miophthalmology

Practical Analogies for Patient-Friendly Retinal Consultations

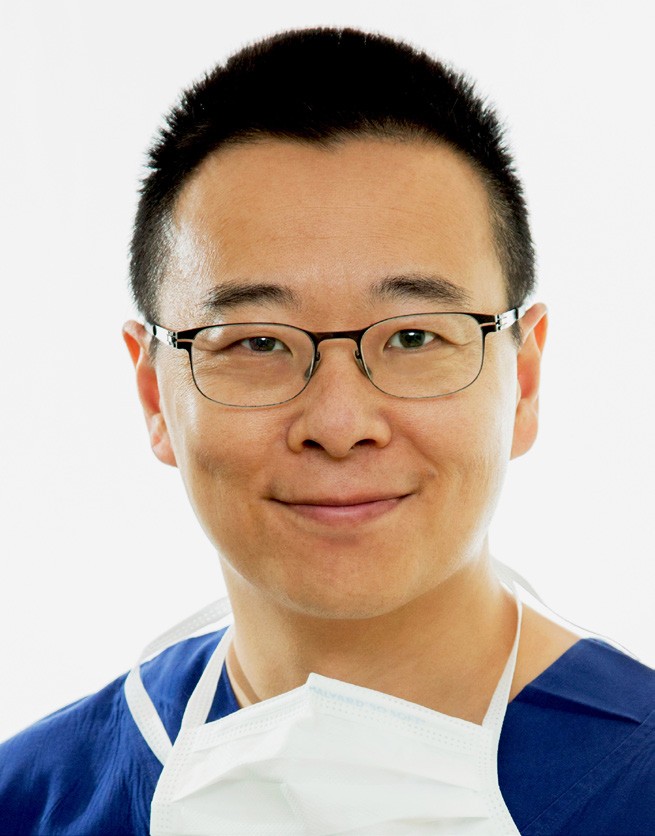

WRITER Dr Simon Chen

In a busy clinic, explaining complex retinal conditions can be challenging. This article provides a practical toolkit of analogies and conversation starters to enhance patient understanding, build trust, and streamline co-management.

THE POWER OF A GOOD STORY

In the course of a retinal consultation, a patient’s world can blur with uncertainty. We describe complex, invisible processes occurring on a microscopic scale at the back of the eye, where the stakes are high and terms, such as ‘macula’, ‘vitrectomy’, and ‘anti-VEGF’ are profoundly foreign. It is little wonder that conditions such as epiretinal membrane (ERM), macular holes, or neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) can seem abstract and frightening, leaving patients both confused and anxious.

The increasing availability of advanced retinal imaging tools, especially optical coherence tomography (OCT) and retinal cameras, means these conversations are happening earlier and more frequently, placing optometrists at the forefront of patient education.

Over years as a retinal surgeon, I have found that optimal patient outcomes depend not only on clinical expertise, but also on translating complex information into clear, relatable concepts. Carefully chosen analogies can transform daunting technical conversations into meaningful discussions where patients understand their condition, the treatment rationale, and the ongoing role of their optometrist. By turning a diagnosis into a story a patient can follow, we empower them, improve confidence in shared recommendations, and enhance the quality of care.

