mieducation

Contact Lens Wear and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

In clinical practice, we can expect to see children and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. For these individuals, apart from providing the required basic eye care, should we consider contact lenses as a visual correction option or even a myopia management intervention? The answer may not be that clear cut given the multifactorial nature and varying severity of these conditions. Being adaptable, and tailoring our decisions relative to the individual’s need, will aid in determining contact lens suitability. Neil Retallic and Dr Ketan Parmar present tips and tricks for use in practice.

WRITERS Neil Retallic and Dr Ketan Parmar

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Be aware of the range of neurodevelopmental disorders that may present in clinic,

2. Realise how contact lenses can improve quality of life for some people with neurodevelopmental disorders,

3. Understand the need to balance currently available guidance, clinical judgement, and patient needs, and

4. Be equipped with tips for a successful eye examination and contact lens fit.

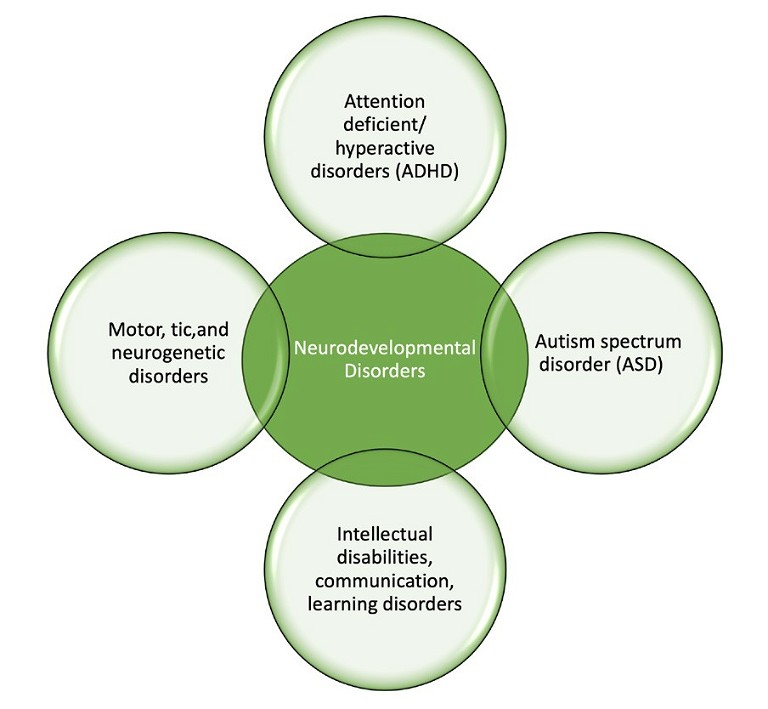

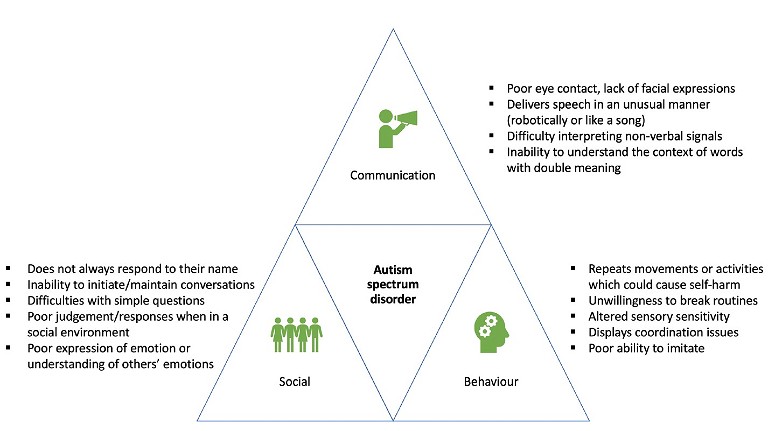

The World Health Organization defines neurodevelopment disorders as a group of conditions that lead to impairments, causing difficulties in social, cognitive, and emotional functioning. Common examples of such conditions (Figure 1) include autism spectrum disorder (ASD/ autism), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disorders that impact intellectual, communication, learning or motor abilities.1 However, there are challenges in grouping complex diverse disorders together: boundaries between conditions are often unclear, and comorbidity is common.2 Studies across the globe have reported variances in the prevalence of neurodevelopment disorders among children, ranging from 4.7% to 88.5%.3 Changes to reflect more politically acceptable nomenclature have resulted in various terms and language being used to describe these disorders and the symptoms.4

