mieducation

Which Comes First: Dry Eye Disease or Depression?

October is Mental Health Month in Australia with 10 October recognised as World Mental Health Day globally. In this article, Neil Retallic sparks a discussion around the relationship between dry eye disease and depression, highlighting various initiatives to raise awareness of mental health conditions.

WRITER Neil Retallic

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Understand the association between dry eye disease and depression,

2. Understand best practice approaches to investigate and manage patients with dry eye disease and depression, and

3. Understand how dry eye and depression may typically present to optometric practice.

Figure 1. Researchers highlighting the association between mental health and dry eye from the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society lifestyle reports at the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA) 2023 Clinical Conference in Manchester. Image courtesy BCLA.

Philosophy means ‘love of wisdom’ and although some philosophical debate topics such as ‘Can vegetables feel pain?’ may seem peculiar, other more carefully selected choices can result in moments of deep critical thinking.

For eye and health care providers, thoughtprovoking discussions on seemingly unanswerable questions may lead to finding solutions to health service provision issues, which could ultimately enhance patient care and strengthen multidisciplinary working relationships.1

There are a plethora of publications linking mental health conditions like depression to ocular pathology such as dry eye disease (DED). It is, therefore, no surprise that this association is of interest and receiving attention (Figure 1).

Numerous studies have confirmed that depression is more prevalent in those with DED than in the general population and have found links to severity levels.2-4 One study found anxiety or depression was reported by nearly half (47%) of adults with DED compared to around a third (32%) in those without the condition.2

These staggering statistics provoke the question between ophthalmology and psychiatry: does one condition trigger the manifestation of the other?

COMMON RISK FACTORS

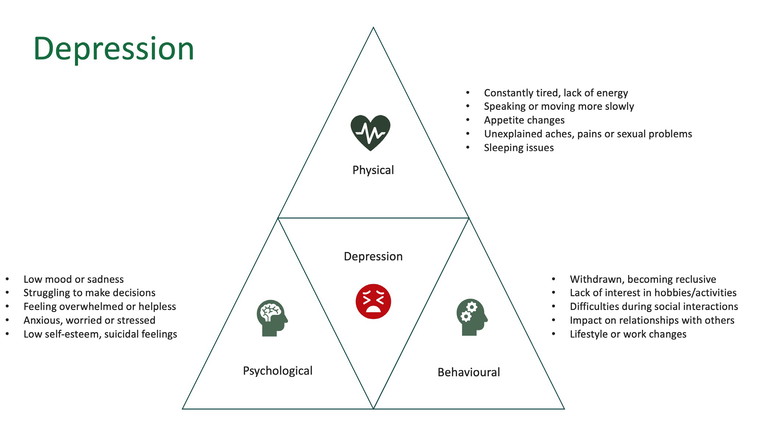

Depression and DED are complex conditions that share several similarities, including some common risk factors, with negative impacts on quality of life and overall health. Individuals with depressive signs and symptoms (Figure 2) may initially present during consultations in community eye care settings. While signs of mental health issues may not instantly jump out to the eye care practitioner during routine investigations such as dry eye assessments, with a proactive holistic approach, we are well placed to identify and support those suffering from mental health conditions and any associated ocular pathology.

Our careful history taking can help identify key risk factors and issues that have been associated with both DED and depression.

Gender, Hormonal Changes, and Age

Depression is twice more common among women than men, with the odds increasing with age.5 Interestingly, the triggers and appearance of depression also appear to be different. Women more commonly present with internalising symptoms, such as sadness, anxiety and loneliness, triggered by interpersonal relationships. Men most often present with externalising related symptoms, such as aggression and hyperactivity, triggered by career and goal orientated factors.6 Hormone related reasons also have been proposed, which may account for why depression is more common during pregnancy and menopause.6

Figure 2. Potential signs and symptoms of depression.

