mieducation

Co-managing Cataract Patients Red Flags for the First 30 Days

Cataract is the leading cause of visual impairment worldwide, accounting for 65.2 million cases of impairment and blindness globally.1 With ageing populations in all western countries, these numbers are projected to increase substantially. Hence, the management of the cataract patient remains a major public health concern.

Cataract surgery is deemed to be safe and predictable, particularly when performed by an experienced surgeon. There are, however, challenges that can arise in the immediate post-operative period that relate to specific patient characteristics (general health issues). There are also specific ocular characteristics that can determine whether a patient has a smooth recovery in the first 30 days after routine surgery.

WRITER Dr Alex Ioannidis

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD activity, participants should be able to:

1. Realise the characteristics of patients at greatest risk of complications post-cataract surgery,

2. Be aware of complications that can present post-cataract surgery,

3. Be aware of the comorbidities that can increase risk for cataract patients, and

4. Understand when to refer a patient back to their surgeon.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS AND COMORBIDITIES

Our patients present in all shapes and sizes, but some patients have added health issues that can complicate the post-operative course of recovery. One major problem that we all face is the waiting time for surgery. This is unfortunately more of an issue for patients on public waiting lists, where patients with significant health issues can deteriorate from the point of view of their general health while waiting for cataract surgery.

For example, patients with mild cognitive impairment can progress to develop more severe cognitive impairment and become unsuitable for local anaesthesia surgery, requiring a general anaesthetic instead. Patients with progressive cardiac disease or lung disease may also find it impossible to lie flat due to breathlessness. In some cases, these patients cannot have surgery at all as they may become medically unfit.

Patients with diabetes may also develop progressive retinopathy requiring antiVEGF therapy, but also proliferative diabetic retinopathy requiring vitrectomy or retinal laser at the time of their cataract surgery or prior.

OCULAR CHARACTERISTICS

Patients with certain diseases of the anterior and posterior segment may require more careful attention in the immediate postoperative period.

For example, patients with glaucoma require careful monitoring of the intraocular pressure (IOP) in the post-operative period, especially on day one and week one after surgery. It is not uncommon for these patients to have labile IOP control and they may require an adjustment to their IOP medication regimen, sometimes even with oral supplementation with acetazolamide (Diamox) for the first few days after surgery. This is particularly true of patients with pseudoexfoliation or pigment dispersion, who often get significant IOP spikes soon after surgery.

Patients with corneal transplants also need to be watched carefully after cataract surgery. This is to monitor IOP but also to look out for evidence of graft failure or corneal decompensation, and adjustments made to the steroid regimen after cataract surgery.

Patients with diabetes and those with known macular disease, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), are more prone to develop macular oedema and need to be watched carefully. It is not uncommon to cover patients with anti-VEGF therapy at the time of the cataract surgery to prevent AMD progression in the post-operative period.

PSYCHOLOGY OF THE POST-OPERATIVE PATIENT

One aspect that is often overlooked is the psychology of the post-operative patient after cataract surgery. Some patients are genuinely terrified of having eye surgery and, despite what we say to allay their fears, still face the prospect of ocular surgery with significant trepidation. Studies have shown that distress levels in some patients with an ocular condition are as high as having been given a diagnosis of melanoma, acquired immunodeficiency, and bone marrow transplantation.2

It is, therefore, understandable why some patients will report back to the optometrist or ophthalmologist within days of routine surgery with typically minor ailments such as a localised subconjunctival haemorrhage or a gritty eye. However, what is typical to us, as health care specialists, appears as a major complication to the patient.

In a study conducted at Moorfields Eye Hospital, 30% of attendances to a dedicated eye casualty were deemed as non-urgent, yet patients reported “great concern” as a reason for attending the casualty department.3

Hence, most patients will report minor ailments in the first few days of surgery, such as a gritty eye, or a subconjunctival bleed, which relate to sensory changes on the ocular surface. Some patients report optical/ refractive phenomena such as fluctuating vision, glare (needing to use sunglasses indoors), and transient dysphotopsias. In all cases it is important to reassure the patient that things will settle in time and to continue their drop regimen.

Figure 1a. Acute hyaluronidase (Hyalase) allergy in a patient after routine cataract surgery. Note the lid swelling on the right, three days after cataract surgery.

