidrosis. In acquired Horner’s there are three levels where a disruption to the sympathetic pathway can occur: central, preganglionic, or postganglionic.1

Testing of Horner’s

Cocaine drops (10%), while not used in the clinical practice, often demonstrate a dilation of the normal pupil and can confirm the clinical diagnosis of Horner’s syndrome. Cocaine inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine, which dilates the pupil. In central Horner’s, the affected miosed pupil will not dilate much as this is the damaged pathway.6 Further, hydroxyamphetamine is equally hard to source but can add information regarding location with dilatation of a central Horner’s but not a postganglionic Horner’s. Apraclonidine, now more commonly used due to ease of obtaining it, will dilate the affected Horner’s miotic pupil.7 This is because the affected miotic pupil has denervation hypersensitivity. Once Horner’s is established, the use of diluted phenylephrine will cause that miosed pupil to dilate in post ganglionic Horner’s. This is due to the denervation hypersensitivity in the postsynaptic terminals. This test would not be done on the same day as the apraclonidine test.6,8

In all suspected acquired Horner’s, it is important to refer to neuro-ophthalmology for appropriate neuroimaging. Depending on the level of Horner’s, different imaging modalities are recommended. Brain/orbit magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally recommended but MRI of the neck/ cervical spinal or brachial plexus should be considered if preganglionic. If the presumed lesion is in the lung, mediastinum, or anterior aspect of the neck, a contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) scan is often sufficient for localisation of the lesion. For third order (postganglionic) Horner’s, those worried about carotid pathology would order MRI brain/orbit plus magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)/ computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the head/neck.9 For carotid neck dissection, an MRI with anatomic cross-sections at the neck is the best image modality.7

Third Nerve Palsy vs Adie’s Pupil

Third nerve palsy is another emergency referral to neuro-ophthalmology or the emergency department. The anisocoria is worse in the light and the parasympathetic innervation is affected. Full third nerve palsy often has associated clinical features of ptosis, double vision, and misalignment with the eyes down and out. This is from a loss of innervation to the levator palpebra superioris, superior rectus, inferior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique. The pupil is often fixed and dilated. In these cases, urgent imaging (MRI/CTA) is warranted to rule out aneurysm, intracranial lesions, and trauma.

Partial third nerve palsies can be more subtle and difficult to diagnose and can mimic

Adie’s pupil without the other clinical signs. This is where diluted pilocarpine (0.125%) causes significant constriction in a pupil with Adie’s tonic pupil but not in a normal pupil. Adie’s tonic pupil is typically seen in young adults and is characterised by a dilated pupil with a sluggish response to light but better constriction with near vision (lightnear dissociation). Over time, Adie’s pupil can become smaller and is known as ‘little old Adie’s’. If possible, attempt deep tendon reflexes – these are usually greatly reduced or absent in Adie’s pupil.1

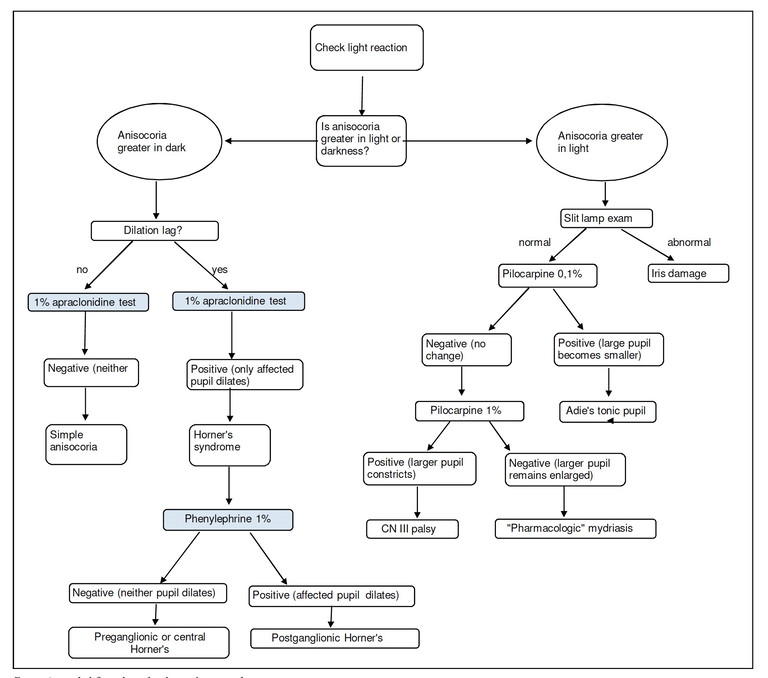

While it’s always important to consider the red flag causes of anisocoria, more commonly it is related to iris damage, inflammation (posterior synechia) or medications (Figure 1).