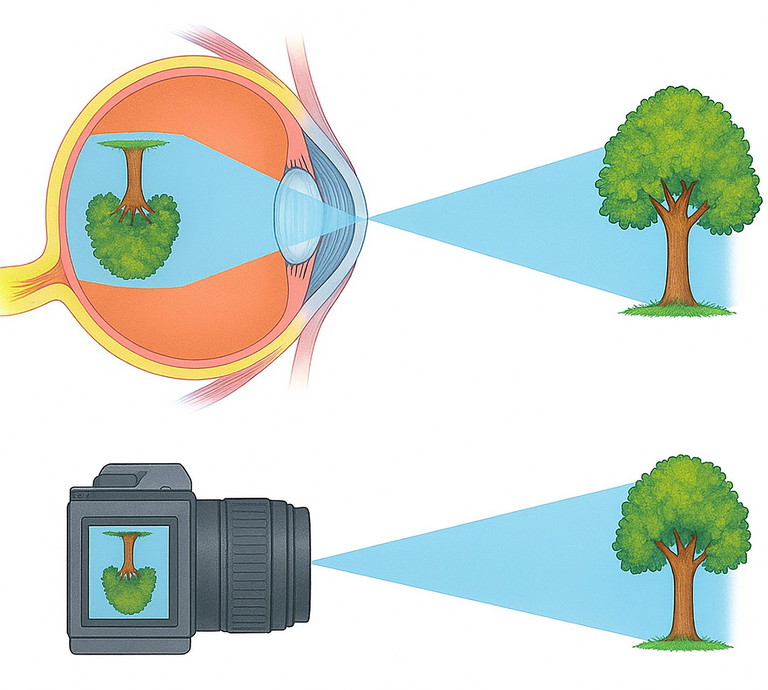

Figure 1. Camera analogy. The cornea and lens focus light from a distant object into a sharp inverted image on the retina, just as a camera lens focusses onto the sensor.

FOUNDATIONAL ANALOGIES FOR PATIENT UNDERSTANDING

The Camera Comparison

The eye as a camera is an analogy most patients instantly understand. The retina is the film or digital sensor, converting light into signals the brain interprets (Figure 1). The macula is the most sensitive central part of the sensor, responsible for high-definition vision needed for reading and recognising faces. The peripheral retina provides a wide-angle view for navigation.

This framing clarifies why macular conditions cause central vision loss while sparing peripheral sight. It also sets up discussions about interventions: a cataract is a cloudy lens that needs replacing, whereas retinal surgery repairs the sensor when damaged.

“optimal patient outcomes depend not only on clinical expertise but also on translating complex information into clear, relatable concepts”

Figure 2. The keyhole analogy for dilation or ultra-widefield imaging. A keyhole provides a limited view, much like looking through an undilated pupil, whereas an open door provides a much wider view, much like dilation or ultra-widefield imaging.

The Importance of a Complete Examination

When patients hesitate about dilation or retinal imaging, simple analogies help.

The car mechanic analogy. Not dilating pupils is like taking your car to a mechanic for a strange engine noise, but not letting them open the bonnet. They cannot fully diagnose the problem without seeing the engine.

The keyhole analogy. Looking through an undilated pupil is like inspecting an entire room through its keyhole. You can see what is directly in front, but the corners remain dark. The peripheral retina, where small tears often hide, is invisible this way. A dilated retinal examination, or an ultrawidefield scan, is like opening the door fully so the entire room is visible and nothing important is missed (Figure 2).

Technology in Consultations: Show and Tell with OCT

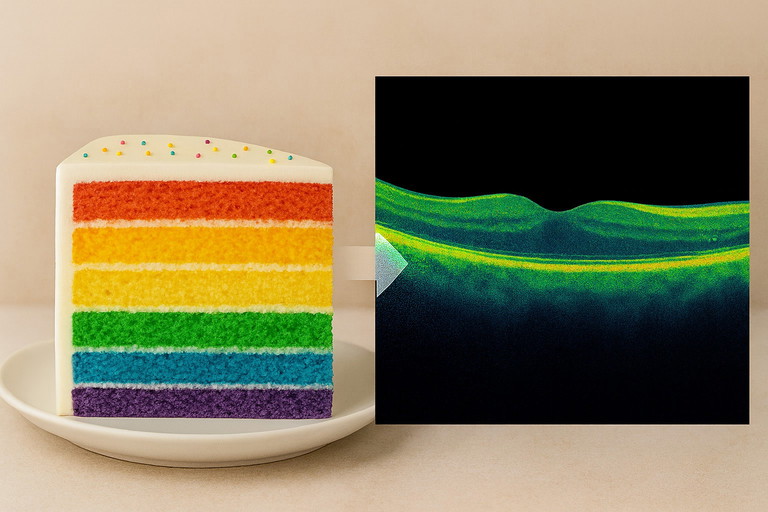

OCT transforms how patients understand their eye health. Imagine an uncut layer cake where you can’t see the cream or sponge inside. OCT is like slicing the cake to reveal every layer clearly (Figure 3). It shows the retina’s structure and any problems in fine detail.