The term ‘intellectual disability’ (known as ‘learning disability’ in the United Kingdom) is used to umbrella those with a lifelong developmental disorder where major difficulty or delay in acquiring skills occur before adulthood, which then impairs the ability to learn and function to the expected level. The UK’s National Institute of Clinical Excellence has three criteria elements: a low intelligence quotient (IQ) (under 70), significant impairment of social or adaptive functioning, and onset during childhood.5

About half a million Australians6 and approximately 50,000 New Zealanders7 live with an intellectual disability. Almost 60% have severe communication limitations, which distinguishes intellectual disability from other major disability groups for which severe limitations are more concentrated in self-care and mobility.8 Examples are broad ranging and include genetic conditions such as Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome, or conditions linked to infections, brain injury, exposure to toxic substances, birth complications or interferences in brain development, including cerebral palsy.

In Australia, learning disabilities is a subcategory to cover those with a reduction in certain academic skills (literacy and numeracy), which do not necessarily affect the person’s IQ, general intelligence, or independence. Examples include dyslexia, dyscalculia, ADHD, and ASD.

CONTACT LENS WEAR

The broad spectrum of neurodevelopmental conditions clearly highlights that a ‘one size fits all’ approach with eye care provision will not generate the best patient outcomes.

Surprisingly, despite the many psychological, practical, and visual benefits of contact lenses,9 little has been published on contact lens fitting for these particular populations. Guidance is available from professional bodies on communication aspects and reasonable adjustments to make during the eye examination.

One of the initial barriers may in fact be down to us, as eye care providers, failing to initiate these conversations.10 With the right motivation, fitting is possible following a comprehensive risk/benefits analysis including reviewing handling aspects, likelihood of good compliance, eye/general health aspects, and the patient’s ability to communicate any sub-optimal performance or symptoms/signs of infection. The support network around the individual can also be used to overcome any challenges and monitor progress.

Figure 1. Examples of common neurodevelopmental disorders.

Figure 2. Situations in which contact lens wear would be contraindicated.

Additionally, it is our duty to establish capacity, obtain consent, involve others in decisions regarding the patient’s care (where appropriate), communicate in a manner easily understood by all parties, maintain appropriate records, and ensure safety.

Contact lenses must not be fitted if patient safety is likely to be compromised (Figure 2). Where a patient’s capacity to give consent is impaired or limited, obtaining the consent of the person(s) with legal authority to act on behalf of the patient should take place. Working within our scope of practice is essential. More details on these aspects can be found in the Optometry Board of Australia Code of Conduct for Optometrists.11