Figure 1b. One week later, the patient made full recovery with 6/6 vision after taking prednisolone 25 mg for seven days.

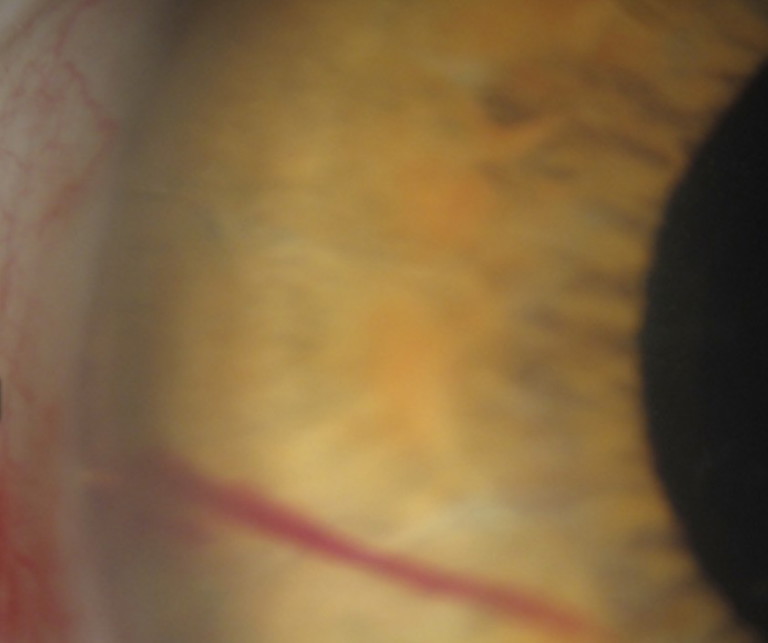

Figure 3. A herpetic dendrite in a patient soon after cataract surgery. This patient presented three weeks post-surgery and was treated with topical acyclovir ointment for seven days, achieving complete resolution.

TYPICAL RED FLAGS AFTER SURGERY

Any patient presenting with loss of vision needs to be fully evaluated in the immediate post-operative period.

Loss of vision that is painless may indicate a vascular event, which may be ocular (arterial or vein occlusion) but also could have a central cause, such as a stroke or giant cell arteritis (GCA). Painless loss of vision may also be due to macular pathology (macular oedema) or a retinal detachment. A rare cause of acute painless loss of vision after routine cataract surgery is paracentral acute middle maculopathy (PAMM). This condition was first described in 2013, and it is thought to arise though an increase in IOP after surgery, perhaps related to the anaesthetic or pressure from the eye pad after surgery, resulting in localised ischemia in the macular area.4

When patients present with painful loss of vision you need to exclude an inflammatory or infective process such as uveitis, allergic reaction or endophthalmitis.

One particular condition that needs to be mentioned is acute hyaluronidase (Hyalase) allergy. Hyalase is an agent used by anaesthetists to facilitate block diffusion in the orbit. An acute allergy can occur, typically after a second eye surgery, whereby the patient develops hypersensitivity after the first eye has been operated on.5 The patient can present after the second eye has been done with a severe allergic reaction, characterised by lid and/or facial swelling and loss of vision, within 48 hours after routine cataract surgery (Figure 1a). In this setting, it is important to exclude acute endophthalmitis. Typically, patients with acute hyaluronidase allergy respond favourably if oral steroids are introduced early on presentation (Figure 1b).

PAIN AFTER CATARACT SURGERY

Severe pain after cataract surgery is rare. However, pain is a very subjective sensation, and some patients will report more pain than others. Some sources of pain include the light of the microscope during the procedure, the type of anaesthetic block used to numb the eye, and – very importantly – the psychosocial make-up of the patient.

A comparative study between topical versus sub-tenons anaesthesia, using a standardised light source, found that the topical group reported more light sensitivity as compared with the sub-tenon group, indicating that the latter achieves better anaesthesia and a more comfortable experience for the patient.6

Very anxious patients are more likely to report pain than the stoical ones. Other factors include the grade of the cataract (density), whether there are other ocular co-morbidities such as pre-existing dry eye, glaucoma, or disturbances of the conjunctiva, such as a pterygium and surface scarring (keratitis, Salzmann degeneration).

