mieducation

BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia

Mechanism and Optics

In our continuing series, encapsulating the relevant practice conclusions from the BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia publications, Dr Sayantan Biswas and Professor Leon Davies provide an overview of the mechanism and optics associated with presbyopia.

WRITERS Dr Sayantan Biswas and Professor Leon Davies

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should:

1. Understand the mechanism of accommodation,

2. Be aware of components and factors affecting functional accommodative response,

3. Realise the effect of ageing on components of the accommodative system and visual acuity, and

4. Be aware of the theories of presbyopia.

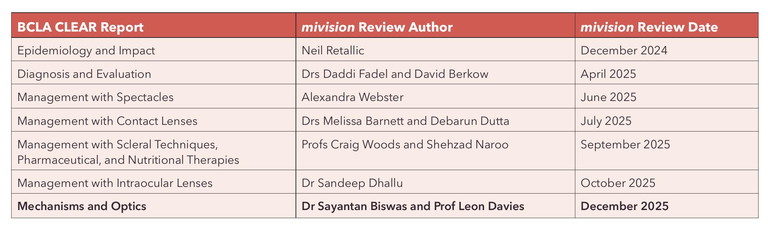

Figure 1. Schematic outline of the principal structures involved in accommodation. Left, shows the eye in the relaxed state; right, illustrates the accommodated state. Arrows indicate relative movement of structures.1

Presbyopia, a ubiquitous condition associated with ageing, affects nearly all individuals over 40 years of age. Globally, over 1.8 billion people experience this decline in near visual acuity, significantly impacting daily activities and quality of life. Despite its universal nature, the precise mechanisms underlying presbyopia have been the subject of extensive study and debate. The recently published article, BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Mechanism and Optics,1 offers a comprehensive overview of the biomechanics and optics of presbyopia. This review distils its findings, and contextualises them for clinical practice, integrating additional perspectives and controversies.

MECHANISMS UNDERLYING ACCOMMODATION AND PRESBYOPIA

Accommodation is a dynamic process that adjusts the eye’s optical power to maintain clear retinal images as fixation shifts from far to near distances.2 When focussing on distant objects (optical infinity), parallel light rays are sharply focussed on the retina. As fixation moves closer, light rays diverge, creating hyperopic blur and stimulating accommodation.

During accommodation, the ciliary muscle in the ciliary body contracts, altering zonular tension attached to the lens capsule, which alters the shape of the crystalline lens. The lens becomes optically more powerful as its curvature increases, particularly on the anterior surface, and increases in thickness. The coordinated changes in the ciliary body, zonules, and crystalline lens increase the eye’s refractive power, restoring focus and ensuring clear vision at different distances (Figure 1).

The crystalline lens consists of proteins that maintain transparency and refractive properties. The lens substrate is surrounded by a capsule that holds its structure and transmits forces from the zonules, which connect the lens to the ciliary body. The zonules adjust the lens shape, based on the contraction or relaxation of the ciliary muscle.3

Beneath the ciliary processes, ciliary muscle bundles housed within the ciliary body contract and relax to control accommodation. Along with the increase in anterior lens curvature while accommodating, the crystalline lens nucleus thickens, which increases the overall sagittal lens thickness.4 Accommodation is also linked to axial length changes, particularly in myopia, where an increase in axial length correlates with accommodation-induced changes, potentially influenced by choroidal thinning.5

The neural control of accommodation involves the autonomic nervous system, with both parasympathetic and sympathetic components playing distinct roles. In essence, the parasympathetic nervous system, mediated by acetylcholine on muscarinic receptors, stimulates the ciliary muscle to contract, relaxing the zonular fibres that suspend the crystalline lens. This allows the lens to become more convex, and increases accommodation for near vision. Withdrawal of parasympathetic input reduces accommodation.6 Sympathetic input, on the other hand, inhibits accommodation via noradrenaline acting on adrenoceptors. However, this response is slower than that of the parasympathetic system, reaching its peak effect after 10 to 40 seconds, which makes it less relevant for modifying dynamic vision tasks.6

COMPONENTS AND FACTORS AFFECTING FUNCTIONAL ACCOMMODATIVE RESPONSE

The accommodative response involves different components:7,8

Reflex accommodation. A quasi-automatic, involuntary adjustment that maintains sharp focus on a near object. It aims to maintain maximal contrast and the smallest blur circle, but it is debated whether true involuntary reflex accommodation exists.1,7

Proximal (conscious-driven) accommodation. Triggered by the knowledge of an object’s distance, without requiring changes in target size. It involves voluntary accommodation, where individuals can consciously suppress or enhance the response.