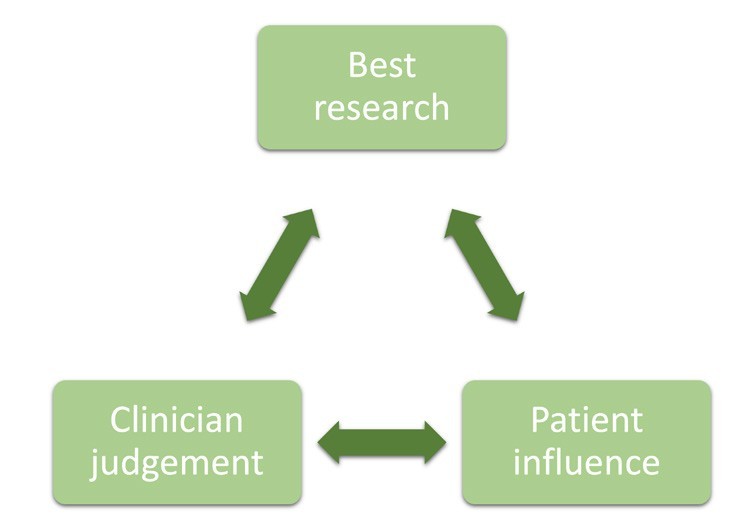

The remainder of this article explores the role contact lenses may play in addressing the eye care requirements of neurodiverse populations using case examples. Safe contact lens wear is the goal, and suitability should be determined on a case-by-case basis, with the patient fully involved in the decision-making process. Contact lens prescribing, fitting, and management should follow an evidence-based approach (Figure 3), which considers best practice guidance available, applying clinical judgement and incorporating any preferences of the patient/carer.12

CASE 1: BEN, A PATIENT WITH ADHD

ADHD is a complex neuro-developmental disorder affecting the individual’s ability to exert age-appropriate self-control, usually through patterns of impulsive hyperactive behaviour and periods of inattentive activity. Emotional regulation challenges may also occur, however with the right support and treatment, individuals can learn to manage these challenges.

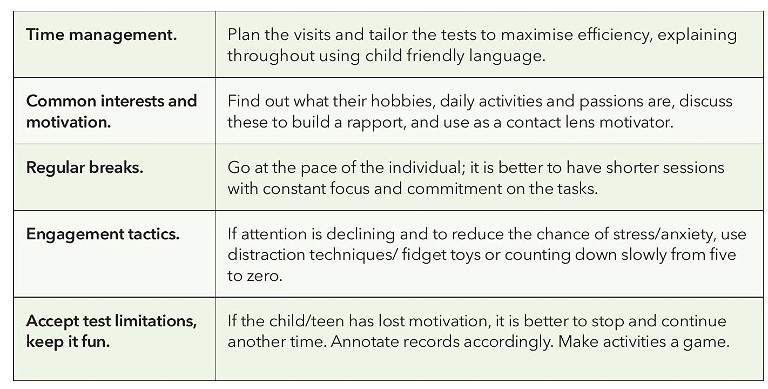

Table 1. Tips to enhance the contact lens fitting process for patients with ADHD.

ADHD affects around one in 20 children in Australia and New Zealand.13 There is a higher likelihood of refractive error, binocular vision (e.g., strabismus, amblyopia, and symptomatic convergence insufficiency), visual field defects, and colour vision deficiency in children with ADHD compared with those without.14-17 This highlights the importance of individuals with ADHD undergoing a thorough eye examination to rule out, and where appropriate treat, any underlying vision issues that are likely to impact vision-related quality of life.

Ben,* who is 15 years old, was diagnosed with ADHD three years ago. He wears glasses full time (R&L -2.00D 6/5 N4), although regularly breaks them. His mother reports he is “doing well at school, when he stays focussed”. On examination, there are no clinical/eye health contraindications to contact lens wear identified. He is compliant with taking his medication (5mg methylphenidate twice per day). He seems engaged during the eye test, and capable of understanding information and making decisions, although easily becoming distracted. Ben loves sport.

His mother asks if contact lenses would be a good option.

Would you fit Ben with contact lenses?

We know children generally do well with contact lenses and can demonstrate compliance.18 If Ben is motivated and consents, his impulsive and “make it happen” tendencies can be used as a strength. With the right approach, his energy can be focussed on this new, exciting opportunity to wear contact lenses. Ben seems to understand information and is willing to be involved in decisions. His visual acuity is good, and he appears to have family support. The usual contact lens options (soft and rigid materials) and the fitting process are applicable and should be discussed. Regarding soft lenses, a daily disposable may be advantageous over reusable due to the increased ease and convenience. If handling becomes an issue, or Ben’s mother would like more control and the ability to monitor progress, then orthokeratology lenses may be preferred. The usual myopia management options and advice covering aspects such as time outdoors, lifestyle, and near work are also applicable.

