mieyecare

Inherited Retinal Disorders

Misdiagnosed as Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Pegcetacoplan (Syfovre), a complement 3 inhibitor, was recently approved by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for treatment of geographic atrophy (GA),1 secondary to age-related macular degeneration (AMD), based on landmark clinical trials.2 Clinical diagnosis of GA is based on history and examination. However, there are phenotypical similarities between AMD and other diseases, such as inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), which can decrease clarity of diagnosis.3,4 As different treatments for both GA and IRD are either now available or in development, accurate diagnosis has become more important.

WRITERS Dr Demi Markakis, Dr Alexis 'Ceecee' Britten-Jones, Professor Lauren Ayton, and Associate Professor Heather Mack AM.

CASE HISTORY

John Newman,* a 66-year-old white male presented in 2011 with slow, painless loss of vision in both eyes. His medical history included hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and a mixed motor and sensory peripheral neuropathy. His regular medications included olmesartan/ amlodipine, fenofibrate, and paracetamol. He reported no smoking history. His past ophthalmic history included right amblyopia treated by occlusion in childhood. Mr Newman reported a family ophthalmic history of a maternal uncle with poor vision.

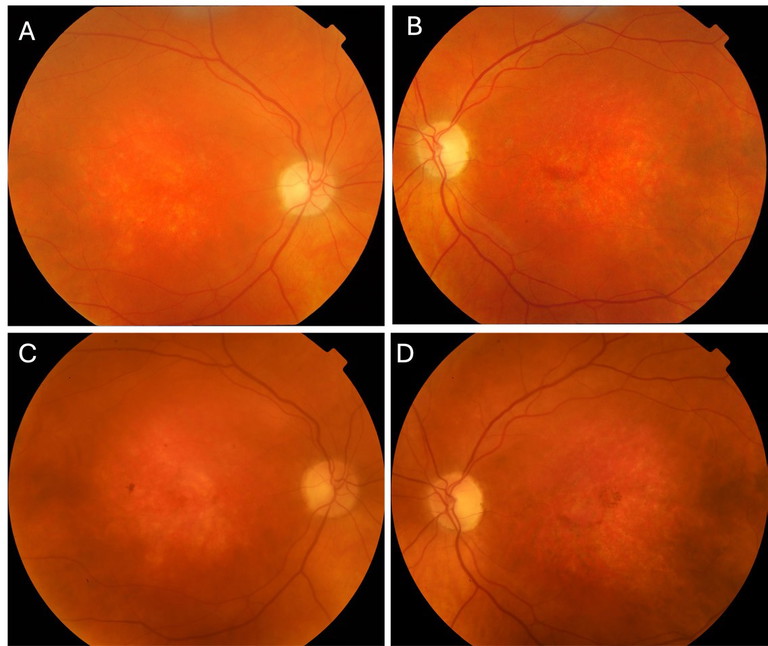

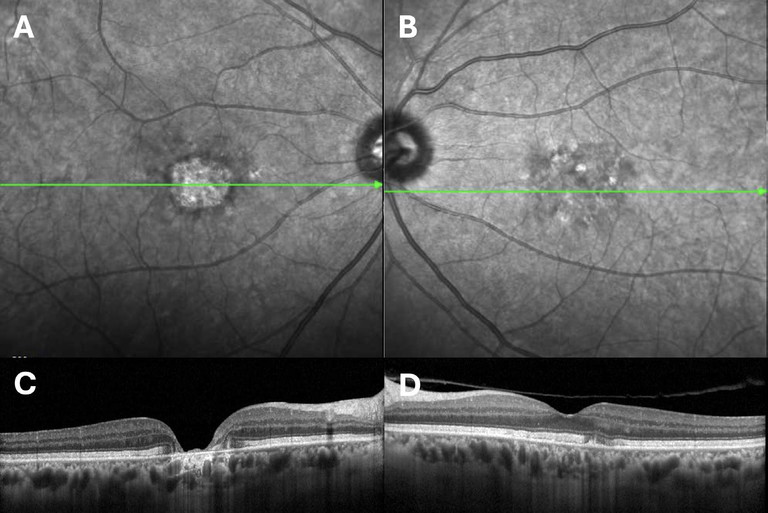

On initial examination, best corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were right 6/120, left 6/38. Slit lamp examination revealed cortical cataract in both eyes. Optic discs were cupped 0.2 with disc pallor, retinal arterioles were attenuated, and maculae showed diffuse thinning. The peripheral retina was normal in both eyes (Figures 1A and B). Ishihara test plate was failed in both eyes.

