mieyecare

Figure 1. Cataract and neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

Cataract Surgery & AMDT

What You Need to Know

WRITER Associate Professor Hemal Mehta

As the population ages, both cataract and neovascular agerelated macular degeneration (nAMD) are becoming more prevalent.1 There are special considerations when managing cataract in patients with nAMD to help optimise visual outcomes and patient satisfaction.2 By understanding pre-operative assessments, surgical timing, intraocular lens (IOL) selection, potential intraoperative risks, and post-operative measures to aid visual function, optometrists can effectively counsel their patients.

Cataract surgery can significantly enhance vision in patients with nAMD (Figure 1), though the extent of improvement varies depending on the severity of AMD and how visually significant the cataract is. In the MARINA and ANCHOR clinical trials of intravitreal ranibizumab for nAMD, cataract surgery was beneficial for eyes with an average improvement of greater than 10 logMAR letters.3 These improvements can be particularly important for maintaining independence in tasks such as reading, driving, recognising faces, and navigating unfamiliar environments.

Cataract surgery may not always reliably improve visual acuity if there is significant foveal atrophy or subfoveal fibrosis, but it will likely improve other critical aspects of visual function such as contrast sensitivity, peripheral vision, and glare, as well as improve quality of life. In a prospective study from Western Australia, the risk of falls decreased by 54% after first eye cataract surgery, compared with the period before first eye surgery.4 The risk of falls decreased by 73% after second eye cataract surgery compared with the period before first eye surgery. Therefore, it is important to consider functional visual benefits beyond visual acuity gains.

ASSESSING MACULAR HEALTH BEFORE CATARACT SURGERY

Before proceeding with cataract surgery, eye care professionals should conduct a thorough evaluation of macular health. This should include macular optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging. In a prospective study, management of 107 (26%) out of 411 patients was modified due to macular spectral-domain OCT findings, with macular conditions either missed (23%) or underestimated (3%) by fundus examination.5 Conditions missed included AMD and epiretinal membrane. Only by actively looking for macular pathology pre-operatively can we provide patients with realistic expectations and optimise cataract surgery outcomes.

TIMING FOR CATARACT SURGERY

The Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB!) registry investigated the timing of cataract surgery in patients with nAMD. Patients who had cataract surgery within six months of initiating anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) therapy for nAMD were more likely to lose vision.6 This suggests that it is important to stabilise nAMD activity before cataract surgery. It is well recognised that cataract surgery increases intraocular inflammation in the short-term. In the previously mentioned ANCHOR and MARINA clinical trials, the average time from the first intravitreal injection for nAMD to cataract surgery was 14 months.3 Therefore, waiting for the nAMD to stabilise with at least six months of intravitreal therapy is recommended where possible.

TIMING INTRAVITREAL THERAPY BEFORE CATARACT SURGERY

Most modern day phacoemulsification cataract surgery is performed without sutures, aiding the speed of visual recovery. It is preferable to allow time for these self-sealing wounds to heal before performing further intravitreal therapy. Therefore, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections for nAMD are usually delivered in the weeks preceding cataract surgery. In the ANCHOR and MARINA clinical trials, intravitreal ranibizumab was delivered in the month prior to cataract surgery with good visual outcomes.3 If intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy is anticipated in the first week after cataract surgery, it would be prudent to place a suture to secure the main wound.

PREDICTING VISUAL ACUITY OUTCOMES

Predicting the extent of visual acuity improvement in patients with concurrent nAMD and cataract is challenging. The FRB! registry identified that the fluorescein angiographic subtype of nAMD (e.g., occult, predominantly classic, retinal angiomatous proliferation) did not impact the visual outcomes of cataract surgery.6 In a retrospective study, foveal ellipsoid zone disruption on macular OCT imaging in patients with nAMD was associated with poorer visual outcomes after cataract surgery.7 Further studies, possibly applying machine learning to large datasets, are required to quantify the impact of imaging biomarkers and cataract grade on visual outcomes to allow for more accurate counselling of patients pre-operatively.

DISCUSSION OF INTRAOCULAR LENS CHOICES

There are special considerations when determining the preferred IOL choice for a patient with concurrent nAMD and cataract. It is helpful to reduce astigmatism where possible with a toric IOL. Modern toric alignment systems built into the operating microscope assist with this.

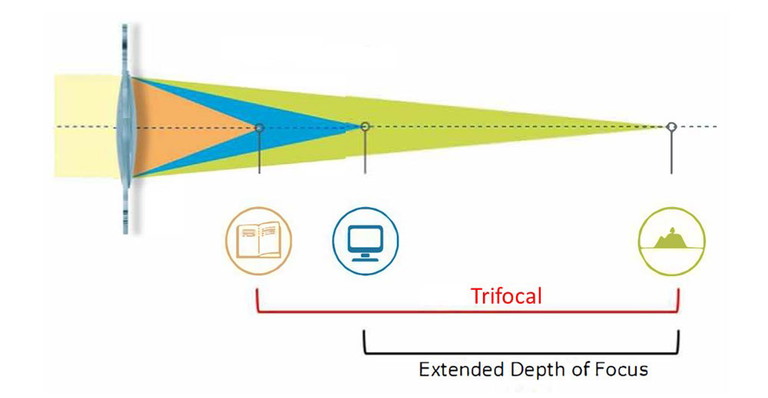

AMD reduces contrast sensitivity. It is advisable to avoid trifocal IOLs, which are associated with reduced contrast sensitivity and increased glare and haloes (Figure 2).