Risk Factors

Ben is taking one of the most commonly prescribed medications for ADHD, and although the majority (approximately 70%) of those who take methylphenidate see improvements in ADHD symptoms,19 some appear to be at more risk of ocular side effects. Additionally, it is contraindicated for those with glaucoma. Methylphenidate is a central nervous system stimulant. It increases the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain that play a part in controlling attention and behaviour. There are some adverse ocular responses to these medications, such as blue-yellow colour vision problems.20 However other aspects – such as the increased likelihood of ocular surface pathology, namely dry eyes – when taking these medications21 are more significant. Interestingly, dry eye is only listed as a rare side effect, whereas visual disorders are more common.22 Nevertheless, it is important to take a detailed patient history and conduct a thorough ocular surface assessment for these individuals prior to a contact lens fitting.

To maximise fitting success and make the contact lens fitting journey as efficient as possible, communication is key: we need to ensure Ben is fully aware of the process. Some top tips are highlighted in Table 1.

Younger children, on average, may need slightly longer to master contact lens handling skills during the contact lens teach,23 although there is no research specific to individuals with ADHD. For Ben we need to find an approach that best suits his personality and learning style. Making the experience engaging, turning it into a game, reminding Ben of his motivation for lens wear, and linking it to the benefits are likely to be advantageous. Flexibility will be key; it may be that several visits with shorter durations for the teach and using a variety of supporting resources will provide better results. Offering a courtesy follow-up call during the first week would be a good idea.

CASE 2: TINA, AN AUTISTIC PATIENT

Autism characteristically affects communication, social interaction, and behaviour (Figure 4). These impairments have stressful impacts on the day-to-day living of people with autism.24,25 Autism is not an intellectual disability itself, but about one-third of people diagnosed as being on the spectrum have a co-existing intellectual disability.26

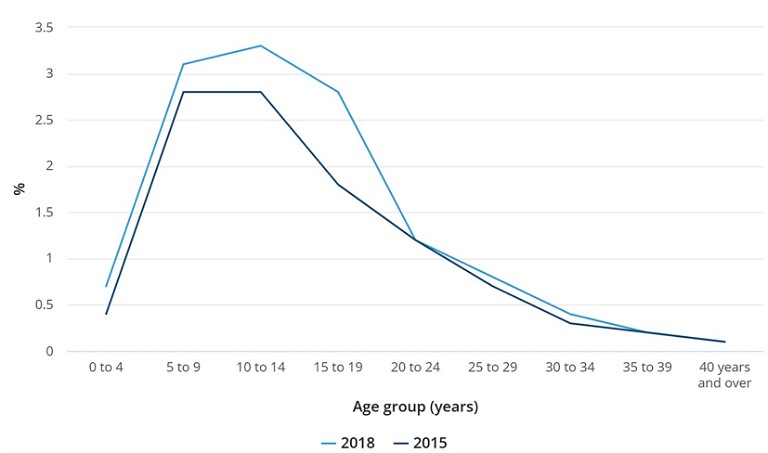

Globally, 0.6–1% of the population have ASD,27,28 and there appears to be a gender imbalance, with up to four times more males diagnosed with ASD than females.28 Prevalence levels per age group in Australia are displayed in Figure 5.29 Of interest will be whether these trends have significantly changed in the next survey data, due to be published in June this year by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