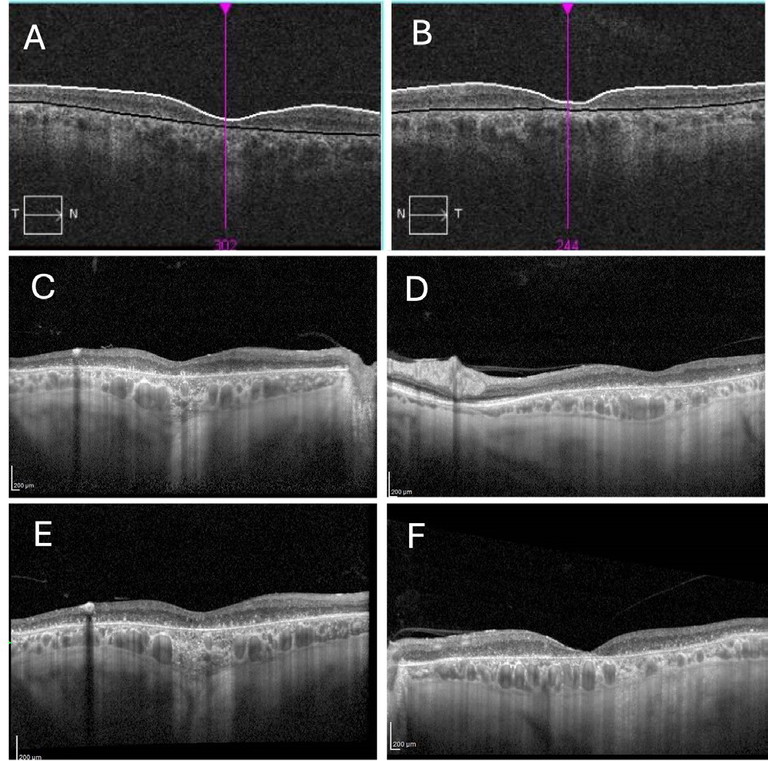

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scanning demonstrated average retinal nerve fibre thickness: right 71, left 69 µm. Macular OCT scanning demonstrated thinning of all retinal layers in both eyes (Figures 2A and B).

Full-field electroretinogram (ERG) showed markedly reduced amplitude and delayed latency in scotopic 0.01 cd.s.m-2(candela second per square meter) responses. Bright-flash dark-adapted 10 cd.s.m-2responses also showed negative morphology. Photopic 3.0 cd.s.m-2responses showed reduced amplitude and delayed latency. Full-field ERG demonstrated both generalised dysfunction of both rods and cones and inner retinal dysfunction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain reported “moderate cerebral and mild brain stem small vessel ischaemic change. No optic nerve or orbital lesion”.

At presentation in 2011, Mr Newman was diagnosed with GA with incidental negative ERG of uncertain significance. This prompted further investigation into prior neurological and ophthalmological history.

Past records from a tertiary hospital in 1991 noted BCVA 6/18 bilaterally. He failed Ishihara test plate in both eyes. Disc pallor was noted, along with “minimal disturbance of the macula”. Visual evoked potential testing was reported as marked delay in P100 responses (right 142 msec, left 144 msec), suggesting slowed conduction in the anterior visual pathways. He was diagnosed with bilateral optic atrophy of unknown aetiology. Follow-up in this tertiary hospital in 1996 recorded BCVA right 6/36, left 6/18 with bilateral disc pallor and mottled foveae. Full-field ERG was reported as “borderline reduced”. At this stage, a diagnosis was made of “probably sporadic optic atrophy… not Leber hereditary optic neuropathy”.