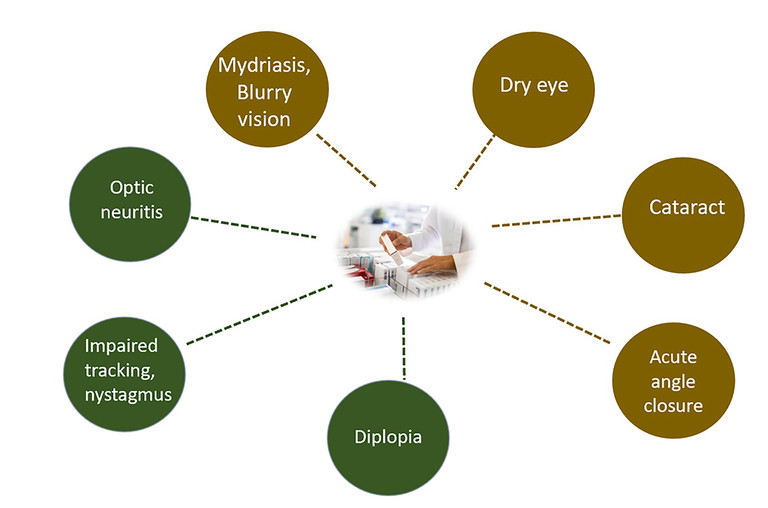

Figure 3. Potential ocular side effects from depression medications. Symptoms marked in brown are more common side effects, while green are rarer side effects.

Similarly, with DED, higher prevalence levels are reported in women when compared to men. This is particularly true of women in menopausal and postmenopausal age groups with comorbidities. It is believed that changes in the balance of sex hormones – oestrogens and androgens – may impact the secretion of meibum, leading to DED.7

There is evidence that some of the natural age associated changes that occur may increase a person’s risk of experiencing depression. Similarly, the ageing process is known to change numerous aspects of the ocular surface microenvironment, decreasing tear production and tear film stability, and subsequently increasing the chance of DED.8

Digital Devices

Excessive use of digital devices, including smartphones, has been linked to depression and dry eye.

Those spending more than six hours a day viewing screens are more likely to have moderate to severe depression than those who spend less time on screens. The theory proposed is that social isolation and lack of real human connections creates a vicious cycle that worsens symptoms of depression.9

Dry eye has also been linked to the use of digital devices. Reducing screen exposure time and advice on blink rate and completeness may be beneficial.10

Lifestyle

Vitamin-A deficiency is a risk factor for dry eye and nutrient deficiencies, such as folate/vitamin B9, B12, and vitamin D, are linked to higher risks of depression.11,12 Omega 3 fatty acids are associated with both conditions.11,13

Making changes to address poor diet and bad habits, such as excessive alcohol consumption or smoking, are considerations as part of management plans for patients with depression. Similarly, alcohol has been linked to tear film disturbances and dry eye disease symptoms, tobacco use to tear instability, and cocaine to decreased corneal sensitivity.4

Systemic Disease and Treatments

Connective tissue disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, and sleep disorders are examples of conditions that are linked to both DED and depression.

Some treatments, for example undertaking radiation therapy, are also common to both conditions.4

THE LINK BETWEEN ANTIDEPRESSANTS AND DRY EYE

Antidepressants are powerful drugs that work by increasing the levels of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and noradrenaline in the brain, to address chemical imbalances and improve mood.

They have been shown to increase dryness in the body, including the eye, by blocking signals between nerve cells thought to lead to insufficient tear production and DED.14

A staggering one in seven Australian adults (over three million people) take antidepressants for depression and anxiety every day,15 with sertraline – a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) – now one of the country’s top 10 most prescribed drugs.16 In New Zealand, there are over two million annual initial dispensings of antidepressants.17

Potential ocular side effects from medication taken for depression (Figure 3) include: pupillary dilation, ocular redness, tear film changes, dry eye symptoms, blurry vision, reduced accommodation, increased intraocular pressure, glaucoma risk (closed angle glaucoma symptoms), and vascular changes.18 A review of antidepressant package inserts found that some (16%) document dry eye as an infrequent risk.18

CAN DEPRESSION AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS CAUSE DRY EYE?