Similarly, small aperture IOLs that aim to provide presbyopia correction should be avoided in patients with AMD (Figure 3). These reduce visualisation of the peripheral fundus and interfere with peripheral macular function, which can be a significant limitation if the central macula is affected by AMD.

There is growing evidence for the use of extended depth of focus (EDOF) IOLs in patients with AMD. They cause less glare and haloes than trifocal intraocular lenses (Figures 4 and 5). A pilot study of 51 eyes with AMD undergoing cataract surgery with the Alcon Vivity intraocular lens implant was conducted in Australia.8 In eyes achieving distance visual acuity of Snellen 6/15–6/24, satisfactory near vision better than N12–N14 was observed. In eyes with significant visual impairment achieving distance VA worse than 6/24, the near vision benefit from the EDOF IOL declines. It should be noted that monofocal IOLs are associated with least glare and haloes and are an option if patients are willing to be more dependent on glasses.

If a sulcus IOL is necessary, because of inadequate capsular support for an IOL in the capsular bag, then the range of IOL options will be reduced.

INCREASED INTRAOPERATIVE RISK OF POSTERIOR CAPSULAR RUPTURE

Eyes receiving intravitreal therapy for nAMD appear to be at increased risk of posterior capsular rupture (PCR) during cataract surgery. PCR is a complication of cataract surgery that can be associated with significantly worse visual outcomes.9 The Royal College of Ophthalmologists of England National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery for cases between 2010 and 2018 reported a mean PCR rate of just less than 1%.10 The hypothesis that previous intravitreal therapy is a predictor of increased risk of PCR during cataract surgery was tested on a large registry of eyes undergoing cataract surgery from 20 UK hospital trusts between 2004 and 2014.11 Data were available on 65,836 cataract operations, of which 1,935 eyes had received previous intravitreal injections (2.9%). Of these injections, 80% were intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy for nAMD. Advanced cataract, patient age, junior cataract surgeon grade, and the number of previous intravitreal injections were associated with increased risk of PCR. A further analysis identified that 10 or more previous intravitreal injections were associated with a 2.6 times greater likelihood of PCR (p=0.003) after adjusting for other significant independent predictors. A number of independent studies from around the globe have supported this observation.12-14

Possible explanations for an increased risk of PCR include inadvertent crystalline lens capsule trauma and zonular trauma (Figure 6), either directly or from local scleral deformation at the time of intravitreal injections.15

Identification of cases at higher risk assists the operative planning and allows patients to be better informed about potential surgical risks.

INTRAOPERATIVELY REDUCING UNNECESSARY LIGHT EXPOSURE

The macula is already unhealthy in AMD and hence may be more vulnerable to light damage.

Prolonged surgery and bright light settings during cataract surgery are potential risk factors for phototoxic macular damage.16 A balance has to be achieved between reducing light exposure and adequate visualisation to perform the surgery safely. The visually significant cataract should reduce the extent of light exposure early in the cataract operation. Once the new IOL is inserted, UV light should be blocked. Therefore, the main time of risk would be when the eye is aphakic and the surgeon can take extra precautions to reduce light exposure during this period of the cataract operation.

Figure 2. Example of the diffractive rings of a trifocal intraocular lens.

Figure 3. Example of a small aperture intraocular lens.

Figure 4. Trifocal intraocular lenses attempt to provide spectacle independence for distance, intermediate, and near tasks. Extended depth of focus (EDOF) intraocular lenses usually target distance and intermediate tasks with the requirement for glasses for reading fine print, particularly in dim lighting conditions. EDOF IOLs may well be better tolerated in patients with AMD.

Figure 5: Principle of an extended depth of focus intraocular lens.

Figure 6: During the intravitreal injection procedure, the needle passes close to the zonules.

Figure 7: Examples of potential low vision aids.

ANTI-VEGF THERAPY FREQUENCY AFTER CATARACT SURGERY

The FRB! registry investigated whether there was a change in the frequency of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections required for nAMD in the 12 months after cataract surgery compared with the 12 months prior.6 Disease activity grading and intravitreal injection numbers were similar in both periods for patients having cataract surgery, whereas both slightly decreased in the control group in the latter 12 months, suggesting that cataract surgery modestly increased the level of nAMD disease activity. Studies without a control group have suggested cataract surgery did not influence nAMD disease activity.17,18

POST-OPERATIVE RISK OF ENDOPHTHALMITIS

Endophthalmitis is a rare but sightthreatening complication after cataract surgery. In an American study of Medicare claims, the risk of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing cataract surgery with a history of intravitreal injections relative to those without were calculated.19 Prior intravitreal injections were associated with increased risk of both acute (hazards ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.001–5.22) and delayed onset endophthalmitis (hazards ratio, 3.65; 95% CI, 1.65–8.05). The authors recommended increased post-operative vigilance in patients with a history of intravitreal injections undergoing cataract surgery.

