mieducation

Ocular Melanoma: Empowering Patients to Take Action

As ophthalmic professionals, we have an important role to play in raising awareness and educating the community. In doing so, patients can be empowered to take positive agency of their own eye health, which we know can help improve outcomes.

Summer itself brings numerous challenges to maintaining and caring for eye health. Sadly, few members of the public are wellversed in understanding these challenges, let alone know how to effectively manage them — this is precisely where we, as professionals, can drive change and action.

WRITER Dr William Glasson

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Be aware of the need to educate patients about the importance of sun safety to eye health,

2. Understand the risks and impacts of significant sun exposure,

3. Realise the importance of early and accurate diagnosis of suspicious lesions, and

4. Be aware of the steps required to diagnose different types of ocular tumours.

As a member of the Australian Society of Ophthalmologists (ASO), my peers and I have been actively working to address gaps in public health literacy, with the summer season providing an eye-opening backdrop.

There are the issues no one is immune to, including dry eye, that can be exacerbated by frequent fan and air-conditioning exposure, as well as increased screen time, when we try to avoid the sweltering outdoor heat.

Then, there’s my typical working day, where I encounter patients whose repeated or excessive sun exposure has led to serious conditions such as pinguecula, pterygium, and cataracts.

Yet, while less common for the average Australian or New Zealander, I will more frequently see patients with ocular melanoma – the most common form of eye cancer.

Here in Australia, it’s a disease that is diagnosed on average, in 125–150 people each year. The latest data from the Cancer Council Australia suggests that more than 400 people were diagnosed in 2022, with an average age of 62 years or younger.1

While ocular melanoma may be considered a rarer form of cancer, more common skin cancers such as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) can also be found impacting in and around the eyes.

What is paramount in my daily face-to-face interactions with patients, is an inherent lack of understanding about the role of eye health in sun safety. Sadly, for some, an arrival to awareness occurs too late.

Throughout the Australian summer – and even all year round – we see UV indexes well above ‘level 3’, which is when sun safety measures are recommended to commence.

Across mainland Australia, we are currently seeing seasonal indexes within the ‘extreme’ range of 11–15, and across the ditch in New Zealand, these indexes start within the ‘very high’ range of 8–11 and reach into the ‘extreme’ range.

With our geographical position being primed for some of the world’s highest UV ratings, it reinforces the need to educate year-round prioritisation of eye health – and it starts by empowering individuals.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

As individual eye care professionals, in our daily work, we can help to further public health literacy around the Australian and New Zealand standard for sunglasses. We can advise what is – and is not – considered to be sun safe effective. And we can educate on the eye conditions and symptoms everyone should be aware of – including those that are lesser known, such as ocular melanoma.

ANZ STANDARDS

Assessed against the Australian and New Zealand Standard for sunglasses, only products with a lens category of two, three or four are recommended to provide effective UV protection. Table 1 (next page) provides a comprehensive breakdown of each lens category.

EFFECTIVE SUN SAFETY

Always reinforce that effective sun safety means taking five steps: Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, and Slide.

Table 1. Categories of sunglasses and fashion spectacles according to the Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZS 1067.1:2016.

Slip

‘Slip’ on a shirt or protective sun clothing. Select clothing that will provide as much coverage as possible, such as long sleeves and high necks. In hot weather, it is recommended to select cotton-based materials and opt for light colours as opposed to dark. It is also worth noting that some clothing carries an ultraviolet protection factor (UPF), which aims to provide a guarantee of the level of UV protection.

Slop

‘Slop’ on sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 30 or higher, that is labelled broad-spectrum and water-resistant. It is best practice to apply sunscreen to dry skin at least 20 minutes before going outside, and it should be re-applied every two hours.

Slap

‘Slap’ on a broad-brimmed hat that will provide optimum protection from radiated reflected rays. Remembering that BCCs and SCCs are also common around our eyes, always select headwear that fits appropriately and covers your face, nose, neck, and ears.