OPTIC DISC ANOMALIES

Figure 1. Anisocoria pathwayFigure 1. Anisocoria pathway

Anomalous disc is a term to group atypical looking optic nerves. A few common disc appearances that are most likely to be seen in the clinical setting will be discussed.

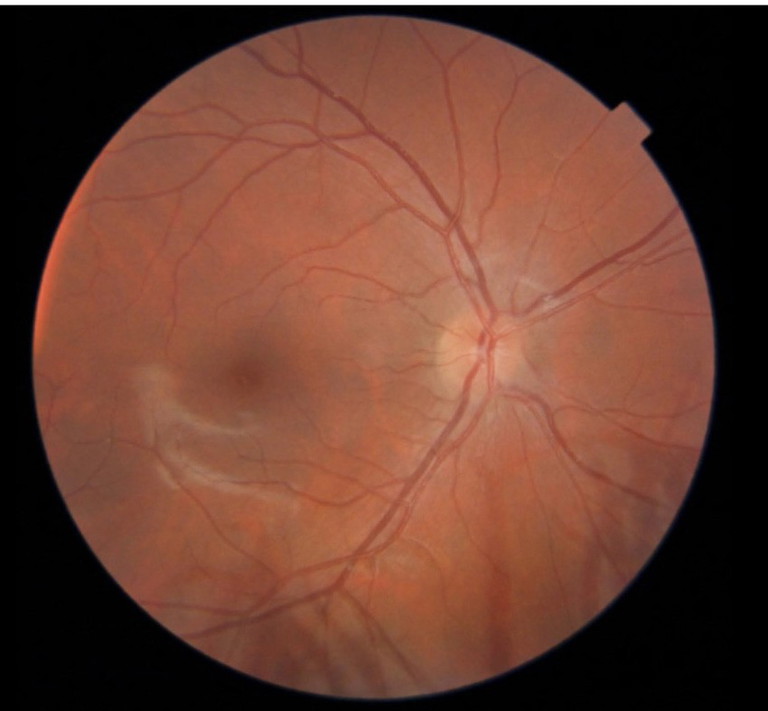

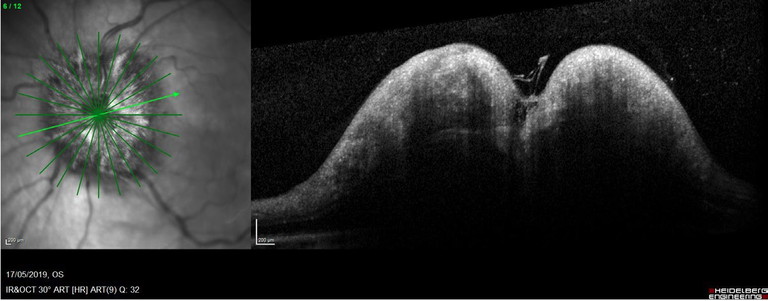

Figure 2. Hyperopic disc with appearance of elevation from small disc size and small cup. Note the prominent nerve fibre layer overlying the disc.

Optic Disc Hypoplasia

Optic nerve hypoplasia is a congenital nonprogressive condition with a characteristic double hump sign. Optic disc hyperplasia in a presenting baby should always be checked for optic disc anomalies. Risk factors in the antenatal setting for optic disc hypoplasia include young maternal age, drug and alcohol syndromes, and diabetes.10 While it is frequently challenging to clearly see the double ring, one can classify risk in other ways. If the optic nerve appears to be further away from the macula – over three-disc diameters during posterior pole examination – this could convey a relatively small optic nerve. Associated eye turns are another red flag and prompt referral is needed for electrodiagnostic testing and a systemic evaluation.