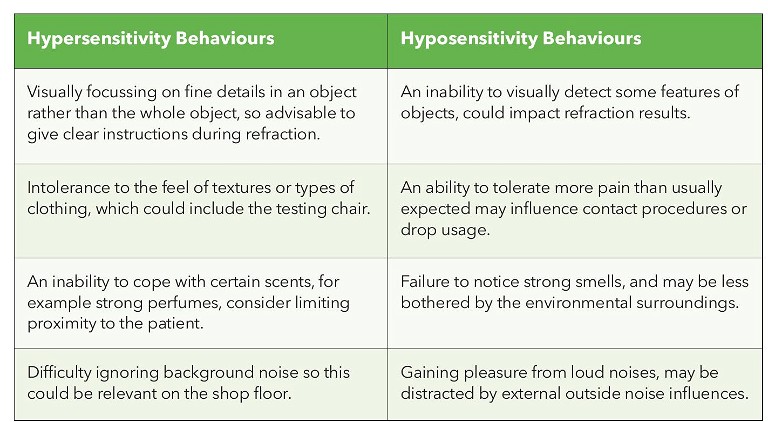

Most autistic people have altered sensory reactivity,30 meaning they experience sensory stimuli differently to other people. They can be hyper- or hypo- sensitive to sensory stimuli (Table 2), which may have an impact during eye examination and contact lens assessments.

Additionally, people with ASD can display sensory seeking behaviours, such as excessive touching of object edges or a fascination with reflections.31 Research has shown the degree of altered sensory reactivity increases with the severity of autism32 but not age.33,34 Importantly, sensory issues are lifelong, affecting each sense35 as well as multisensory processing.36 The impact of these can vary from stressful to pleasant, depending on the nature of the resultant experience.37,38

Table 2. Sensitivity related behavioural characteristics of ASD.

Autism and Vision

Although visual acuity is comparable between those with ASD and those without,39 autistic people are at greater risk of developing optometric anomalies including higher refractive errors and binocular vision anomalies (e.g., strabismus, amblyopia and accommodation problems).40,41 Additionally, some visual experiences associated with autism have been found to overlap with typical symptoms of optometric problems.42 Therefore, like individuals with ADHD, autistic people should undergo a thorough eye examination to manage any vision issues.

Autistic adults can experience a variety of visual symptoms.42 The majority are sensory and due to different aspects of light (bright, fluorescent, and spot lighting), strong colours, patterns, motion, and visual clutter. These vary from person-to-person and can occur alone or as part of a larger multisensory experience. Although most of the population probably experience some of these symptoms, autistic people experience additional challenges in daily activities, such as the ability to complete day-to-day tasks, visit public places, or use public transport. Visual sensory issues negatively impact physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing. Coping strategies can involve adapted lighting in artificially lit environments, avoiding situations that provoke visual sensory experiences, specific eyewear that prevents distraction (e.g., spectacles with thinner rims or rimless) and just trying to cope as best as possible.

Tina* is a 25-year-old vocational course student. At her last eye examination, her Rx was R&L -3.00/-0.50x10 6/5 N5. Tina mentioned that she didn’t like wearing her spectacles because of the distraction caused by the frame. She had tried various spectacle frames over the years and currently wore a thin, metal frame. The optometrist discussed the possible advantages of contact lenses with Tina.

Figure 3. An evidence-based contact lens fitting approach. It is important to maintain a good balance between currently available guidance, one’s clinical judgement, and the needs of the patient.

Figure 4. Examples of the social, communication and behavioural challenges that autistic people can experience (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Figure 5. Prevalence levels of autism in the 2018 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, compared with the 2015 survey data.29

You see a note on file that Tina has autism. She can be sensitive to bright lights and touch. Would you pursue recommending contact lenses?

Contact Lens Considerations

Tina’s case does not cast any red flags for contact lens fitting. However, noting that she has difficulties with bright lights and proximity, the eye care professional needs to consider how the clinical visit can be made more accessible. Parmar et al.41 provide a detailed list of evidence-based recommendations to make eye care more accessible for autistic people. In summary, these include:

• Grasping a basic understanding of autism and the day-to-day challenges that this population may face.

• Introducing alternative options for booking appointments, counteracting the difficulty many autistic people experience with phone calls.

• Offering appointments at quieter times of the day or spreading them across multiple visits.

• Asking patients about special requirements in advance of their appointment.

• Providing the patient with ‘what to expect during your appointment’ information, allowing them to prepare for who they will meet and what processes they will undergo.