Convergence accommodation. Driven by fusion disparity vergence, this type of accommodation is used in binocular viewing to adjust focus based on eye convergence.

Tonic accommodation. A slight myopic refractive state (around 1.00D) that the eye adopts in the absence of an accommodative stimulus.

Individuals may use different cues for accommodation, such as chromatic aberration, small uncorrected astigmatism, or higher-order aberrations when primary cues are unavailable. Binocularity and disparity cues are important in real-world situations.

Amplitude of accommodation (AoA) refers to the maximum focussing range of the eye, measured as the dioptric difference between the far point (optical infinity) and the near point where an object is clearly focussed without blur. In young eyes, AoA represents the maximum accommodative effort, which decreases progressively with age. Subjective AoA tends to be higher than objective AoA measurements due to the inclusion of ocular depth of focus (DoF). This is particularly noticeable after age 45–50 years, when pupil constriction increases DoF.9

Objective AoA decreases almost linearly with age, reaching zero around 50–55 years. For real-world tasks performed binocularly, normal proximity cues facilitate convergence, which can improve accommodation, especially in younger individuals. The difference between binocular and monocular AoA measurements is about 0.6–0.7D for those up to 18 years, 0.5D for ages 18–30, and 0.4D for those aged 30–50 years.

In clinical settings, subjective methods are frequently used to assess AoA, but results can vary based on the testing protocol, and care must be taken when interpreting these results.

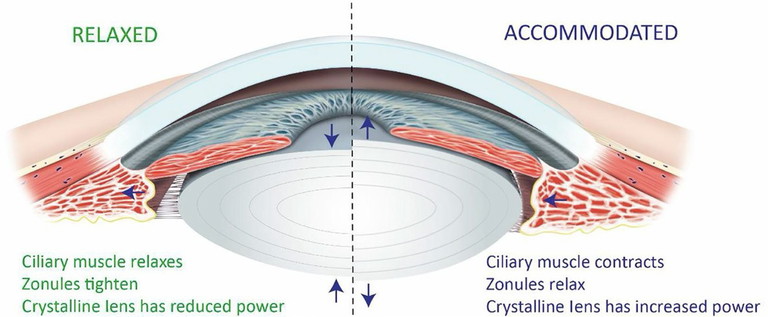

Figure 2. Accommodation response/stimulus curve from 13 young participants (age range: 23 to 33 years) under constant photopic conditions. The dashed line represents the ideal one-to-one relationship.1

ACCOMMODATIVE ACCURACY

The accommodative response, plotted as a function of various accommodative stimuli, generates the accommodative stimulus/ response curve (Figure 2). The stimulus/ response curve illustrates how accommodation deviates from the ideal one-to-one unity response, showing errors such as accommodative lead (for distant objects) and lag (for near objects).

Essentially, the stimulus/ response curve has four regions: a non-linear zone (accommodative lead), a linear zone (accommodative lag), a soft saturation zone (lag increases), and a hard saturation zone (response can no longer follow the stimulus). Errors in accommodation can lead to blurry images, but often remain within the depth of focus tolerance, so not affecting visual clarity.

The accuracy of accommodation is influenced by ocular characteristics, such as higher-order aberrations (e.g., spherical aberration), pupil size, and stimulus type (contrast, form, and size), while binocular viewing improves its accuracy.10 Accommodation errors are higher under low lighting conditions since accommodation depends largely on cone cell activity. Age-related changes also affect the stimulus/ response curve, with a reduced slope and diminished accommodation ability by around 50 years.10

Pupil diameter. Accommodation is associated with pupil constriction (miosis), which helps reduce image blur and improve visual acuity. Pupil size decreases with age, and accommodative miosis is less pronounced in younger individuals. Miosis also affects the eye’s aberrations, reducing higher-order aberrations for better visual quality.

Spherical aberration. Spherical aberration impacts accommodative accuracy. Negative spherical aberration improves accommodation response by reducing lag, while positive aberration increases lag. Ageing leads to variability in spherical aberration, affecting the accommodative response and accuracy.

Depth of field. DoF is influenced by factors such as pupil size, spherical aberration, and age, which in turn, affects the perception of blur. Errors in accommodation may not be noticeable if they are within the DoF. This complicates the measurement of AoA, as DoF can inflate clinical AoA values.

Ethnicity and environment. AoA varies across ethnic groups, with some studies suggesting earlier presbyopia onset in South East Asian populations. Environmental factors, such as exposure to solar radiation, may influence AoA, but results are inconsistent. Differences in pupil size and working distances may also contribute to accuracy.