The link between antidepressant medications and DED adds fuel to the debate about whether depression can lead to dry eye.

One further hypothesis for why depression can lead to symptomatic dry eye is the result of a lower threshold for perceived physical pain, resulting in an increased likelihood of symptoms becoming manifest. Brain-derived neurotrophic factors may play a part, as without the ‘Miracle-Gro’ to keep the brain health functioning and to stimulate new cell growth, both depression and dry eye could result.14

A small-scale study found raised levels of proinflammatory markers – cytokines including IL-interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-7 (IL-7) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) – were found in the tear film of individuals taking antidepressants when compared to healthy controls, with the suggestion that this may lead to the worsening of DED.

The larger scale DREAM study concluded that the inflammatory markers did not differ by depression status and found most pro-inflammatory tear marker levels were similar, except for IL-6, which were higher in antidepressant medication users.3

But while some studies have found correlations, other studies have concluded this association to be independent of antidepressant medication use.19 It is worth noting that studies exploring these aspects are not without limitations, given the difficulties in isolating specific parameters. Further research will help us form more comprehensive conclusions.19

As an additional complication, although anti-depressant medications may exacerbate DED, and have been identified as a risk factor for DED, effective management of depression may help to alleviate DED symptoms.14 It is also important to remember that symptoms can be masked by medication.20

This link between depression, antidepressant medications, and DED highlights the need for an interdisciplinary approach to holistic patient care.14,21

COULD DRY EYE DISEASE LEAD TO DEPRESSION?

DED can reduce visual performance and impair quality of life. A potential explanation linking DED to depression is the burden from the chronic ocular pain and discomfort that affects a person’s ability to function effectively, triggering depression and/or anxiety traits.21

Studies have associated dry eye with poorer self-perceived health status and greater psychological issues. Frustration with DED can also lead to less social interactions and feelings of unfulfilled achievements, potentially contributing further to mental health issues.

Comorbidities are common among those with dry eye symptoms, with twice as many suffering from arthritis, hearing loss, and irritable bowel disease as those who did not have DED. The combined impacts may impair functionality during everyday activities and predispose DED patients to mental health conditions.3

QUESTIONNAIRES: HEALTH-RELATED PATIENT REPORTED OUTCOME MEASURES

To assess the severity of DED and any impact on quality of life, researchers have established various questionnaires, that may be introduced in practice, including:

• Ocular Surface Disease Impact (OSDI)

• Ocular Comfort Index (OCI)

• Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5)

• EuroQol 5 Dimensions Levels (EQ-5D-5L)

• Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL)

Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) triaging questions are also useful to complement history taking.22

The association between dry eye symptoms and depression appears better correlated than to DED clinical signs,4 and the severity of DED symptoms tends to be higher in patients suffering from depression, with some researchers suggesting that serotonin in the tears has a role by being dysregulated by the disorders.23 Exploring any visual changes is also important as visual blurring has been associated with symptoms of depression, most likely due to the optical aberrations induced by dry eye predisposing to depressive tendencies.

Two common questions used in primary care to screen for depression prior to further assessment are 1) have you felt down or depressed or hopeless? and 2) have you been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things? The time frame is usually over the past month with yes/no responses, or two weeks as part of the Patient Health Questionnaire. The latter has four scale options (ranging from not at all to nearly every day) and there are various versions of the questionnaire available (total number of questions differs) with the longer versions providing a selfreported measure of severity.