• Minimising the number of staff and rooms involved in an appointment to minimise anxiety caused by unfamiliarity.

• Establishing a good rapport with clear, friendly communication, and being aware of how the patient is coping with the experience.

• Ensuring all the patient’s presenting concerns are addressed.

In Tina’s case, the practitioner doing the contact lens fitting appointment should introduce themselves and describe the purpose of the appointment so that Tina knows what the expected outcomes are. Tina may need some time to familiarise herself with the clinic room and to become comfortable around the practitioner.

A positive aspect of eye care is the structured nature, with most clinical tests being distinct from each other and presented in a logical sequence. Therefore, the practitioner should work through the examination routine, ensuring they explain to Tina the purpose of the test, showcasing the equipment that will be used (for example, the slit lamp). The practitioner should describe how the test will be conducted; for example, “I am going to use this microscope to have a closer look at your eyes, this will involve a bright light being shone at your eye”, and confirm that Tina understands what she will be expected to do. Good observational skills are important: if there are signs that Tina is becoming distressed or tired during the appointment, a break should be offered, clarifying if she would like to continue or take the opportunity to resume on another day.

Tina has reported difficulties with bright lights and touch, both of which are commonly encountered in eye care. Adaptions could include asking Tina to cover her eye with her hand rather than using an occluder, or to hold her own eyelids while instilling drops or applying contact lenses. Practitioners should be wary of strong smells in their clinic room, such as perfume, as this can be very difficult to cope with for some people with autism.

The brightness of lights should be adjusted or/and make use of filters/diffusers to ensure patient safety and comfort during slit lamp investigations. The practitioner should warn Tina before touching her eyelids and discuss the importance of more invasive tests (fluorescein and lid eversion assessments). If a test is only partially complete, recordkeeping should reflect this.

For Tina, the usual lens selection options and fitting assessment seem applicable. Reminding her about her motivation for contact lenses and relating them to her personal interests is likely to keep engagement high. A useful tip is to let Tina touch and feel the contact lens before beginning the fit. This will allow her to raise any concerns and you to address any misconceptions. Reassuring her that the lens will not escape around the back of her eye, and describing how it is likely to feel as gentle as a rain drop on the eye when first applied may help alleviate any initial concerns. Relating the experience of a first fit to the feel of a new watch on your arm or new pair of shoes will also help.

The contact lenses teach may typically be conducted by another member of practice staff, however, if Tina isn’t familiar with this person, she may feel anxious and not communicate as well with them. Therefore, in this case, it is ideal for the same practitioner to continue the teach with Tina, or, if unavoidable, for Tina to be warned that she will meet with different members of staff. Like many patients, Tina may require multiple visits until she is comfortable with contact lens application and removal, and a reassuring approach should be maintained. It is beneficial to schedule a courtesy follow-up call within the first week of lens wear, ideally with the same person who was involved with the contact lens teach. This will enable them to measure Tina’s progress and to provide an opportunity to offer additional support. Depending on their clinical judgement on how Tina is coping with contact lens use, the practitioner may decide to extend Tina’s trial period with extra follow-up appointments and to have more frequent aftercare recalls.

SUMMARY

In summary, given the wide range of presentations of those with neurodevelopment disorders, it is possible that you may have already fitted an individual with mild symptoms with contact lenses without realising they were neurodivergent. As well, it is fairly common for people to be unaware they have ADHD and ASD because they do not have a formal diagnosis.43,44 In reality, we should embrace the opportunity to adapt our skills and be more proactive with contact lens fitting to those suitable, through introducing the feelgood factors associated with contact lenses to all our patients.45

*Patient names changed for anonymity.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit mieducation.com/breaking-down-barriers-contactlens-wear-and-neurodevelopmental-disorders.

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental Disorders (online fact sheet), 8 June 2022, available at: who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mentaldisorders#Neurodevelopmental%20Disorders [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

2. Morris-Rosendahl, D.J., Crocq, M.A., Neurodevelopmental disorders – the history and future of a diagnostic concept, Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2020;22(1):65–72. DOI:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.1/ macrocq.