Direction of gaze. The accommodative response varies with eye gaze direction, especially in older individuals, with downward gaze showing more significant changes (increase in AoA). However, these variations are small and generally do not require special consideration during clinical assessments.

Binocular vision. AoA is larger in binocular vision due to convergence accommodation. Differences in monocular and binocular measurements can be influenced by the individual’s phoria (eye alignment), affecting the accommodative response and lag.

These various factors influence the accuracy of the accommodative response, rendering its measurement complex and subject to individual variability.

DYNAMIC COMPONENTS OF ACCOMMODATION

Micro-fluctuation. Accommodation is not static; it exhibits micro-fluctuations in focus, ranging from 0.10D to 0.50D.11 These fluctuations consist of low-frequency components (below 0.6 Hz), linked to neurological control, and high-frequency components (1 to 2.5 Hz), associated with physiological factors, such as heartbeat. Fluctuations increase when contrast is low or when the target approaches the eye, with older eyes showing slightly reduced fluctuations, possibly due to reduced elasticity of the lens.

Accommodative response to changing stimuli. The accommodative response to change in stimuli can be assessed using step (change in accommodative response to focus objects at different distance) and ramp (characteristic of accommodative response to maintain in-focus objects moving smoothly with linearly dioptric changes) stimuli. The reaction time for shifting focus from far to near is between 226–360 m/s, while near to far takes longer. Response times are invariant with age until about 40 years old.11

EFFECT OF AGEING ON COMPONENTS OF ACCOMMODATIVE SYSTEM

Crystalline lens and capsule.2,13 The lens grows from 65 mg at birth to 250 mg by age 90 years, with increased thickness and curvature. The lens cortex thickens more than the nucleus, and its refractive index decreases over time. Despite changes in geometry, the refractive power paradoxically shifts towards hyperopia, likely due to a change in the lens’ refractive index. As the lens ages, it becomes stiffer, with glycation contributing to this stiffness, particularly in the lens capsule. This leads to reduced accommodation ability and eventual presbyopia.

Zonules. With age, zonules become less elastic, and their structure changes, leading to a forward shift in their insertion point at the lenticular capsule. This affects accommodation as the lens becomes less able to change shape with age.

Ciliary body and muscle. The ciliary muscle’s contractile ability remains intact through adulthood, but its maximum contraction declines after age 45 years. Magnetic resonance imaging studies show that the ciliary muscle continues to contract beyond presbyopia, but the ciliary muscle ring diameter decreases slightly over time. This decrease correlates with the accommodative response.14

Ciliary body elasticity. The elasticity of the ciliary muscle and choroid declines with age, limiting the forward movement of the ciliary muscle and the ability of the lens to thicken and steepen, which is critical for accommodation.

Choroid. With age, the choroid thins, especially after 40 years, which can affect retinal oxygenation and nutrient supply. The choroidal thickness decreases more rapidly between 50–70 years, and the changes in elasticity and blood flow contribute to accommodation difficulties. The choroid and ciliary body influence each other through mechanical interactions that are altered with age. Age-related stiffening can influence the movement of the ciliary muscle and, indirectly, the accommodative function.

Vitreous. As the vitreous ages, it undergoes liquefaction, where the gel-like substance becomes more liquid, weakening vitreoretinal adhesion. This process is linked to a decrease in collagen and an increase in lacunae.

Overall, these age-related changes in the crystalline lens, zonules, ciliary body, choroid, and vitreous, contribute to the gradual loss of accommodation, ultimately resulting in presbyopia and other visual impairments. The role of the vitreous in accommodation, including the posterior movement of the posterior lens pole, the forward movement of the lens, and the decrease in intraocular pressure, may be minimal since accommodation occurs in eyes post-vitrectomy.

“The progression of presbyopia is driven by a combination of biomechanical, neurological, and optical changes, with lenticular stiffening being a primary contributor”

PRESBYOPIA AND RETINAL IMAGE QUALITY

Accommodation involves a complex, coordinated process between the crystalline lens, ciliary body, zonules, and lens capsule to maintain clear vision at various distances.15 Presbyopia primarily occurs due to the gradual loss of accommodation, reducing the eye’s ability to focus on nearby objects as it ages. Accommodation depends on the interplay of lenticular and extra-lenticular components, which deteriorate with age, compromising the accommodative response.2

Optical modelling shows the impact of presbyopia on retinal image quality across different ages. Young eyes have better accommodation and clearer images at near distances, while presbyopic eyes show a sharp decline in image quality as accommodation declines. Age-related decreases in pupil size and increases in spherical aberration can slightly expand DoF, but these come at the cost of image quality. Ultimately, the combined effects of reduced accommodation, smaller pupil size, and increased spherical aberration result in a gradual decline in image quality for presbyopic individuals.