CLINICAL INVESTIGATION OF DRY EYE AND MENTAL HEALTH

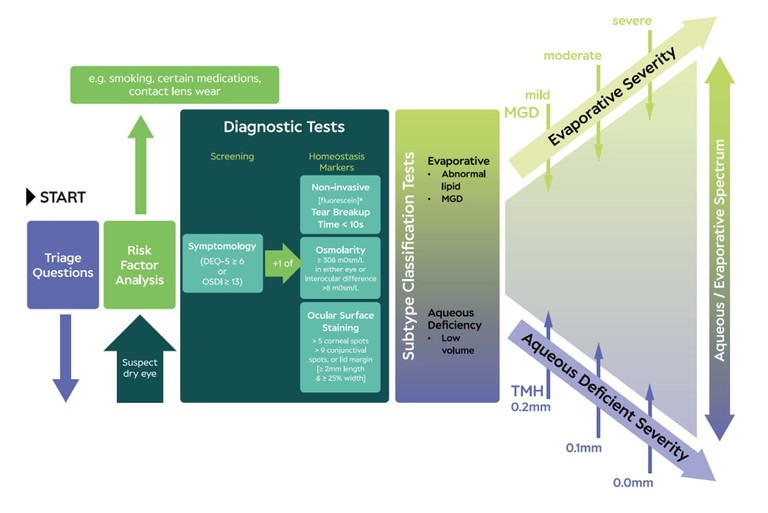

To comprehensively investigate dry eye disease, it is wise to follow the guidance in the TFOS DEWS II reports (Figure 4), taking a least to most invasive test approach.22

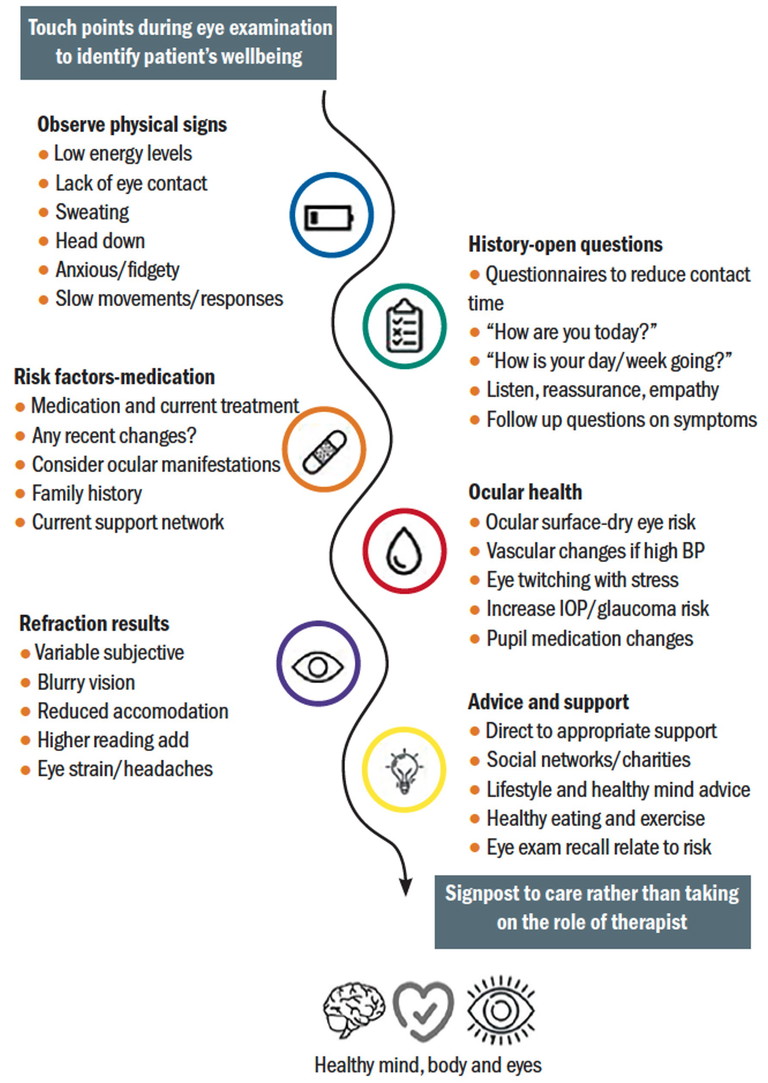

There are various touch points during routine consultations (Figure 5) where signs of declining mental health can be identified.24 Key to success is building a good rapport with the patient, observing behaviours and responses, active listening, and asking open questions with relevant follow-up questions.