Mr Newman was reviewed biennially after 2011 with stable clinical findings (Figures 1C and D, Figures 2C and D). During review in 2016, he mentioned that his two-year-old grandson, birthed by his daughter, was undergoing investigation for reduced visual acuity. Macular and peripheral retinoschisis was noted during his grandson’s examination under anaesthetic. Sequencing of the RS1 gene demonstrated a pathogenic mutation, hemizygous in-frame deletion of c.496_498delTAC (p.TYR166del), associated with X-linked retinoschisis (XLRS). Based on family history, the patient’s diagnosis was revised to XLRS.

At last review in 2025, BCVA were right 6/60 and left 6/48. Clinical findings remained unaltered (Figures 2E and F).

Figure 1. Colour fundus photography of the right and left eyes respectively on serial assessments. A) and B) 2011; C) and D) 2021.

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography findings of the right and left eyes respectively. A) and B) 2011; C) and D) 2021; E) and F) 2025.

DISCUSSION

AMD, Drusen in Diagnosis, and Current Treatments

Clinical diagnosis of AMD is based on Beckman criteria, with drusen deposits >63 μm in diameter the heralding feature.5 Drusen are rounded deposits composed of extracellular debris, lipid-rich materials, and protein, elevating the basal lamina of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) from the inner layer of Bruch’s membrane. Other key features of AMD include RPE pigmentation changes from degeneration or migration, and later stage sequelae such as GA or choroidal neovascularisation (CNV).3 No genetic confirmation is available for AMD.

Reticular pseudodrusen (RPD) represent a clinically distinct entity of drusen, anatomically delineated from standard drusen due to their location above the RPE. While detection of RPD in a patient with AMD is associated with advanced disease,6 the RPD phenotype is not limited to AMD alone and can be associated with Sorsby fundus dystrophy,7 autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy pseudoxanthoma elasticum associated with mutation in C1QTNF8, and extensive macular atrophy with 9, 10 pseudodrusen-like appearance (EMAP).

Late-stage complications of AMD are neovascular AMD and GA, both potentially resulting in loss of central vision. Neovascular AMD is treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections.11 GA is the more common end-stage of disease, characterised by loss of photoreceptors, choriocapillaris, and disruption of the RPE, possibly due to chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. This manifests on colour fundus photography as a pale lesion with well-defined edges,12 or hypertransmission below the retina with attenuation of the RPE and photoreceptor bands on OCT.13 Complement 3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan was approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (but not the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme) and introduced into Australian ophthalmology practice earlier this year, based on clinical trials demonstrating safely slowing GA progression.1,2 Further complement-based treatments, including complement 5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol, are being utilised in the United States, and have been approved for use in Japan.14-16 Avacincaptad pegol was approved for treating GA in Australia by the TGA in October this year.

IRD PHENOCOPIES OF AMD

Although AMD represents a distinctive disease process, appearances of GA, especially after drusen regression, can pose a ‘phenocopy’ and masquerade as other retinal pathologies, including IRDs. IRDs currently encompass over 350 loci or genetic mutations17 and clinical manifestations are very varied.