Seek

‘Seek’ shade wherever possible, by creating or finding it when outdoors. Consider using UPF-designed gazebos or umbrellas in addition to natural shade from trees.

Slide

‘Slide’ on UV-blocking eyewear. The style of the sunglasses worn is inherently important. As side light can cast unexpectedly harmful and high UV exposure onto our eyes, a wraparound style of eyewear is an essential must for all. Make sure the eyewear also meets the Australian and New Zealand Standard noted in the table above.

RISKS TO EYE HEALTH

Some of us are more at risk of the impacts of significant sun exposure.

For example, children under the age of 10 are considered high risk to develop eye damage from UV radiation, so instilling effective sun and eye safety practices early is crucial. Children within this cohort are particularly sensitive to the effects of sun exposure as the lens of their eye is clear and more vulnerable to solar penetration.

Within the adult population, excessive sun exposure over time can lead to conditions such as cataract, pinguecula and pterygium, and ocular melanoma.

Cataract

Cataract is a condition that causes clouding of the eye lens and progresses gradually over time. When left untreated, it can result in vision loss. More than 500,000 cases are diagnosed each year in Australia.

Pinguecula and Pterygium

Pinguecula and pterygium are growths that occur on the white part of the eye, known as the conjunctiva. Both conditions are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation and worsened by chronic dryness or irritation – unavoidable challenges in the Australian summer.

A pinguecula can only be found on the conjunctiva and is often a small raised whiteor yellow-coloured growth. Generally, it does not affect vision but can cause dryness, redness, and inflammation.

A pterygium grows from the conjunctiva and extends onto the cornea, known as the surface of the eye, and can occur on either side of the eye. It is commonly referred to as ‘surfer’s eye’. These growths can cause decreased or distorted vision, but more commonly present with irritation, redness or the sensation of something in the eye.

Ocular Melanoma

Ocular melanoma – also known as uveal melanoma, intraocular melanoma, or eye melanoma – is a type of eye cancer that develops in the cells of the body that produce melanin, which is the pigment that gives skin its colour.

Risk factors to developing the condition include having pale or fair complexion, light eye colour, family history of melanoma, growths on or in the eye, increasing age, and skin conditions that cause abnormal moles to grow.