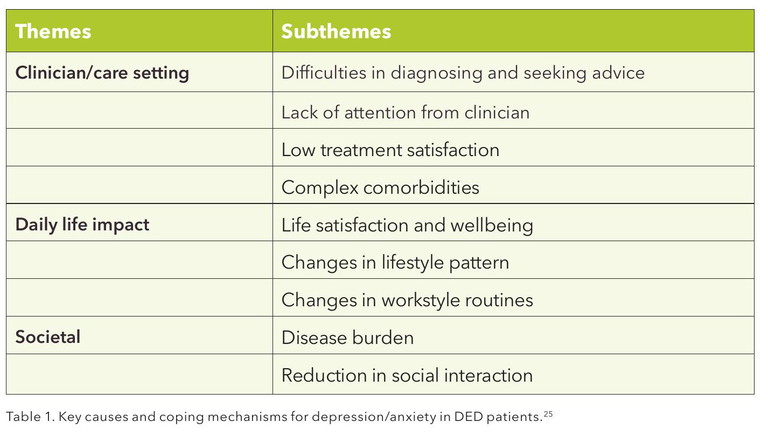

EXPERIENCES WITH DRY EYE AND DEPRESSION

A study analysing patient interviews categorised the causes of anxiety and depression in those with DED into three main themes: clinician related, from daily life, and society induced, with nine further subthemes (Table 1).25 This shows the unintended consequences clinicians can have and the importance of focussing on clinical decisionmaking and communication approaches.

Common examples included mild cases that were undiagnosed in time for early intervention, which led to an exacerbation of the condition and unrealistic expectations from treatment outcomes due to perceived contradictory clinical advice. The latter is not surprising given clinical signs may show improvements before symptoms, leading patients to often feel like the treatment is ineffective or taking too long to work, despite the clinician’s reassurance in the treatment plan. As a result, some self-modify their treatment plan by ceasing, reducing or overmedicating.25

Figure 4. TFOS DEWS II DED diagnosis criteria.22

“DED and depression are closely linked and influence one another in ways that radically impact patients’ lives, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear.”

Figure 5. Touch points for considerations of wellbeing aspects.24

MANAGING PATIENTS WITH DRY EYE AND DEPRESSION

For DED, the management plan should include the usual considerations. Typically start with education; recommending ocular lubricants; treating any co-existing pathology; lid hygiene/warm compresses; lifestyle, environmental and dietary advice; addressing modifiable risk factors; offering in office therapies, and – for more advanced disease therapeutic options – inflammatory control (topical corticosteroids), punctual plugs, or other surgical approaches.26

For those at risk or suffering from depression, an eye care practitioner is well placed to listen, respond in an empthatic manner, provide general advice, and signpost to appropriate care.24 Sometimes active listening and reassurance is enough. Mental health organisations advocate for conversations that focus on empowering the individual to set their own achievable goals to address risk factor/ bad habits, establish new routines, and where appropriate, seek professional help rather than trying to diagnosis the exact conditon.

Treatment for depression usually consists of self-help, healthy living lifestyle changes, medications and/or psychological therapies. Supplements that have been explored for patients with depression include methylfolate, omega 3 fatty acid, and Hypericum perforatum.20