Patients that have had other types of surgery such as trabeculectomy, glaucoma devices (tubes), corneal grafting, and vitrectomy, may report more pain as there may be scarring of the conjunctiva and sclera. It is important to consider bleb failure and corneal graft rejection in these patients (Figure 2). In general, however, these patients tend to respond well with a slow taper of steroids and the use of topical lubricants after cataract surgery.

MANAGING INFLAMMATION AFTER CATARACT SURGERY

Inflammation in the immediate postoperative period is usually well controlled with topical steroids and in most cases a twoto three-week course of prednisolone acetate/ phenylephrine hydrochloride (Prednefrin Forte) or dexamethasone (Maxidex) is enough to supress the inflammatory drive after routine surgery.

In cases where the cataract is very dense, a fair amount of energy will be required to break up the lens so we expect to see more inflammation in the anterior chamber (cells and flare) and this may be accompanied by corneal oedema. It is not unusual for patients to have acuities of counting fingers or 6/60 for the first few days or week. As the inflammation settles the vision can improve to 6/6 within that short period of time. Hence it is important to offer reassurance to the patient that things should settle in time.

There are cases, however, where inflammation can be protracted. These include patients with a history of previous eye surgery and or diabetes.

Uveitic patients may also have a flare up of their uveitis and in some cases a short course of oral steroids is prescribed for four to seven days prior to cataract surgery.

Patients with known corneal disease – for example, those with corneal grafts or Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED) may have significant post-operative inflammation and corneal oedema that may require several weeks of topical steroid use. In some cases of FED, the corneal oedema does not resolve, and patients may need an endothelial graft such as Descemets’ stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSEAK) or Descemets’ membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) to restore corneal clarity.

The Gritty Eye After Cataract Surgery

Pre-existing Conditions

• Blepharitis/OSD

• Sicca syndrome

• Ocular rosacea

• Glaucoma

• Pseudoexfoliation

• Keratitis/Salzmann degeneration

• Surface scarring

• GVHD

Iatrogenic Conditions

• Corneal wounds – surgery

• Healing response

• Topical drops – multiple

• Injected bleb – RED FLAG

• Hazy graft – RED FLAG

• Sutures – buried/exposed

• Old scarring/pterygium/tubes

• Subconjunctival bleed

“… most patients will report minor ailments in the first few days of surgery, such as a gritty eye, or a subconjunctival bleed, which relate to sensory changes on the ocular surface”

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) reactivation can also occur in patients with a history of herpetic eye disease and for this reason we often prescribe oral acyclovir or valacyclovir (Valtrex) in the post-operative period as surgery and topical steroids can act as triggers for HSV re-activation (Figure 3).

Finally, patients who have had some degree of iris manipulation tend to develop an inflammatory reaction. This may include the use of iris retractors (iris hooks) or the malyugin ring to dilate small pupils at the time of cataract surgery.

It is important to mention that one must always consider the possibility of acute postoperative endophthalmitis in any patient that presents with intraocular inflammation after cataract surgery. The important signs are pain with loss of vision, anterior chamber cells and/or hypopyon, vitritis, and some degree of periocular swelling. If in doubt, it is best to seek a second opinion on the same day of presentation and discuss with the ophthalmologist or refer to eye casualty immediately for a diagnostic tap and injection of intravitreal antibiotics.

MANAGING IOP AFTER CATARACT SURGERY

In most routine cases it is unlikely that we will see an IOP spike after routine cataract surgery. The most common cause of an IOP spike is retained viscoelastic behind the IOL implant. This viscoelastic tends to migrate into the anterior chamber and cause poor outflow at the level of the trabecular meshwork, resulting in a transient IOP spike.

This typically occurs three to seven hours after surgery when the patient has typically gone home from the day surgery.7

In a comparative study, patients undergoing cataract surgery by residents ( junior surgeons) had a two to fivefold high rate of IOP spikes than patients whose surgery was performed by senior surgeons. Apart from failing to detect retained viscoelastics, there were a number of significant variables in this study, including vitreous loss at surgery, prior ocular trauma, pre-existing glaucoma, glaucoma suspect status, and male sex.8 This underlines the importance of checking the IOP in high risk cases after surgery; a good learning experience for the junior surgeons that are keen to master their skills. Other conditions where the IOP can be elevated include pseudoexfoliation, patients with floppy iris syndrome due to use of tamsulosin (Flomax), and patients with pre-existing uveitis.