When patients see fluid-filled cysts in diabetic macular oedema, the distorted contour of an ERM, or the gap in a macular hole on their own scan, their understanding improves. Pointing to the screen and saying, “See this wrinkled surface. That is the thin membrane we discussed, and it explains why the lines on your Amsler grid look wavy,” makes the condition tangible and acceptance of management plans more likely.

AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

The Carpet Analogy

The retina is one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body because it is constantly converting light into nerve signals for the brain. This activity produces waste products of metabolism. Over many years, some of these waste products build up beneath the retina as deposits called drusen. A helpful way to picture this is to think of the retina as a fine carpet. Drusen are like small lumps developing under the carpet. At first, the carpet still works; however, these lumps mark the earliest stage of AMD.

Once patients understand drusen, explain that AMD can develop in two distinct forms.

Geographic atrophy (dry AMD). In some areas, parts of the carpet slowly wear out, becoming threadbare, leaving permanent bare patches (Figure 4). This is a gradual process, and we cannot re-weave the carpet. This helps manage expectations about the limitations of current therapies for atrophy.

Neovascular AMD (wet AMD). In other cases, abnormal blood vessels grow beneath the carpet like leaky pipes under floorboards. When they leak, they cause water damage that lifts and stains the carpet, causing blurred vision.

To explain treatment, I use a different analogy. Think of the retina as a garden lawn. In wet AMD, abnormal blood vessels grow where they don’t belong, much like invasive weeds pushing through a lawn. These weeds damage the healthy grass and soil structure, just as the abnormal vessels leak fluid and damage the retina, impairing its function. The good news is that eye injections work like a powerful weed killer (Figure 5). They shrink these abnormal vessels and stop them from leaking, which helps the retina recover. And just as weed killer often needs to be reapplied to keep weeds from returning, regular injections are needed to keep the abnormal vessels under control.

AREDS2 Supplements in Plain Language

When discussing Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) supplements for patients with intermediate AMD, I use a sun-exposure analogy to explain cumulative oxidative damage: “Think of your retina as skin that has been exposed to the elements over a lifetime. Ultraviolet light, smoking, and other stresses slowly wear the tissue. The body also has a natural clean-up system made of proteins called the complement system. Normally, it helps remove debris, but in some people, it becomes overactive and causes low-grade inflammation that adds to the damage.

“AREDS2 supplements work like an internal sunscreen (Figure 6). They contain antioxidants that help neutralise ongoing oxidative stress. They will not reverse existing damage, but in selected patients with

Understanding this helps set realistic expectations. It also opens the door to addressing a common unspoken fear of going completely blind. I reassure patients that AMD affects central vision but does not cause total blackness. Peripheral vision remains, allowing them to continue moving around and to maintain independence.

Figure 3. OCT layer-cake analogy. The OCT scan is like a side-on slice through a cake: each band represents a different retinal layer.

Figure 4. Carpet analogy. Threadbare patches mirror areas of geographic atrophy in AMD.

Figure 5. Garden-weed analogy for neovascular AMD. Abnormal ‘weed-like’ vessels damage the retinal lawn; anti-VEGF injections act as a targeted weed killer, reducing leakage and regrowth.

Figure 6. AREDS2 sunscreen analogy. As sunscreen protects skin, AREDS2 nutrients help shield the macula from oxidative stress. intermediate AMD, can reduce the risk of further deterioration.”

EPIRETINAL MEMBRANE

The Tissue Paper Analogy

To explain an ERM, I compare the delicate retina to a sheet of tissue paper. The ERM is like a thin, fibrous layer of scar tissue that grows across the surface. As it contracts, it crumples the fragile tissue paper, distorting its smooth surface. This wrinkling explains why straight lines can appear wavy and vision becomes distorted.

As the scar tissue continues to contract, it can pull on the retina and its fine blood vessels, causing swelling that further impairs function and blurs vision.