POST-OPERATIVE VISUAL AIDS

After cataract surgery, the benefit of additional lighting or magnification in patients with AMD should be re-considered (Figure 7). Patients may find low vision aids more beneficial once they have clear media after cataract surgery. Local patient support groups can offer routes to access these. Glasses are usually updated one month after second eye cataract surgery. A Cochrane Review of low vision aids identified no good evidence to support the use of filters or prism spectacles in patients with low vision.20

Associate Prof Hemal Mehta MBBS MD (Cantab) FRCOphth FRANZCO is an experienced macular disease specialist and cataract surgeon consulting in Sydney and the NSW Central Coast.

He is on the Therapeutics Committee of RANZCO and the editorial board of the journal Eye. The clinical research during his previous fellowships at Sydney Eye Hospital and Moorfields Eye Hospital contributed to his higher research degree from Cambridge University. He is co-Director of Clinical Trials Research at Strathfield Retina Clinic and has served as principal or sub-investigator in over 50 clinical trials. Assoc Prof Mehta has contributed to peer-reviewed publications and national guidelines on management of cataract in patients with macular disease.

References

1. Steinmetz JD, Bourne RR, Briant PS, et al; GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9(2):e144–e160. doi: 10.1016/S2214109X(20)30489-7. 2. Mehta H. Management of cataract in patients with agerelated macular degeneration. J Clin Med. 2021;10(12): 2538. doi: 10.3390/jcm10122538.

3. Rosenfeld PJ, Shapiro H, Ehrlich JS, Wong P, MARINA and ANCHOR Study Groups. Cataract surgery in ranibizumab treated patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration from the phase 3 ANCHOR and MARINA trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):793-798. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.04.025. 4. Feng YR, Meuleners LB, Agramunt S, et al. The impact of first and second eye cataract surgeries on falls: A prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13: 14571464. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S164419. 5. Weill Y, Hanhart J, Abulafia A, et al. Patient management modifications in cataract surgery candidates following incorporation of routine preoperative macular optical coherence tomography. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020; 47(1):78-82. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000389. 6. Daien V, Nguyen V, Barthelmes D, et al. Fight Retinal Blindness! Study Group. Outcomes and predictive factors after cataract surgery in patients with neovascular agerelated macular degeneration. The Fight Retinal Blindness! Project. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;190:50-57. doi: 10.1016/j. ajo.2018.03.012. 7. Chen AX, Haueisen A, Rasendran C, et al. Visual outcomes following cataract surgery in age-related macular degeneration patients. Can J Ophthalmol. 2021;56(6):348354. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2021.01.018. 8. Thananjeyan AL, Siu A, Jennings A, Bala C. Extended depth-of-focus intraocular lens implantation in patients with age-related macular degeneration: A pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:451-458. doi: 10.2147/OPTH. S442931. 9. Sparrow JM, Taylor H, Johnston RL, et al, UK EPR user group. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multi-centre audit of 55,567 operations: Risk indicators for monocular visual acuity outcomes. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(6):821-826. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.51. 10. Buchan JC, Donachie PHJ, Sparrow JM, et al.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: Report 7, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery in the UK: Current practice and patient selection. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(10):1866-1874. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0761-z. 11. Lee AY, Day AC, Egan C, et al. Previous intravitreal therapy is associated with increased risk of posterior capsule rupture during cataract surgery.

Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1252-1256. doi: 10.1016/j. ophtha.2016.02.014. 12. Hahn P, Jiramongkolchai K, Kim T, et al. Rate of intraoperative complications during cataract surgery following intravitreal injections. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(8): 1101–1109. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.109. 13. Shalchi Z, Okada M, Whiting, C.; Hamilton, R. Risk of posterior capsule rupture during cataract surgery in eyes with previous intravitreal injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;177:77-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.02.006. 14. Nagar AM, Luis J, Patra S, et al. The risk of posterior capsule rupture during phacoemulsification cataract surgery in eyes with previous intravitreal anti vascular endothelial growth factor injections. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020; 46(2):204-208. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.09.004. 15. Mehta H, Tufail A, Gillies MC, et al. Real-world outcomes in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;65:127146. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.12.002. 16. Wolffe M. How safe is the light during ophthalmic diagnosis and surgery. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(2);186-188. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.247. 17. Grixti A, Papavasileiou E, Prasad S, et al.

Phacoemulsification surgery in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. ISRN Ophthalmol. 2014;2014: 417603. doi: 10.1155/2014/417603. 18. Kessel L, Koefoed Theil P, Lykke Sorensen T, Munch IC. Cataract surgery in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94(8):755760. doi: 10.1111/aos.13120. 19. Hahn P, Yashkin AP, Sloan FA. Effect of prior anti-VEGF injections on the risk of retained lens fragments and endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in the elderly. Ophthalmology 2016;123(2):309-315. doi: 10.1016/j. ophtha.2015.06.040. 20. Virgili G, Acosta R, Evans JR, et al. Reading aids for adults with low vision. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4(4):CD003303. doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD003303.pub4.