THEORIES OF PRESBYOPIA

Presbyopia theories focus on the physiological changes in the eye, like lens stiffness, and its geometry, which lead to a decline in accommodative ability with age:16,17

Lenticular theories. These theories focus on changes in the crystalline lens, particularly its increasing stiffness and thickness with age, which reduce its ability to change shape. The Hess-Gullstrand model proposes that the ciliary muscle maintains its contractile force despite ageing, but the lens becomes too inelastic for normal accommodation. This theory is supported by studies showing that ciliary muscle function is largely maintained, even in presbyopia, but lens stiffness is the primary correlate.

Extra-lenticular theories. These theories suggest that other parts of the eye, such as the ciliary muscle or the zonules, contribute to presbyopia. The Duane-Fincham model attributes presbyopia to weakening of the ciliary muscle with age, which leads to a faster decline in accommodative ability. Another theory suggests that lens or capsular ageing change increases the demand on ciliary muscle contractile strength required for a unit change in accommodation.

Geometric theories. These theories focus on the mechanical changes in the lens and its supporting structures, such as the zonules. With age, the lens thickens, and the insertion points of the zonules move further apart, reducing their effectiveness in accommodation.

Modified geometric theory. This theory suggests that changes in lens geometry, such as lens thickening and forward movement, lead to a weakening of zonular tension. It acknowledges lens thickening and a reduction in circumlental space (between the ciliary muscle inner apex and lens) as factors contributing towards reduced zonular tension, which is ineffective in changing lens shape.

No single theory can fully explain presbyopia, but it is likely due to a combination of changes in the lens, ciliary muscle, and other ocular extra-lenticular structures. The prevailing view is that lens stiffness plays the dominant role in the onset of presbyopia, with other factors contributing to the condition.

KEY CLINICAL POINTS

Presbyopia is multifactorial. While crystalline lens stiffening is a primary contributor, presbyopia involves changes in the ciliary muscle, zonules, and choroid. Eye care practitioners should consider the full accommodative system when advising patients on correction options.

Age-related changes in the ciliary muscle do not prevent contraction. Despite presbyopia progression, the ciliary muscle retains its ability to contract well into older age. This supports the potential for pharmacological or surgical interventions aimed at restoring accommodation.

Depth of focus and pupil size play a role in functional vision. Smaller pupils (due to age-related miosis) can enhance DoF, compensating for some loss of accommodation. This should be considered when prescribing multifocal or extended depth of focus (EDOF) contact lenses.

Choroidal and axial length changes in presbyopes. Axial elongation during accommodation decreases with age, likely due to choroidal stiffening.

Objective tools should be used to assess accommodation beyond subjective methods. Traditional subjective amplitude of accommodation tests can overestimate true accommodative ability. Eye care practitioners should integrate objective techniques (e.g., autorefractors, aberrometry, optical coherence tomography) for a more accurate assessment.

Future treatments may extend beyond spectacles and contact lenses. Emerging therapies, such as pharmacological agents to increase lens flexibility or surgical approaches to restore accommodation, are under investigation. Eye care practitioners should stay informed about these advancements to provide up-to-date patient care.

CONCLUSION

Presbyopia remains a complex and multifactorial age-related condition, affecting over a billion individuals worldwide. While the crystalline lens and ciliary body play pivotal roles in accommodation, evidence underscores the contributions of extra-lenticular structures. Research has historically focussed on isolated factors, resulting in a fragmented understanding of the accommodative system.

The progression of presbyopia is driven by a combination of biomechanical, neurological, and optical changes, with lenticular stiffening being a primary contributor. However, factors such as accommodative lag, pupil dynamics, and variations in depth of focus further complicate its impact on visual performance. Given presbyopia’s profound effects on daily life, a patient-centric approach is essential for effective management.

Innovations in diagnostics, therapeutics, and optical corrections continue to refine treatment strategies. Nevertheless, challenges remain, including the need for standardised assessment methods and a deeper exploration of dynamic accommodation changes. Future research must integrate both lenticular and extra-lenticular perspectives to advance toward a holistic solution. With continued progress, restoring functional accommodation and enhancing visual quality may become tangible goals in presbyopia management.