Expectation-setting for surgery. Even after carefully peeling the ERM and smoothing the tissue paper, it will never be perfectly flat. The goal is a significant reduction in distortion and swelling, which usually improves clarity and comfort, rather than restoring vision to normal.

Macular Holes

For macular holes, I build on the tissue paper analogy and explain: “Sometimes, as the vitreous gel pulls away from the retina, it can create a tiny hole right in the centre of that delicate tissue paper. This leads to a central blind spot and distortion.

“Surgery aims to close the macular hole and allow healing. First, the vitreous gel that caused the problem is removed, so it can no longer tug on the retina. Then, fine scar tissue around the hole is gently peeled so the edges can come together, effectively closing the hole. But that is not enough on its own. The edges need support to heal, similar to a broken finger that needs a splint to hold it steady until the bone mends. At the end of surgery, a gas bubble is placed in the eye. The bubble acts like an internal splint, pressing the edges together until sealed.

“Because the bubble floats, patients need to keep their head in a position that directs it against the macula. For most people, this means staying face-down for the first few days. By looking at the floor, the bubble rises to the back of the eye and presses exactly where it is needed.”

“For diabetic patients, think of the retina as a garden and the blood vessels as its irrigation pipes”

TIMING OF SURGICAL INTERVENTIONS

The Wine Stain Analogy

Timing is critical in the management of many macular disorders. I often use a carpet and red wine analogy. “Imagine the retina as a fine carpet. If red wine is spilled and you blot it immediately, the stain is smaller and less likely to set. If it is left for weeks or months, even expert cleaning leaves a permanent mark. In the same way, earlier surgery aims to limit permanent damage and maximise recovery.”

This is particularly relevant to macular holes and epiretinal membranes. Visual outcomes relate closely to preoperative status; better acuity and shorter symptom duration before surgery are associated with better postoperative acuity. In suitable cases, earlier surgery is often associated with better final outcomes than waiting until vision declines to traditional thresholds such as 6/18.

VITREOUS CHANGES: PVD AND FLOATERS

Explaining Normal Ageing

In youth, the vitreous is a firm gel with the consistency of a soft-boiled egg. As we age, it liquefies, causing its consistency to become more like a raw egg. Eventually, it separates from the retina. This is a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). As the gel pulls on the retina, it can stimulate it, causing flashing lights, usually in dim conditions.

For floaters, a snow globe analogy resonates: “The eye is like a snow globe. As the vitreous breaks down, clumps form. Every time the eye moves, the snow swirls across vision.”

Retinal Tears and Detachment: The Wallpaper Analogy

For most people, the vitreous separates cleanly from the retina, like wallpaper peeling smoothly off a wall. In some people, a small patch of vitreous remains firmly attached at a focal adhesion on the retina, like a bit of wallpaper still stuck to the wall. When the surrounding gel detaches, that fixed attachment can tear the retina. Fluid can then pass through the tear and track beneath the retina, like water seeping under loosened wallpaper and lifting it away. When that happens, the retina peels free. This is a retinal detachment needing urgent repair. Whether we act immediately depends on the macula. If the detachment is macula-on, the central wallpaper is still attached and this is a true same-day emergency to protect central vision. If the detachment is macula-off, the central wallpaper has already lifted off. The urgency is reduced, but surgery is planned within the next week to reattach the retina and optimise recovery.

Myopia and Retinal Risk

For myopic patients, I take extra time to explain their increased retinal risks. “In myopia, your eye is longer than average, like a rugby ball instead of a soccer ball. This means the internal surface area is larger, and the retina has to stretch to cover it, like stretching a balloon as you blow it up. The more you inflate the balloon, the thinner the rubber becomes. Similarly, the more myopic you are, the thinner and more fragile your retina becomes.”