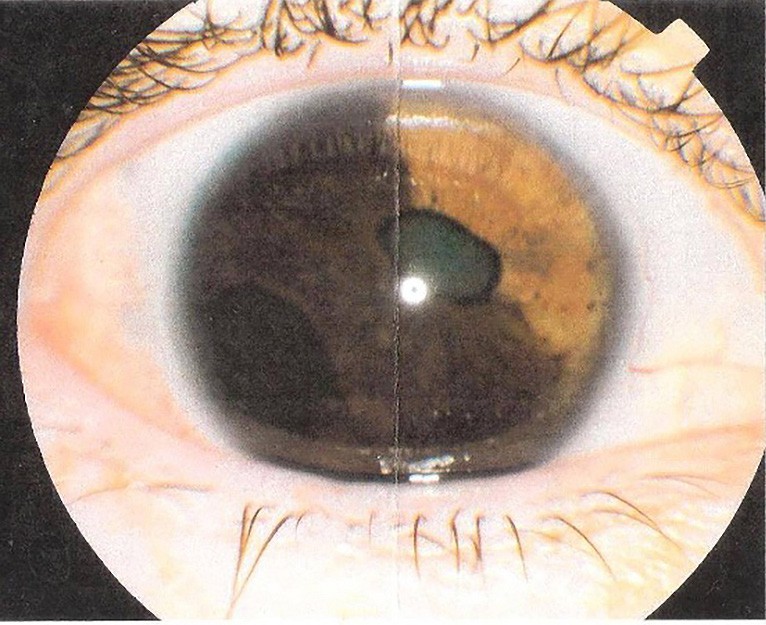

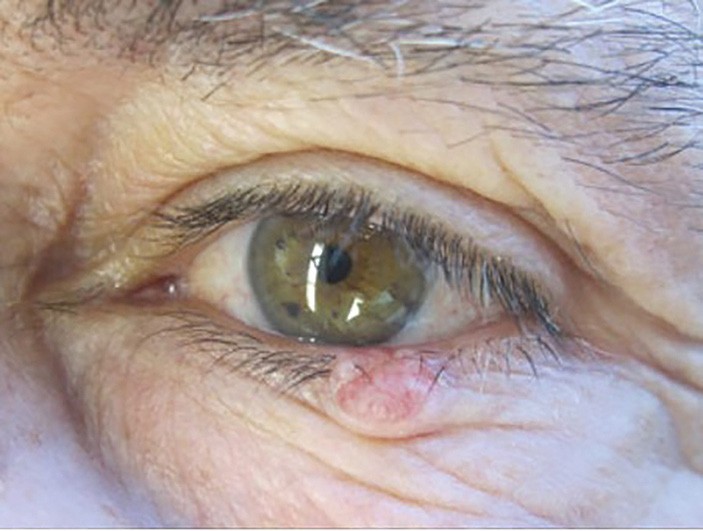

Susan Vine with ‘different coloured eyes’ prior to diagnosis of ocular melanoma.

Clinical photo of Susan Vine’s affected eye at the time of enucleation surgery.

It is worth noting that those diagnosed with pterygium are at a greater risk of developing skin cancer, including melanoma, as the condition is a marker for previous exposure to high levels of UV light.

As the condition can be difficult to see in some cases, especially if the naevus is located behind the eye, a diagnosis will often be picked up for the first time as part of your comprehensive examination of a patient.

PATIENT SUPPORT

My patient turned advocate, Susan Vine, was referred to me for an urgent consult at 37-years-old, following an eye test with an optometrist. Within two weeks of that initial eye examination, I performed an enucleation surgery completely removing her affected eye.

The route for patients is both difficult and challenging, so when it comes to a lesserknown cancer such as ocular melanoma, the right understanding and support can be difficult to find.

Identifying a chasm for support, Susan established an online support group for those navigating this path, alongside their family and friends – OcuMel Australia and New Zealand Support Group. The group has a private Facebook group and welcomes new members. You can find out more at facebook.com/groups/ OcularMelanomaAustralia.

DIAGNOSING OCULAR MELANOMA

Ocular cancers are unique among the many different diseases of the eye, with the additional ability to threaten life, as well as vision.

Ocular tumours can arise in many structures of the eye, including the eyelids, conjunctiva, and the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body, and choroid).

Although most eyelid lesions are benign – ranging from cysts and chalazions, to naevi and papillomas – the early and accurate diagnosis of suspicious lesions leads to improved patient outcomes. Pattern recognition plays an important role in the accurate diagnosis, and together with case history and clinical assessment, allows for prompt management, treatment, or further investigation.

Due to the strong correlation between BCC incidence and geographic latitude, Australia, by far, has the highest rates of skin cancers worldwide. Each year in Australia, skin cancers contribute to 80% of all newly diagnosed cancers, with the location of the eyelids accounting for 10% of these.2

Basal cell carcinomas are by far the most common malignant eyelid tumour, accounting for 90% of cases.3These types of lesions are more frequently found on the lower eyelid, followed by the medial canthus, upper eyelid, and least commonly located at the lateral canthus. They are locally invasive, but do not metastasise. However, if left untreated, lesions located at the medial canthus are prone to invade and posteriorly extend into the lacrimal system, orbit, and sinuses. The clinical features and characteristics of BCCs often conform to one of the following morphological patterns of nodular, noduloulcerative, or sclerosing, which is the least common.

On the other hand, SCCs are much less common than BCCs – accounting for 5–10% of eyelid malignancies – but are more aggressive with metastasis occurring to nearby lymph nodes in 20% of cases.