High Refractive Error Nerves

Hyperopic nerves tend to have a smaller nerve diameter by default as patients with hyperopia tend to have smaller eyes. This can give the appearance of a relatively smaller cup and together with a prominent nerve fibre layer, especially in children, give an appearance of blurred disc margins with crowded and raised nerves.10 Patients will typically have spontaneous venous pulsations, good vision with hyperopia, and be asymptomatic. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) will typically show normal retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness in all four quadrants with an absence of the double hump sign of fluid in the subretinal space (Figure 2).

In contrast, myopic nerves tend to be stretched and can give an appearance of higher cup disc ratio from the relatively large optic nerve size. Embryonic and axial lengths stretching throughout can give the appearance of surrounding peripapillary atrophy, which can further mask or confuse the diagnosis of glaucoma.

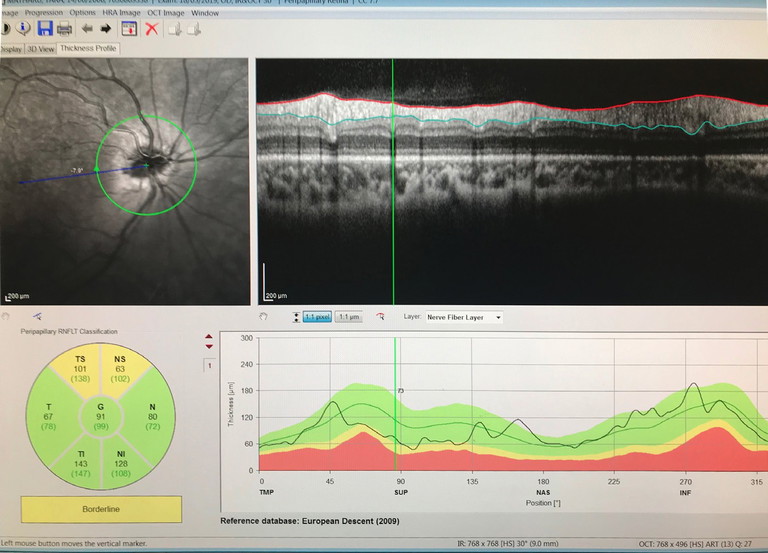

Myopia and astigmatism can further tilt and squash the optic nerve, making surveillance and monitoring of acquired conditions challenging (Figure 3). Tilted disc syndrome, which is a congenital anomaly, is associated with high myopia and can give the appearance of supertemporal elevation of the disc. In rare instances, it can be associated with visual field defects as the optic nerve can enter in an oblique angle and displace the nerve fibres. Very high myopia can result in a posterior staphyloma, which is an outpouching of the globe.11 All high refractive error patients should be monitored regularly to ensure prevention of high-risk ocular sequelae, such as retinal detachment in myopes and narrow angles in high hyperopes.

Figure 3. Tilted myopic nerve with peripapillary atrophy and superior thinning.