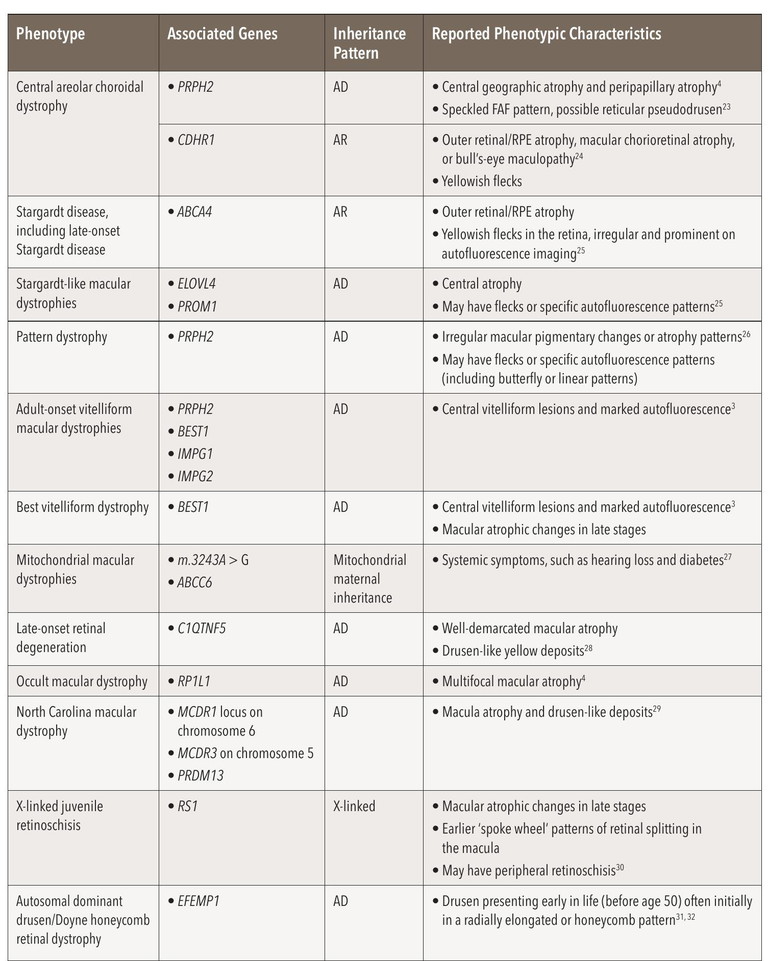

Occasionally IRDs have a pathognomonic appearance, including the para-arteriolar sparing of atrophy associated with CRB1-associated preserved paraarteriolar RPE (PPRPE), a distinct form of early onset rod cone dystrophy,18-20 and vitelliform macular lesions in Best macular dystrophy.21 However most IRD – including retinitis pigmentosa (RP), macular dystrophy, and late macular atrophy phenotypes – are associated with pathogenic variants in multiple genes. Common IRDs, with similar phenotypic characteristics to atrophic AMD, are shown in Table 1 from our earlier work.22 IRDs may also demonstrate clinical features that mimic drusen, posing further challenges to clinical diagnosis.3 Examples of IRDs phenocopying AMD, although not exhaustive, are discussed below.

ABCA4 Retinopathies

The ABCA4 gene is responsible for production of the ABCA4 protein, which plays a key role in photopigment recycling, preventing accumulation of lipofuscin that is toxic to the retina. Mutations are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and manifest as different clinical phenotypes, known as ABCA4 retinopathies, including Stargardt macular dystrophy, cone dystrophy, and cone-rod dystrophy. Mutations in this gene may also predispose to AMD.33 Due to gene complexity, determining the pathogenicity of identified variants can be challenging.