The management of IOP spikes depends on the presentation. In cases where the IOP is very high – over 40 mmHg – an anterior chamber paracentesis is required to lower the IOP and offer immediate relief to the patient. This needs to be followed with appropriate medical cover, either with oral acetazolamide or topical medications, to keep the IOP low until the next review.9 In cases where the IOP is lower, patients do well with medical therapy and do not require a paracentesis. It is important, however, to check the IOP within a week after surgery as the IOP may rise again.

Glaucoma patients are a particular cohort of patients that require careful IOP monitoring after cataract surgery as they invariably have some degree of optic nerve damage. Regardless of whether they have had cataract surgery alone, or in combination with a minimally invasive glaucoma device (MIGS), they require a day one check-up of the IOP. Again, depending on the level of optic nerve damage and visual field (VF) loss, the IOP needs to be monitored closely in the post-operative period to prevent further glaucomatous damage, resulting in further VF loss. Additional medications may be needed in cases where the IOP is considered too high for the given patient.

RETAINED LENS FRAGMENTS

The incidence of retained lens fragments in the anterior chamber ranges from 0.1% to 1.5%.10 This complication may lead to significant patient morbidity including decreased visual acuity, corneal oedema, glaucoma, retinal detachment, and cystoid macular oedema. In addition, fragment retention may require surgical intervention with an anterior chamber washout as symptoms are frequently refractory to standard medical management.

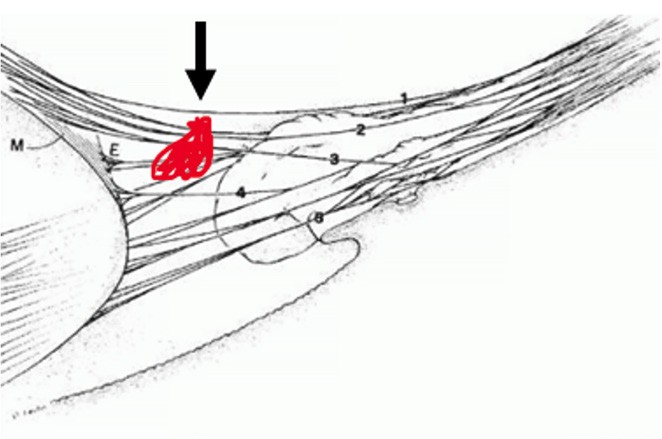

The reason lens fragments get retained is simple. During the breakup of the cataract (nucleofractis) small fragments fly off in all directions inside the eye and get lodged behind the iris, often within the annulus of Zinn, which acts like a spider’s web (Figures 4 and 5). The fragments are eventually released back into the anterior chamber, often days after the operation has been completed.

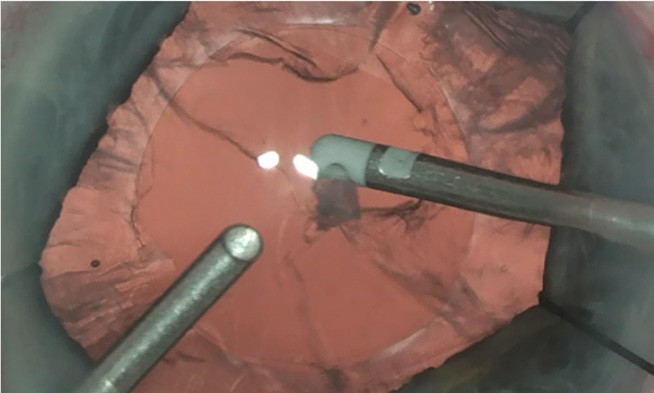

Figure 4. Small fragment held at the tip of the aspiration cannula. Small fragments can fly off in all directions and hide behind the iris plane.

Figure 5. Small retained fragment within the zonule (annulus of Zinn) the zonule can act as a web that traps the small fragment behind the iris.