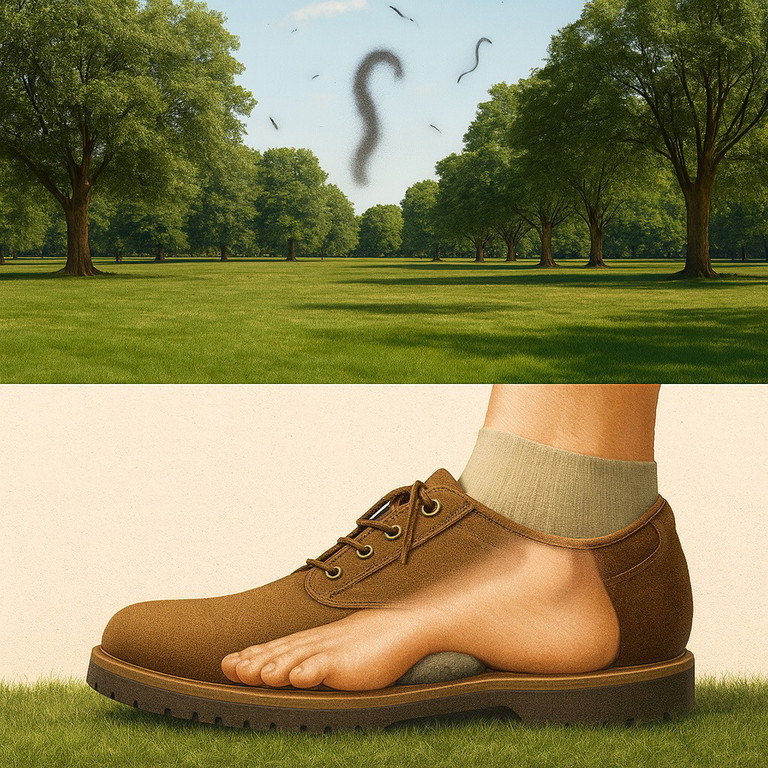

Figure 7. Floaters as a pebble in the shoe analogy. As a pebble makes a walk tolerable but unpleasant, floaters allow sight but may diminish the experience.

Figure 8. Snow-globe analogy for floaters. Vitrectomy eliminates vitreous floaters by removing the gel and replacing it with clear fluid.

This thinning makes the retina more prone to developing holes or tears, particularly during a PVD. “It’s like the difference between pulling tape off thick cardboard versus thin tissue paper. As a result, the thinner material is more likely to tear.”

Myopic patients also face the risk of myopic macular degeneration, where the central retina becomes so thin that it can develop cracks or bleeds. “The stretched, thinned macula is like overworked elastic that starts to fray and split. This can lead to bleeding under the retina or scarring that affects central vision.”

FLOATER TREATMENT CONVERSATIONS

The conversation around floater treatment has evolved. For patients with persistent floaters that significantly impact quality of life, treatment options exist.

Analogy. “Having chronic symptomatic floaters is like having a pebble in your shoe. It won’t stop you from going on a beautiful walk, but it can stop you from fully enjoying it. Similarly, floaters might not prevent you from seeing, but in some cases, they can significantly diminish your quality of life and enjoyment of visual activities,” (Figure 7). For many patients, simply validating their symptoms and acknowledging the impact on their life is the most important first step, as they have often been dismissed for years.

With that in mind, for suitable patients who are troubled by chronic floaters, there are two surgical treatment options:

YAG laser vitreolysis. For selected patients with discrete, easily visible floaters located away from the retina, a YAG laser can be used to break up large floaters into smaller pieces, like “crushing ice cubes into snow”. The goal is symptom reduction rather than complete elimination.

While not all floaters are suitable for this treatment, it can provide relief for some patients without the risks of more invasive surgery.

Vitrectomy surgery. This is the definitive treatment for extensive floaters or those unsuitable for laser. The surgery essentially replaces the murky ‘snow globe’ liquid, along with all the floaters, with clear fluid (Figure 8). The improvement in visual quality can be significant for the right patients.

It is essential to counsel patients on the tradeoffs: the risks of surgery. This includes the development of a cataract within a few years following vitrectomy.

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY: THE GARDEN UNDER STRESS

For diabetic patients, “think of the retina as a garden and the blood vessels as its irrigation pipes”.

“High blood sugar and high blood pressure damage those pipes. Early on, the pipes begin to leak and small puddles appear in the garden. Those puddles are the tiny haemorrhages and microaneurysms we see on exam. If the centre of the garden becomes waterlogged, that is macular oedema, and it causes blurred or distorted central vision.