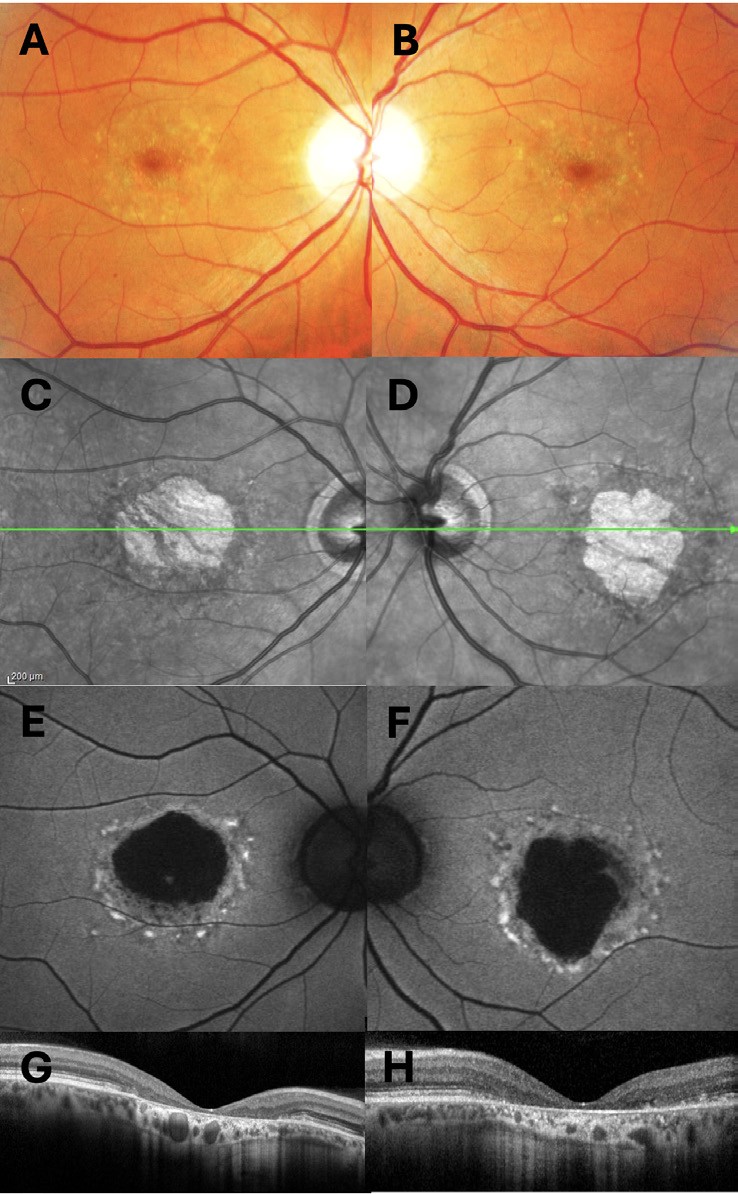

In Stargardt disease, the macula is typically affected in childhood; onset later in life is also described. The associated RPE disruption and pigmentary changes may resemble AMD (Figure 3). Flecks will usually precede atrophy and resorption, similar to drusen. Flecks also have increased signal on autofluorescence, however are histologically located primarily at the level of the RPE and differ in morphology compared to drusen with irregular appearances.34,35 Treatments for Stargardt macular dystrophy are currently in development.36

Figure 3. A 56-year-old white male with heterozygous ABCA4 variants c.5882G>A (p.Gly1961Glu) pathogenic, low penetrance and c.2927T>C (p.Leu976Pro) variant of uncertain significance. A) and B) colour fundus photographs of the right and left eye; C) and D) infrared images of the right and left eyes; E) and F) blue-light fundus autofluorescence images, G) and H) optical coherence tomography scans of the right and left maculae.

Table 1: Common inherited macular dystrophies with similar phenotypic characteristics to atrophic age-related macular degeneration. Abbreviations: AD=Autosomal dominant; AR=autosomal recessive.

Figure 4. A 61-year-old white male with a heterozygous variant in PRPH2 c.863dup; pSerVaifs*12, classified as pathogenic. A) and B) infrared photographs of the right and left eyes; C) and D) optical coherence tomography scans of the right and left maculae.

Pattern Dystrophies

Pattern dystrophies represent a number of conditions, including adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy (AVFM). The commonest affected gene is PRPH2.37 They typically present in earlier midlife with RPE pigment changes and in AVFM with an early-onset vitelliform lesion in lieu. Patients can develop regions of macular GA mimicking AMD (Figure 4). Pattern dystrophies are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Similar to RP, syndromic pattern dystrophies are recognised and are clinically important to identify.38

X-Linked Retinoschisis

XLRS is associated with a defect in RS1, a sex-linked gene, which leads to an increase in prevalence in males compared to females.39 The gene encodes retinoschisin protein, which is responsible for cellular adhesion. Patients with X-linked retinoschisis usually present early in life, often school-age with poor vision. Family history is common in male relatives, although there can be variations in disease progression and severity, even within the same family. Early examination often demonstrates schisis cavities within radial folds in the fovea. XLRS typically demonstrates intraretinal cystic retinal spaces secondary to peripheral retinal splitting, however this was not demonstrated in our case. In the mid-life period, schisis can resolve with further development of pigmentary changes and RPE atrophy similar to GA (Figures 1 and 2). Negative ERG is usually present in X-linked retinoschisis associated with impaired transmission of electrical impulses between photoreceptors to bipolar cells secondary to schisis. Definitive diagnosis is made by targeted gene testing or exome sequencing. Gene therapy is currently in development.40