Slit lamp photography documentation and observation of the lesion are both crucial in the monitoring of lesions. There is a suspicion index for malignancy when performing lesion assessment and diagnosis, including: the area of ulceration, induration, irregular and/or pearly boarders, destruction of the eyelid margin architecture, madarosis, and telangiectasia. It is extremely important to note that eversion of the upper eyelid during examination can reveal lesions that are otherwise missed.

CONJUNCTIVAL MELANOMAS

Melanomas located in the conjunctival tissue are rare – accounting for 5% of all ocular melanomas – but are often a life-threatening cancerous growth in the eye.4 These lesions arise from melanocytes in the basal cells within the conjunctival epithelium. As it stands, due to both tumour rarity and limited population-based studies, the risk factors for conjunctival malignant melanomas are not well understood. However, there is a strong correlation between conjunctival melanomas with both primary acquired melanosis (PAM) and conjunctival naevi, and thus both differential diagnoses must be accounted for. A total of 57–76% of conjunctival melanomas arise from PAM. Therefore, it’s crucial that during anterior biomicroscopy assessment, PAM be differentiated from complexion melanosis – acondition without malignant potential. It has been reported that PAM with severe atypia can transform into a melanoma at a rate of up to 50%.5,6

A

B

Figure 1. (A) BCC with telangiectasia and madarosis and (B) SCC with central ulceration. Imagery source: www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2019/august/eyelid-lesions-in-general-practice.

A

B

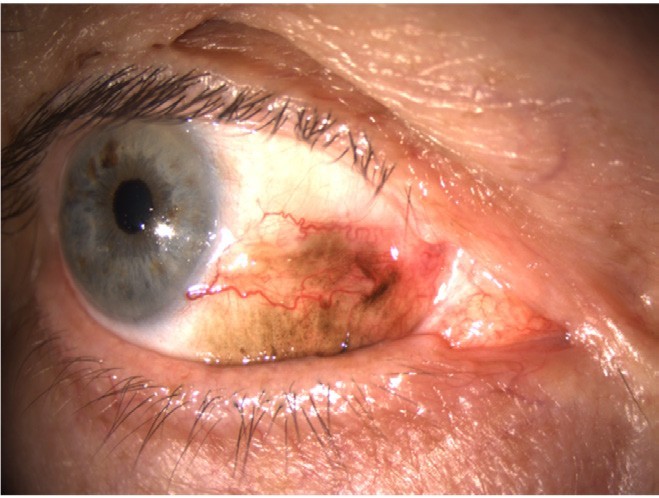

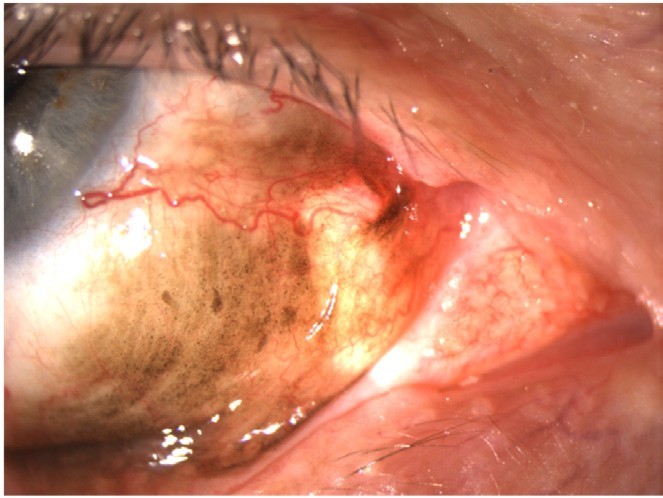

Figure 2 (A) and (B). Melanoma in situ.