3. Francés, L., Quintero, J., Fernández, A., et al., Current state of knowledge on the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood according to the DSM-5: a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA criteria. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. Mar 31 2022;16(1):27. DOI:10.1186/s13034-022-00462-1.

4. World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health ICF, 2022. Available at: cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE learning disabilities. Available for UK users only at: cks.nice.org.uk/topics/learning-disabilities [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

6. Department of Health and Aged Care. National roadmap for improving the health of people with intellectual disability. Available at: health.gov.au/our-work/national-roadmap-for-improving-the-health-of-peoplewith-intellectual-disability [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

7. Manatū Hauora Ministry of Health, Health indicators for New Zealanders with intellectual disability. Available at: health.govt.nz/publication/health-indicators-newzealanders-intellectual-disability [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability in Australia: intellectual disability, summary. Available at: aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/intellectual-disabilityaustralia/summary [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

9. Tanna-Shah, S., Retallic, N., Health and well-being in eye care practice: Riding the emotional rollercoaster of the contact lens journey. Optician Select. 2021;2021(10):8746–1.

10. Retallic, N., It's good to talk about contact lenses. mivision, Aug 2023 (192): 40–44. Available at: mivision. com.au/2023/08/its-good-to-talk-about-contact-lenses [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

11. Optometry Board of Australia. Code of Conduct for Optometrists, available at: optometryboard.gov.au [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

12. Wolffsohn, J.S., Dumbleton K., Huntjens B., et al., CLEAR – Evidence-based contact lens practice. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 2021;44(2):368–397. DOI:10.1016/j. clae.2021.02.008.

13. ADHD Australia. About ADHD. Available at: adhdaustralia.org.au/about-adhd [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

14. Barnhardt, C., Cotter, S.A., Kulp, M.T., et al., Symptoms in children with convergence insufficiency: before and after treatment. Optom Vis Sci. Oct 2012;89(10):1512–20. DOI:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318269c8f9.

15. Ho, J.D., Lin H.C., et al., Associations between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and ocular abnormalities in children: A population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. Jun 2020;27(3):194–199. DOI:10.1 080/09286586.2019.1704795.

16. Reimelt, C., Wolff, N., Roessner, V., et al., The underestimated role of refractive error (hyperopia, myopia, and astigmatism) and strabismus in children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. Jan 2021;25(2):235–244. DOI:10.1177/1087054718808599.

17. Choudhury, R.A., Hale E.W., et al., Researching eyesight trends in ADHD (Retina). J Atten Disord. Oct 21 2023:10870547231203169. DOI:10.1177/10870547231203169.

18. Walline, J.J., Lorenz, K.O., Nichols, J.J., Longterm contact lens wear of children and teens. Eye Contact Lens. Jul 2013;39(4):283–9. DOI:10.1097/ICL.0b013e318296792c.

19. Greenhill, L.L., Pliszka, S., Dulcan, M.K., et al., Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Feb 2002;41(2 Suppl):26s-49s. DOI:10.1097/00004583-200202001-00003.

20. Bingöl-Kızıltunç, P., Yürümez, E., Atilla, H., Does methylphenidate treatment affect functional and structural ocular parameters in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? A prospective, one year follow-up study. Indian J Ophthalmol. May 2022;70(5):1664–1668. DOI:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2966_21.

21. Aydemir, E., Aydemir, G.A., Kalinli, M., Evaluation of ocular surface in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to methylphenidate treatment. Arq Bras Oftalmol. Sep 23 2022; DOI:10.5935/0004-2749.2021-0290.

22. National Health Service, Methylphenidate hydrochloride. Available at: nhs.uk/medicines/methylphenidate-children [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

23. Walline, J.J., Jones, L.A., Rah, M.J., et al., Contact lenses in pediatrics (CLIP) study: chair time and ocular health. Optom Vis Sci. Sep 2007;84(9):896–902. DOI:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181559c3c.