EFEMP1-Associated Autosomal Dominant Drusen

A rare allelic condition, this condition is known as Doyne honeycomb retinal dystrophy (DHRD) and characterised by drusenoid deposits around the macula and optic nerve. Alike AMD, these are usually located below the RPE, although differ in morphology: smaller drusen are more elongated while larger drusen aggregate in the peri-macular and disc regions. Unlike AMD, large drusen associated with DHRD tend to hyperautofluoresce. With progression of the disease, drusen can begin to coalesce, leading to pigmentary and atrophic changes, and in some cases, develop CNV similar to AMD.3,31,32

LESSONS IN PRACTICE: WHEN TO SUSPECT IRD

The overlap between clinical features in IRDs and atrophic AMD makes delineation of these two diseases challenging. We recently found about 1.9% rate of misdiagnosis of patients with GA using clinical assessment.41 Genetic testing can provide a definitive diagnosis of a pathogenic mutation diagnostic of IRD in about 60% of cases,42 but there is no available genetic test for AMD. Access to genetic testing is limited in Australia, with considerable unmet need,43 and patients may not always take up testing when offered.44 Clinical judgement is required to diagnose IRD when phenotypes vary from textbook patterns. While the rate of patients diagnosed with AMD but suspected to have IRD is low, this represents a lost opportunity to appropriately treat and change the course of vision loss for patients with both AMD and IRD, among a backdrop of emerging treatments.41

Clinical assessments provide only a single snapshot of a patient’s overall disease. While IRD is associated with younger age, clinicians must be aware that even patients presenting within their fifth decade or beyond may have late-presenting IRD. Absence of drusen is confounding, they may have resorbed or never been present. Other key features include reduction in colour vision (which is not specific to dystrophies, but more likely – especially in cone dystrophies – compared to AMD) and family history, which was displayed in the case study presented in this article.3,4 Multi-modal imaging is increasingly used in diagnosis of retinal disease,45,46 but this was not widely available until recently, and not always helpful in presentations of atrophy only, when diagnostic features such as drusen or schisis cavities have resorbed.

Our case demonstrates the difficulties that can occur in accurate diagnosis of inherited retinal disease, with misdiagnoses of optic neuropathy and AMD over the patient’s lifetime. Clinical testing tools, such as fundus imaging and ERGs may be similar in both disease types, despite having distinctly different pathogenesis, particularly in late-stage disease.3,4,47 Final diagnosis in this case was made by genetic testing of an affected grandson.

CONCLUSION

There are risks inherent in clinical diagnoses used to make treatment-defining decisions and for counselling patients. For example, in this case, treating GA with newly introduced complement inhibitors or optic neuropathy with nutritional supplements. Errors in diagnosis risk inducing unnecessary costs or exposing patients to side effects with unproven treatment benefits. Importantly, situations like these represent missed opportunities to treat, given that gene therapy for RS1 pathogenic mutation is currently in development, as well as a missed opportunity to offer genetic counselling.

Clinician awareness of IRD masquerades of AMD is imperative in identifying diagnostically challenging cases for further discussion with colleagues or consideration of further diagnostic measures, such as genetic testing.

*Patient name changed for anonymity; written informed consent for publication of all retinal images was provided to the authors.

Dr Demi E Markakis MD is a second-year medical graduate at The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne who is interested in a career in ophthalmology.

Dr Alexis ‘Ceecee’ Britten-Jones BOptom (Hons) PhD is a Senior Research Fellow in Ocular Genomics at the Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences, the University of Melbourne, and at the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

Professor Lauren N Ayton BOptom PhD GCOT FAAO currently holds dual appointments between the Departments of Optometry and Vision Sciences and Surgery (Ophthalmology) at the University of Melbourne and the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

Associate Professor Heather G Mack AM BMedSc MBBS MBA PhD FRANZCO FRACS FAICD is an Honorary Researcher at the Centre for Eye Research Australia. She is also a Principal Associate at Eye Surgery Associates in Melbourne.

References available at mivision.com.au.