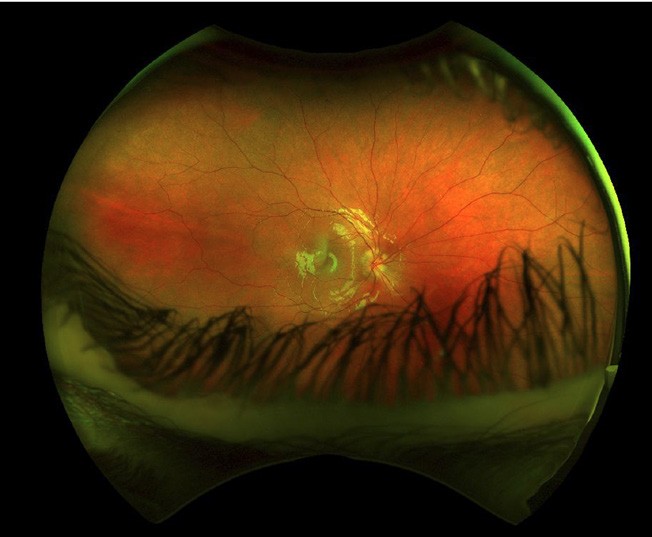

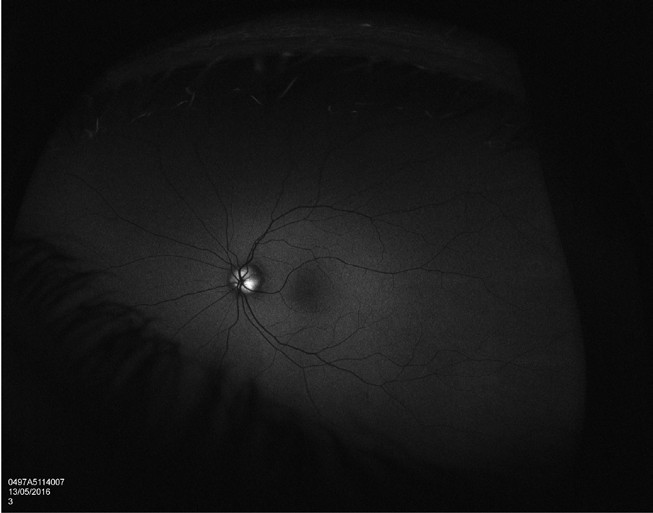

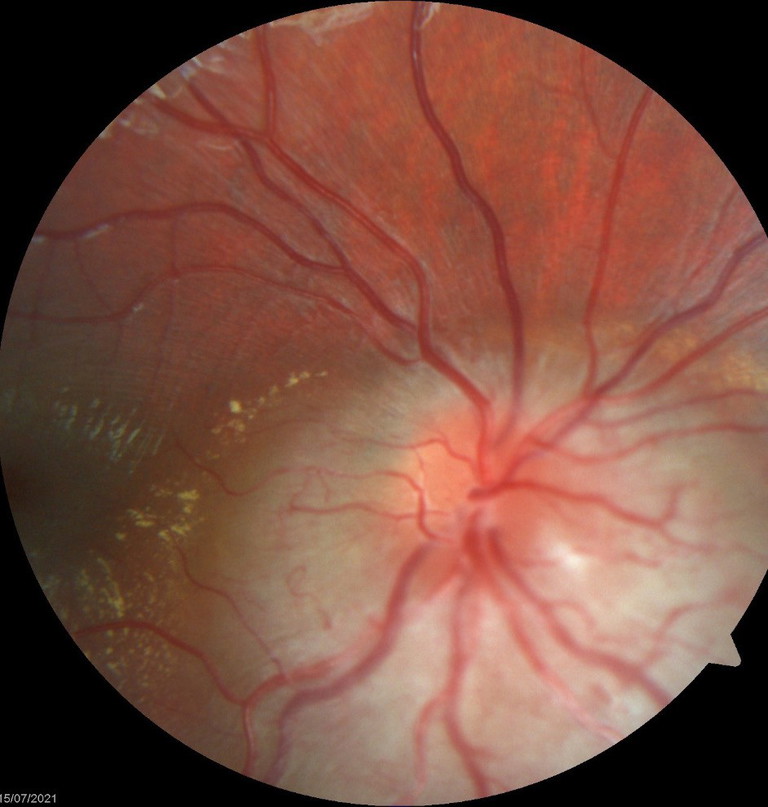

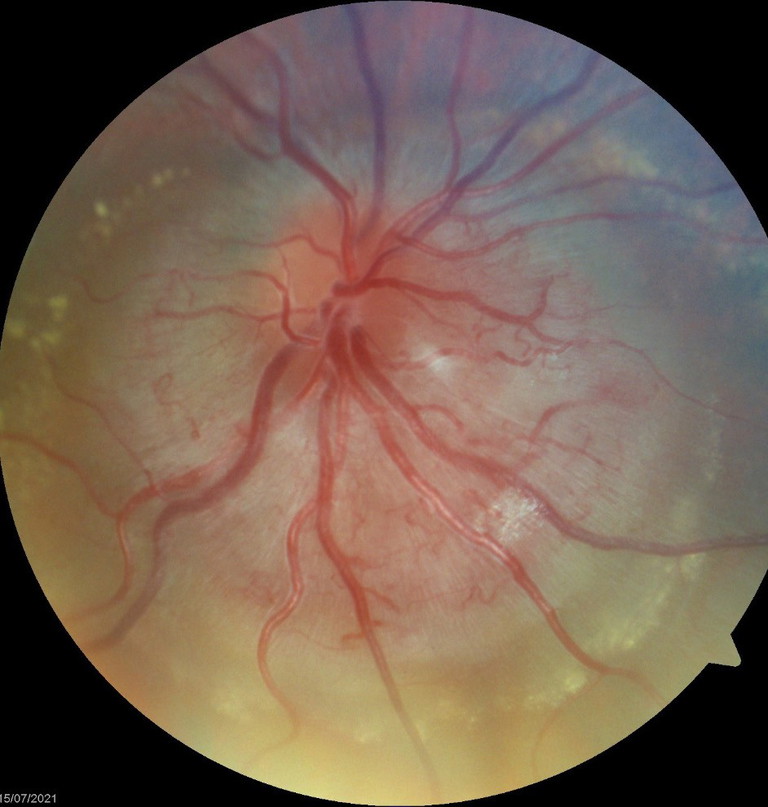

Optic Disc Drusen

With more availability of fundus imaging and extended roles for optometry care, optic disc abnormalities are increasingly being picked up. Optic disc drusen is a common disc anomaly and can present bilaterally or unilaterally. These deposits are found anterior to the lamina cribrosa and are extracellular deposits/axonal debris. While they can mimic papilloedema, and can even cause visual field defects, the presenting history is key. This may present as an incidental finding in an asymptomatic patient. Presence of spontaneous venous pulsations is reassuring. Absence of haemorrhage, and/ or Paton’s lines in a young patient warrants a less urgent evaluation. A fundus photo will show an otherwise healthy fundus and the prominence of the drusen can really be highlighted in fundus autofluorescence. OCT will show a hypo reflective mass surrounding the optic nerve. The presence of drusen can also highlight peripapillary hyperreflective mass structures (PHOMS). B-scan ultrasonography is less utilised due to the ease of Optos or ultra-widefield imaging and OCT, but is quite sensitive in showing the white circumscribed drusen (Figures 4–7).