Acknowledgement and recognition to the authors of the original paper: Leon N Davies, Sayantan Biswas, Mark Bullimore, Fiona Cruickshankc, Jose J Estevez, Safal Khanal, Pete Kollbaum, Remy Marcotte-Collard, Giancarlo Montani, Sotiris Plainis, Kathyn Richdale, Patrick Simard, and James S Wolffsohn.

The paper is open access and available at BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Mechanism and optics (contactlensjournal.com). The report can also be accessed with the QR code.

This initiative was facilitated by the BCLA, with financial support by way of educational grants provided by Alcon, Bausch and Lomb, CooperVision, EssilorLuxottica, and Johnson and Johnson Vision.

The editors for this article series are Neil Retallic and Dr Debarun Dutta.

References

1. Davies LN, Biswas S, Wolffsohn JS, et al. BCLA CLEAR presbyopia: Mechanism and optics. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2024 Aug;47(4):102185. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2024.102185.

2. Charman WN. The eye in focus: accommodation and presbyopia. Clin Exp Optom. 2008 May;91(3):207-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2008.00256.x.

3. Sheppard AL, Evans CJDavies LN. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of the phakic crystalline lens during accommodation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Jun 1;52(6):3689-97. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6805.

4. Davies LN, Dunne MC, Gibson GA, Wolffsohn JS. Vergence analysis reveals the influence of axial distances on accommodation with age and axial ametropia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2010 Jul;30(4):371-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2010.00749.x.

5. Mallen EA, Kashyap P, Hampson KM. Transient Axial length change during the accommodation response in young adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 Mar;47(3):1251-4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1086.

6. Gilmartin B. A review of the role of sympathetic innervation of the ciliary muscle in ocular accommodation. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1986;6(1):23-37. PMID: 2872644.

7. Rosenfield M, Ciuffreda KJ, Hung GK, Gilmartin B. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1993 Jul;13(3):266-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1993.tb00469.x.

8. Rosenfield M, Ciuffreda KJ, Hung GK, Gilmartin B. Tonic accommodation: a review. II. Accommodative adaptation and clinical aspects. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1994 Jul;14(3):265-77. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1994.tb00007.x.

9. Burns DH, Allen PM, Edgar DF, Evans BJW. A review of depth of focus in measurement of the amplitude of accommodation. Vision (Basel). 2018 Sep 6;2(3):37. doi: 10.3390/vision2030037.

10. Charman W. Optics of the eye. In: Handbook of Optics: Vision and Vision Optics Vol 3 (Bass M, Enoch I, Lakshminarayanan V, editors). New York: McGraw Hill LLC, 2010.

11. Charman WN, Heron G. Fluctuations in accommodation: a review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1988;8(2):153-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1988.tb01031.x.

12. Wolffsohn JS, Sheppard AL, Vakani S, Davies LN. Accommodative amplitude required for sustained near work. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011 Sep;31(5):480-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00847.x.

13. Mordi JA, Ciuffreda KJ. Dynamic aspects of accommodation: age and presbyopia. Vision Res. 2004 Mar;44(6):591-601. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2003.07.014.

14. Sheppard AL, Davies LN. The effect of ageing on in vivo human ciliary muscle morphology and contractility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Mar 28;52(3):1809-16. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6447.

15. Buehren T, Collins MJ. Accommodation stimulus-response function and retinal image quality. Vision Res. 2006 May;46(10):1633-45. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.06.009.

16. Atchison DA. Accommodation and presbyopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1995 Jul;15(4):255-72. PMID: 7667018.

17. Strenk SA, Strenk LM, Koretz JF. The mechanism of presbyopia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005 May;24(3):379-93. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.11.001.

Dr Sayantan Biswas Phd MPhil Optom BPhil Optom is a lecturer in optometry at Aston University with a strong track record in vision science research. He has authored over 40 peer-reviewed publications and secured research funding from charitable foundations and multinational organisations. Dr Biswas serves on the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Annual Meeting Program Committee (Anatomy Section), is an editorial board member for Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, and Scientific Reports, and a reviewer for leading journals, ethics committees, and funding bodies in ophthalmic and vision sciences. His research primarily explores myopia and the influence of visual and environmental factors on its development and progression.

Professor Leon N Davies FCOptom is Professor of Optometry and Physiological Optics at Aston University. He is Chair of the Board of Trustees and Immediate Past President of the College of Optometrists, and a Senior Court Assistant of The Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers. With over 70 peer-reviewed publications and more than £3 million in research funding, his work in physiological optics, particularly on presbyopia and restoring ocular accommodation in ageing eyes, has earned international recognition. He is a recipient of the College of Optometrists Research Fellowship Award and the inaugural Neil Charman Medal for excellence in optometry, optics, and vision science.