“Anti-VEGF injections are a treatment to help seal the leaks and dry out the macula so the central garden can recover. In more advanced disease, the garden becomes starved of oxygen and starts to grow fragile, abnormal vessels, like invasive weeds, that bleed easily. Laser treatment is like pruning the outer parts of the garden, so the whole area needs less oxygen. That reduces the stimulus for abnormal vessel growth and helps protect the central, most important area.”

Finally, the whole garden depends on wider systems. “Your GP and endocrinologist control the water supply and the fertiliser. Keeping blood sugar and blood pressure under control is the single most important thing for a healthy garden.”

Key Takeaways

1. Embrace analogies. Simple comparisons like a ‘carpet’ for AMD or ‘wallpaper’ for retinal detachment transform patient understanding and reduce anxiety.

2. Show, don’t just tell. Use the patient’s own OCT scan, describing it as a ‘slice of cake’ to make pathology tangible and the treatment rationale clear.

3. Set realistic expectations. Analogies for surgery (e.g., smoothing ‘crumpled tissue paper’ for ERM) help explain that the goal is stabilisation and modest improvement, not perfection.

4. Validate floater symptoms. The ‘pebble in your shoe’ analogy acknowledges the quality-of-life impact and opens a productive conversation about management options.

5. Align your language. Co-management is strongest when the optometrist and surgeon use a consistent narrative, reinforcing patient confidence across the care pathway.

Safety-Netting Language

Explaining red flags for PVD: “Think of the wallpaper peeling off the wall. Most of the time, it comes off cleanly, but we need you to watch for signs that it might have torn the plaster. A sudden, dramatic increase in the ‘snow globe’ floaters, or a persistent, flashing strobe light in your peripheral vision, could be a warning sign of a tear. If you see a curtain or shadow appearing in your side vision and staying there, that’s an emergency, like the wallpaper starting to sag off the wall. If any of that happens, we need to hear from you straight away.”

MODERN SURGICAL PATHWAYS

Phacovitrectomy: Solving Two Problems in One Operation

For patients with both a cataract and a retinal problem, such as an ERM, macular hole, or dense floaters, a combined operation (called a phacovitrectomy), involving both cataract surgery and vitrectomy surgery performed in one operation, can make sense.

Returning to the camera analogy, “it’s like having both a scratched lens and a damaged sensor”. Fixing both in one visit means one operation, one recovery period, and one set of drops. This avoids the need to have two separate operations.

Optometrists are key in identifying patients who are suitable for phacovitrectomy surgery.

For example, a patient with 6/12 vision from a moderate cataract and a symptomatic ERM may be a good candidate for this combined approach.

BUILDING TRUST THROUGH UNDERSTANDING

Effective communication transforms retinal care. The analogies in this article are practical tools that help patients to understand complex disease, set realistic expectations, and feel confident in a shared plan. When optometrists and surgeons use consistent, clear language and share images that make the invisible visible, patients become active partners in their journey.

Dr Simon Chen MBBS FRANZCO is an experienced cataract and vitreoretinal surgeon at Vision Eye Institute, Chatswood in Sydney. With a practice dedicated to cataract and retinal surgery, particularly complex cataract surgery in eyes with retinal disease or trauma, Dr Chen has performed cataract or retinal surgery on over 100 Sydney optometrists and their closest relatives. He was the first surgeon in the world to perform femtosecond laser cataract surgery combined with vitrectomy surgery.

Dr Chen graduated in medicine and surgery from the University of London. He trained in ophthalmology at the teaching hospitals of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge (UK), followed by vitreoretinal surgery fellowships at the Oxford Eye Hospital and Lions Eye Institute, Australia. He has published on various aspects of cataract and retinal surgery. He has been a principal investigator for numerous international clinical trials of novel treatments for retinal disease. Dr Chen is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales.

To earn your CPD hours from this article, visit: mieducation.com/practical-analogies-for-patient-friendly-conversations-during-retinal-consultations.