Both conjunctival melanomas and PAM present in a unilateral manner. However, PAM’s differentiating features are flat, asymmetric, and non-cystic. Complexion acquired melanosis is often bilateral and diagnosed in patients with darker skin complexion.7 On the other hand, conjunctival naevi are often differentiated during case history with the patient. They are usually longstanding, unilateral, and focal pigmented lesions with cystic spaces.8

DIAGNOSIS OF CONJUNCTIVAL MELANOMA

Diagnosing conjunctival melanomas requires a clinical examination, including a thorough case history and using slit lamp biomicroscopy to carefully assess the ocular surface for any pigment, nodularity, or feeder blood vessels, and remembering to evert the lids. Any pigment on the tarsal conjunctiva should raise suspicion for conjunctival melanoma.8

Conjunctival melanoma presents as a thickened, raised, and pigmented lesion with prominent feeder vessels. It is important to note that 20% of cases may be amelanotic and are therefore often mistaken as ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) or ocular lymphoma.8 While the most common location for a conjunctival melanoma is in the bulbar conjunctiva, it is not quadrant specific. In other words, there is no area that is more commonly affected than the other. Less frequently, yet associated with worse prognosis, are conjunctival melanomas found in the palpebral and fornical conjunctiva, plica semilunaris, and caruncle regions.9 In 1% of these cases, the conjunctival melanoma may invade nearby lymphatic drainage via submandibular and preauricular lymph nodes, or through secondary structures via lesion extension to the orbit, eyelids, and nasolacrimal duct.

A final clinical diagnosis is based on case history, slit lamp biomicroscopy, and imaging.

MANAGEMENT PLAN

The first phase of the management plan is surgical wide excision (~4mm) of the lesion, combined with cryotherapy to the margins and amniotic membrane graft transplants. A surgical no-touch technique was first stated by Shields et al.,10 with the hypothesis to avoid cell seeding, dissemination, and recurrence. Adjuvant therapies include either topical chemotherapy, such as Mitomycin-C (MMC) or interferon (IFN), or radiotherapy in the form of brachytherapy. Continued monitoring for recurrence of pigment, as well as a referral to a general oncologist with scheduled magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), computerised tomography (CT) scans, and ultrasounds must be routinely performed to exclude metastasis.

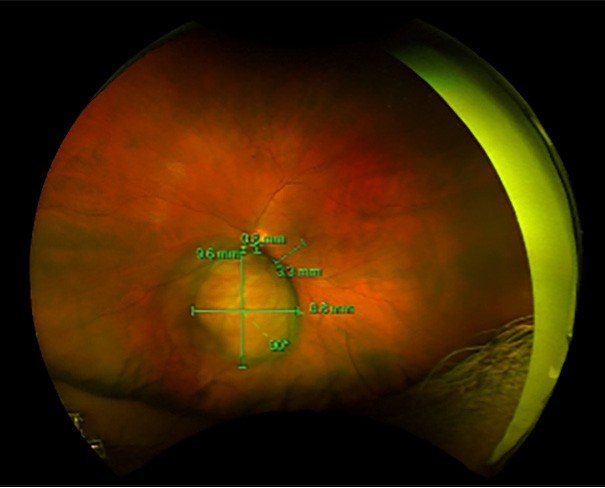

Figure 3. B-Scan ultrasound imaging representing choroidal melanoma. Measurements taken include A) depth of lesion, B) depth of lesion including scleral thickness, and C) basal dimension of lesion.

Figure 4. Wide-field imaging showing both basal dimensions of choroidal melanoma, and distances away from the optic nerve and macula.

Back before the current mainstay treatment of conjunctival melanomas, enucleation or exenteration were considered as first-line options to eradicate the melanoma.11 However, this approach was shown to provide no improvement in survival, with up to 50% mortality rates present, independent of whether total exenteration was performed as an initial or secondary treatment. Therefore, orbital exenteration is not appropriate as a primary treatment, unless the tumour has invaded the orbit, or completely involves the conjunctiva.