24. Oakley, B., Loth, E., Murphy, D.G., Autism and mood disorders. International Review of Psychiatry. 2021/04/03 2021;33(3):280–299. DOI:10.1080/09540261.2021.18 72506.

25. Uljarević, M., Katsos, N., Hudry, K., Gibson, J.L., Practitioner review: Multilingualism and neurodevelopmental disorders – an overview of recent research and discussion of clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Nov 2016;57(11):1205–1217. DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12596.

26. Iemmi, V., Knapp, M., and Ragan, Ian. (2017). The autism dividend. Reaping the rewards of better investment. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.24065.04960.

27. Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y.J., et al., Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012;5(3):160–179.

28. Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., et al., Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. May 2022;15(5):778–790. DOI:10.1002/aur.2696.

29. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data from: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC). 2018.

30. Green D., Chandler S., Baird G., Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviours in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(11):3597–3606.

31. Simmons, D., Robertson, A., Pollick, F., Vision in autism spectrum disorders. Vision Research. 2009;49(22):2705– 2739.

32. Robertson, A.E., Simmons, D.R., The relationship between sensory sensitivity and autistic traits in the general population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013/04/01 2013;43(4):775-784. DOI:10.1007/s10803-012-1608-7.

33. Kern, J., Trivedi, M., Garver, C., et al., The pattern of sensory processing abnormalities in autism. Autism. 2006;10(5):480–494.

34. Liss M., Saulnier C., Fein D., Kinsbourne M., Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism. 2006;10(2):155–172.

35.Baum, S.H., Stevenson, R.A., Wallace, M.T., Behavioral, perceptual, and neural alterations in sensory and multisensory function in autism spectrum disorder. Progress in Neurobiology. 2015;134:140–160.

36. Beker, S., Foxe, J.J., Molholm, S., Ripe for solution: Delayed development of multisensory processing in autism and its remediation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018/01/01/ 2018;84:182–192. DOI.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.008.

37. Robertson, A.E., Simmons, D.R., The sensory experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative analysis. Perception. 2015/05/01 2015;44(5):569–586. DOI:10.1068/p7833.

38. Smith, R.S., Sharp, J,. Fascination and isolation: A grounded theory exploration of unusual sensory experiences in adults with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(4):891–910.

39. Anketell, P., Saunders, K., Little, J., et al., Brief report: Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: What should clinicians expect? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(9):3041–3047.

40. Gowen, E., Porter, C., Dickinson, C., et al., Optometric and orthoptic findings in autism: a review and guidelines for working effectively with autistic adult patients during an optometric examination. Optometry in Practice. 2017;18(3):145–154.

41. Parmar, K.R., An investigation of optometric and orthoptic conditions in autistic adults. The University of Manchester; 2022.

42. Parmar, K.R., Porter, C.S., Gowen, E., et al., Visual sensory experiences from the viewpoint of autistic adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12.

43. French, B., Daley, D., Groom, M., Cassidy, S., Risks associated with undiagnosed ADHD and/ or autism: A mixed-method systematic review. J Atten Disord. Oct 2023;27(12):1393–1410. DOI:10.1177/10870547231176862.

44. Autism Research Institute, Average or high IQ in individuals with ASD may be higher than previously estimated (webpage). Available at: autism.org/averageor-high-iq-in-individuals-with-asd-may-be-higher-thanpreviously-estimated [accessed 28 Nov 2023].

45. Retallic, N., The person behind the contact lens. Optician Select. 2021;2021(9):8715–1.

Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience working in practice, education, industry, and head office roles. He currently works for the College of Optometrists in the United Kingdom and Specsavers, and is the Immediate Past President of the British Contact Lens Association.

Dr Ketan Parmar is an optometrist and lecturer in postgraduate optometry at The University of Manchester in the United Kingdom. His research includes investigating autism, vision, and accessible eye care, and has worked with autistic adults to develop recommendations for autism-friendly eye care.