Disc Swelling

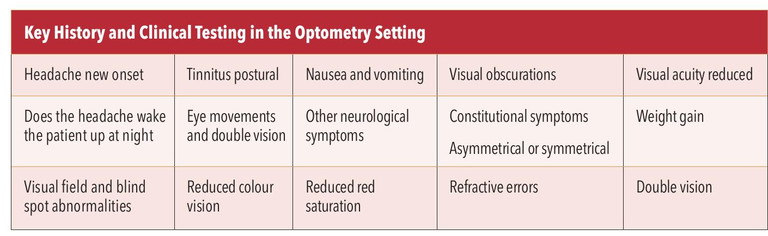

While in many cases, differentiating between real disc swelling and pseudo can be difficult, a thorough case history is key in aiding evaluation (Table 1).

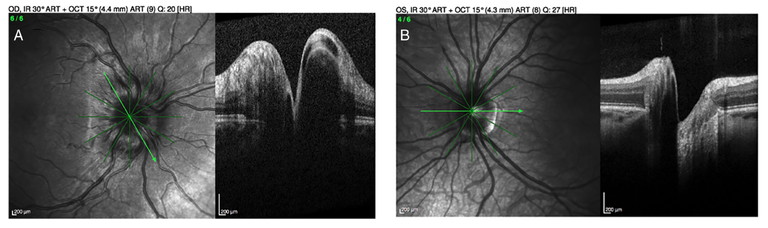

Fundus exam can yield findings of disc haemorrhage, Paton’s lines, loss of spontaneous retinal venous pulsations (SVPs), and obscuration of the vessels.12 Further fundus clues of cotton wool spots, haemorrhage, fluid, or vasculitis can aid in identifying whether a pathological process is happening. OCT has really assisted in differentiating between true disc swelling with increased mean thickening of the RNFL and thinning of the macular cube (ganglion cells). Superior and inferior quadrants thickening was showed to be greater than nasal and temporal quadrants (Figure 8).13 The classic double hump sign, while widely described, can occur in a normal proportion of the population (Figure 9).

Figure 4. Right optic nerve with blurred disc margin and appearance of elevation.

Figure 5. Optos colour image further highlights disc blurring.

Figure 6. Autofluorescence highlights the drusen.

Table 1. Symptoms and signs to watch out for in disc swelling.