UVEAL MELANOMAS

Melanomas can also grow posteriorly in the uveal tract. Uveal melanomas (UM) are the most common primary intraocular tumour in adults, 12 arising from melanocytes within the stromal tissue.

Choroidal melanomas are the most common subtype of UM,13 whereas iris melanomas are the least common and have the best prognosis out of all three subtypes, often because their location is hard to miss on routine eye examinations. While ciliary body melanomas are rare, they have the worst prognosis due to the repeated contractions of the ciliary muscle and rich vascular supply of that region. Due to the location of the ciliary body and the lack of symptoms, these lesions are often diagnosed past the point of metastasis.13

Although there is no sex preference, UMs are often common in the middle-aged Caucasian population. Other risk factors of UM include fair skin, light coloured eyes, and the BAP1 tumour gene. Studies show that patients who carry the BAP1mutation are at higher risk for both uveal and cutaneous melanomas.14

Choroidal naevi are found in 8% of the Caucasian population. Risk factors, including the presence of a naevus, heightens the risk of it later progressing into a choroidal melanoma.14 Choroidal lesions are diagnosed based on several different diagnostic imaging processes, clinical assessment, and case history. Differentiating between a choroidal naevus and a choroidal melanoma is crucial in the treatment progression of the patient. Typical characteristics of choroidal melanomas include the following:

1. Symptoms: Flashes, floaters, distortion, or blurry vision. However, it is important to note that some patients with choroidal melanomas do not present with any symptoms, and that these lesions are a spontaneous find in routine optometric reviews.

2. Position: Lesions more closely located to the optic nerve or macula should raise concern.

3. Lipofuscin: This metabolic material is a product of cell death overlying the tumour that lights up on autofluorescent ultrawidefield imaging.

4. Thickness and basal dimensions: Ultrawidefield and B-scan ultrasound imaging is often used to measure the size and thickness of the choroidal lesion. Lesions >2mm are more suspicious of melanoma. Particularly, the ultrasound can measure an A-scan through the lesion to gauge internal reflectivity and evaluate for posterior extension of the lesion into the orbit.

5. Subretinal fluid: Optical coherence tomography imaging detects for any subretinal fluid that is produced by the lesion, which can cause retinal detachments and trigger symptoms.

Initial examinations and new diagnoses of indeterminate choroidal lesions or choroidal melanomas involve a whole-body PET/CT scan. Choroidal melanomas have a 90% propensity to metastasise and spread to the liver.14 Thereafter, patients benefit from sixmonthly monitoring using liver ultrasound, CT, or MRI – the latter having higher sensitivity for liver metastasis.

In brief, depending on the size and severity of the lesion, treatment and adjuvant therapies vary. Small choroidal melanomas are often treated with photodynamic laser therapy (PDT), while medium sized choroidal melanomas (<3mm) require brachytherapy radiation. Large lesions, particularly the ones that have broken through Bruch’s membrane, require enucleation surgery. This is because the amount of radiation required to destroy a large lesion will most likely be too much for the eye to tolerate.

Though choroidal melanomas are a rare intraocular tumour, if there is a failure to diagnose, the risk of death from metastatic disease can be as high as 50%. Regular optometric reviews and prompt referral to an ophthalmologist will minimise the risk of late-stage diagnosis of tumours, and therefore allow for early intervention.

To earn your CPD hours visit mieducation.com/ocularmelanoma-empowering-patients-to-take-action.

The author acknowledges the contribution of Nadine Alexander (Clinical Optometrist) and Emma Crowley (Australian Society of Ophthalmologists Media and Communications Manager) in the preparation of this article.

References available at mieducation.com

Dr William Glasson MB BS FRANZCO is a general ophthalmologist with a special interest in ocular oncology. He is currently a consultant ophthalmologist at the Mater Public Hospital, 2nd Field Hospital Enoggera, and Longreach Base Hospital. He is a past President of the Australian Medical Association and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists. He is a consultant ophthalmologist to the Australian Army and holds the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.