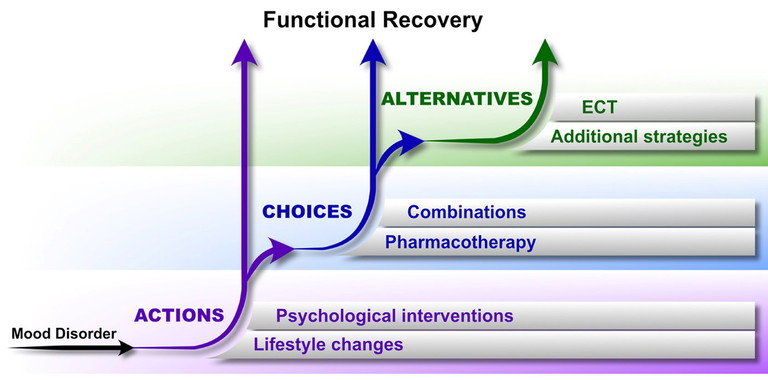

Figure 6. Foundations of treatment in the 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders.21

Recent guidelines tend to favour psychological therapies as first line options for mild depression over medication and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines (Figure 6) recommend starting with non-negotiable actions then progressing to choices, and finally providing alternatives, depending on the patient’s needs.20

Self-help therapies may consist of activities designed to be completed independently at times that best suit the individual and could involve ways to introduce subtle lifestyle changes. There are also guided self-help options, for example working through a workbook or computer course with the support of a therapist.

Examples of psychological therapies include cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which aims to change the way the person thinks and behaves, another is interpersonal therapy (IPT), which focusses on relationships with others, and counselling, which helps with finding new ways to deal with the problems experienced in life.

While antidepressants can help treat the symptoms of depression, they do not always address the cause. A study reviewing prescribing trends in Australia between 2013–19 found the most prescribed antidepressants were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (52%), tricyclic antidepressants (25%), and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (13%), with other medications making up the remaining 10%.27 The usual course is taken for six to 12 months, or up to two years in people at risk of relapse,15 although around half of people experience withdrawal symptoms28 and may end up on medication for the long term, with the average duration being four years.15 The benefits these drugs provide are likely to outweigh any risk of ocular manifestations such as dry eye.

There are numerous free mental health services that are worthy of promoting to ensure individuals can get the right support. In Australia some examples are: Lifeline, Beyond Blue, and various confidential services provided by the Australian Government such as Head to Health.

For those in New Zealand, options include: The Depression Helpline, Samaritians, Lifeline, and 1737 Need to Talk?

CONCLUSION

Around one in every four individuals with eye disease has depression, with the highest prevalence levels found in those with DED.29

DED and depression are closely linked and influence one another in ways that radically impact patients’ lives, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear. It makes sense then, that when appropriate, dry eye sufferers should be considered for psychological support alongside traditional DED management.

While we may not have the perfect answer to our question, further research will enhance our understanding and hopefully enable us to conclude whether this complex intrinsic relationship is more of a psychiatric or ophthalmic complaint, or simply bidirectional, with both having the potential to cause and effect the other.

For now, the direction for clinicians is clear: by taking a holistic patient-centred care approach, tailoring our eye care services, and developing closer multidisciplinary working relationships, we can provide the best patient outcomes.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit: mieducation.com/which-comes-first-dry-eye-disease-or-depression.

References available at mieducation.com.

Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience working in practice, education, industry, and head office roles. He currently works for Specsavers and the College of Optometrists in the United Kingdom and is a Past President of the British Contact Lens Association. He is completing a PhD on mental welfare among the profession with the University of Bradford.

World Mental Health Awareness

World Mental Health Day (10 October 2024) is a campaign endorsed by the World Health Organization, with the overall objective of raising awareness of mental health issues around the world and mobilising efforts in support of mental health. The 2024 theme, as set by the World Federation for Mental Health, is ‘It is Time to Prioritize Mental Health in the Workplace’. For further information visit: wmhdofficial.com.

National Mental Health Week (7–14 October 2024) in Australia is scheduled around World Mental Health Day, with states organising activities under various mental health themes. The Suicide Call Back Service has a state-by-state summary, visit: suicidecallbackservice.org.au/mental-health/whats-happening-during-mental-health-week.

In New Zealand, Mental Health Awareness Week was held in September.