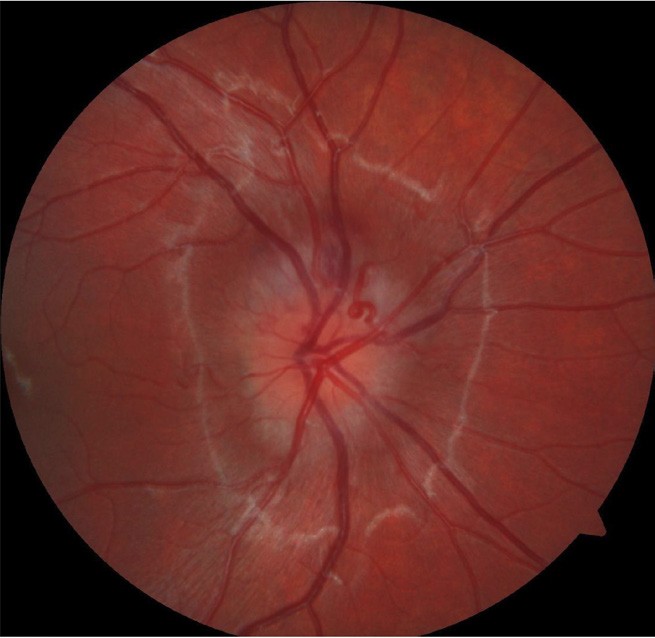

Rare cases of disc anomalies can also scare both optometrist and ophthalmologist alike. Figure 10 is an example of a gross anomalous disc in an asymptomatic patient with 0.1 log mar visual acuity. An interim diagnosis of combined hamartoma of the disc and retinal pigment epithelium was made but continues to be closely monitored.

ARTERITIC ANTERIOR ISCHEMIC OPTIC NEUROPATHY

This ischemic disease, otherwise known as temporal arteritis or giant cell arteritis (GCA), is an eye emergency requiring prompt management. It is a sight-threatening condition and often hard to diagnose. In general, in any acute sight loss, a differential diagnosis of GCA should be considered and excluded based on probability.

GCA is an inflammatory condition that is destructive and leads to ischemia from the obliteration of the vessel walls and hence sight loss. Patients tend to present late when vision is drastically reduced in one eye. There are rarer cases of bilateral disease.14

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published a set of guidelines with five criteria to gauge the risk of a patient having GCA. These signs, symptoms, and diagnostic tests are still used in current practice, albeit slightly modified with the advent of newer image modalities.15

The original 1990 criteria for GCA: 1. Age over 50, 2. New headache (localised), 3. Temporal artery abnormality,

4. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and

5. Abnormal artery biopsy.15

Over the decades, further risk factors have been included for the development of GCA, which include any history of polymyalgia rhematica (PMR), smoking, and history of peripheral vascular disease.16 Over 50% of patients with biopsy positive GCA have an association with PMR.17 Early menopause in women and low body mass can also play a role contributing to vascular ageing. Clinical presentations include scalp tenderness or any form of pain from gentle touch on the skin. New onset headache and jaw or tongue claudication occur in the majority of true cases. It is important to ask patients about fever, weight loss, night sweats, poor appetite, and fatigue. These are constitutional symptoms of malignancy but often present in patients with GCA.

The ocular manifestations of GCA include reduced or loss of vision in one eye. The optic nerve may appear swollen, atrophied, and pale with evidence of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.18,19 There may be associated disc haemorrhage and cotton wool spots. Due to the associated choroidal ischemia and artery occlusion, ordering fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) is reasonable to differentiate disease entities.

Figure 7. Drusen shown clearly on B scan ultrasonography.

Diagnosis

Due to the invasive nature of a temporal artery biopsy and the long duration of treatment involved in GCA, diagnosis is challenging. Presenting symptoms and clinical signs can mimic many other ocular pathologies. Useful laboratory tests include erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C reactive protein (CRP), and plasma viscosity (PV). Generally, an ESR higher than 50 mm/hour or CPR higher than 10 mg/L is considered positive.14 None of these tests are, however, specific and infections or inflammatory conditions can also cause these acute phase reactants (APR) to be elevated. Thrombocytosis of over 400,000 μL has a reasonable predictive score.16

A temporal artery exam can be subjective but, in general, absent pulses and hardening of the wall can be considered abnormal. It is worth trying to palpate the artery in the optometry practice.

A positive temporal artery biopsy is considered the gold standard of diagnosis for GCA. A positive histopathological diagnosis has a very high specificity but obtaining enough tissue is a challenge. Small size biopsy, incorrect biopsy or damaged tissues have caused higher rates of negative results. The disease can also cause skipped lesions – with patchy areas of affected and healthy artery – so biopsy of healthy artery can further yield a negative diagnosis. Hence one can be reassured if the biopsy is positive, but a negative result needs consideration with the overall clinical picture.

Figure 8. OCT imaging highlighting disc swelling (A) compared with pseudo-oedema (B).

Figure 9. Gross optic disc swelling with double hump sign.

Figure 10. Gross disc anomalies presumed to be congenital in nature.

In 2022, the ACR, in conjunction with the European Union League Against Rheumatism, modified the original classification to aid diagnosis in the clinical setting.20 Tests, signs, and symptoms were allocated points and any patient with a total score over six would meet the threshold for treatment. Clinical signs alone could account for a diagnosis in a patient over 50. A presentation of sudden vision loss, jaw claudication, and scalp tenderness could potentially score seven.20

While ocular imaging modalities are not included in the criteria for diagnosis, they aid the clinician. OCT of the optic disc can highlight oedema, pallor, and atrophy. MRI of the orbit can detect optic nerve sheath enhancement, ophthalmic artery vessel wall enhancement, and subclinical inflammation of the asymptomatic eye.21

Simple clinical testing is crucial. In gross visual reduction, the Ishihara colour plates can’t be performed. Visual fields can be attempted if vision is still perceived, resulting in central, altitudinal, or arcuate field loss. Patients often have very poor vision and eliciting an afferent pupillary defect is common and helpful.18

The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommends the use of temporal and axillary artery ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis of new GCA cases, given the low invasiveness, rapid result availability, and comprehensive inflamed vessel visualisation of the imaging modality.

Differential Diagnosis

While it is important to rule out GCA first, non-arteritic ischemic neuropathy (NAION) is more common.22 Other ischemic conditions that need to be considered include carotid artery pathology, intracranial and infraorbital conditions, and hematological malignancies. Infections, particularly varicella and herpes zoster, can cause obliterative vaso-occlusive disease and amyloidosis and systemic lupus are great mimickers of any disease process.23 Migraine and neuralgia conditions are diagnoses of exclusion and often screening bloods, neuro-imaging, and carotid dopplers are warranted.20

Treatment

Prompt treatment of GCA with steroids is key. This can be oral, intravenous methyl prednisolone or any other form of glucocorticoid therapy. If access to hospital facilities and ophthalmic care are difficult, for example in rural locations, it is not unreasonable to start steroid therapy orally and then refer to appropriate services. Steroid therapy should not be delayed to obtain a temporal artery biopsy. In general, a biopsy can still yield positive results five to seven days post initiation of treatment.

“To sum up, with any older patient coming in with unilateral visual field loss and non-specific signs, the mantra isits GCA until proven otherwise”

High doses are started and tapered off with an understanding of the shortand longterm side effects. It is important to add an antacid or proton pump inhibitor to prevent reflux and ulcers from high dose steroid use when starting the prednisolone. Long-term complications should be discussed. These include poor sleep, a change in mental state, a fluctuation in blood sugar levels, infection, changes to bone density, changes to fat distribution, muscle wasting, blood pressure changes, cataracts, and glaucoma.

There is a vast array of longer-term steroid sparing agents that the physician can use including methotrexate, as well as biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD). A landmark study by Bilton et al. showed subcutaneous tocilizumab (TCZ), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signalling by the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, to have good results for both new onset and refractory GCA.16

To sum up, with any older patient coming in with unilateral visual field loss and nonspecific signs, the mantra is “its GCA until proven otherwise”. An urgent ESR /CPR can be ordered with results within hours and prompt referral to emergency ophthalmic and physician care is imperative.

Dr Rushmia Karim BSc MBBS MMed (Ophthsc) MMed (Clinical Epidemiology) Hons Genomics (PG Cert) FRCOphth FRANZCO is an ophthalmologist practising in Sydney and the New South Wales Central Coast. She is a skilled surgeon, performing cataract, refractive lens, and strabismus surgery in both adults and children. She also has a special interest in neuro-ophthalmology. Dr Karim has an extensive research portfolio. She has performed and published systematic reviews including Cochrane reviews, randomised controlled studies, and observational studies. Dr Karim consults at Vision Eye Institute in several locations in New South Wales.

To earn your CPD hours from this article, visit mieducation.com/the-three-as-in-clinical-practice-a-guide.

References available at mieducation.com