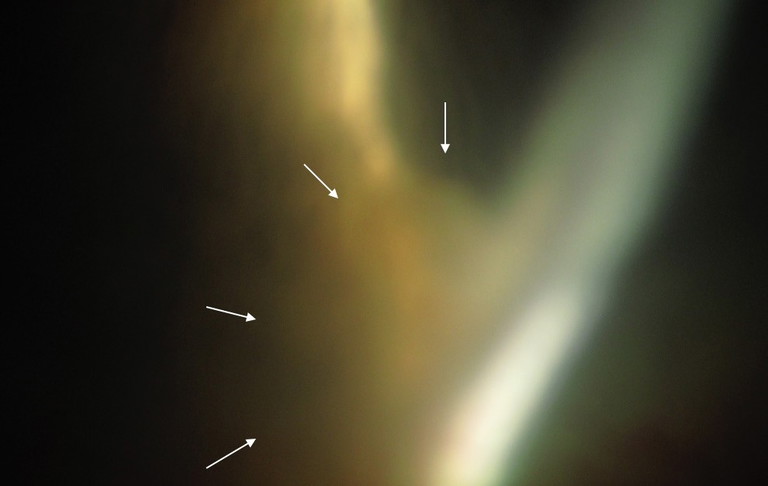

Figure 6. Small fragment in the angle (arrows). This patient had this fragment in the angle for five years after cataract surgery. He presented with a history of grittiness and foreign body sensation. AC washout was performed, and the issue was resolved.

The decision to take a patient back to theatre for a washout depends on the size of the retained fragment. Most fragments that are small (<2 mm) dissolve on their own over a period of four to six weeks, but patients need regular reviews, as they may get an inflammatory response (post-op uveitis) and IOP control issues (secondary glaucoma). Larger fragments (>2 mm) should be referred back to the surgeon for an AC washout.

Most cases of retained lens fragments are identified post-op day one, some at the week one visit, and in some cases, the timeline for identification is variable, with some reports of identification and diagnosis years later.11

I have personally seen a patient that presented to eye casualty with a retained lens fragment that was present in the eye for five years (Figure 6).

Figure 7. A case of retained Chlorsig ointment (arrow) in a 98-year-old man that rubbed his eye vigorously two days after cataract surgery. The patient was taken back to theatre to have this removed.

Figure 8. An example of iris prolapse after trauma. Note the peaked pupil sign (white arrow) and the prolapsed iris tissue (black arrow) through the wound. This is a medical emergency that requires prompt return to theatre to reposition the iris into the AC.

Figure 9. A transient hyphaema in a patient after microstent implantation into the angle. This patient presented on day one after surgery. The pressure was normal and when the patient was seen a week later, the hyphaema had cleared completely.

OTHER RETAINED FOREIGN OBJECTS

Although unusual, it is not uncommon to discover various retained foreign objects in the anterior chamber after routine cataract surgery. Such objects include metallic fragments from the phacoemulsification hand piece that flake off and are deposited on the iris or the angle. The most common are plastic or cotton microfibres from the draping materials used. These are typically inert and, if small, can be left alone as they are unlikely to cause an inflammatory reaction in the anterior chamber.12 On one occasion, a patient presented with a quantity of Chlorsig (chloramphenicol) ointment floating in the superior angle that required an anterior chamber washout to prevent a secondary complication (Figure 7).

UNUSUAL PUPILS AFTER CATARACT SURGERY

Even though patients can have an uneventful experience when undergoing cataract surgery, one must consider that complete wound healing does not take place immediately. Other complications can arise, especially after inadvertent trauma to the eye resulting in changes to the iris/pupil.

Case Study

A 54-year-old man presented to eye casualty one week after routine cataract surgery, complaining of blurred vision and watering sensation in the operated eye. He reported that earlier in the day he fell in the garden and bumped his eye on the edge of a garden chair.

His vision was 6/24, no improvement in pinhole, and the IOP was 4 mmHg. He had a peaked pupil, along the main wound, and he was Seidel positive with a fluorescein strip test.

A diagnosis was made of prolapsed iris, and he was taken to theatre for iris repositioning and suturing of the main cataract wound (Figure 8).

Although iris prolapse has been reported as early as the 1950s, it has resurfaced in the literature recently due to the use of alpha–1 antagonists used to treat prostatic hyperplasia that can make the iris ‘floppy’ and difficult to manage during surgery.13 The use of agents such as tamsulosin (Flomax) produce a syndrome where the iris is ‘floppy’, dilates poorly, and has a tendency to prolapse through the wounds during cataract surgery. This is recognised as intra-operative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). In a large cohort of patients, 57% of patients taking tamsulosin experienced features of IFIS versus 1% in the non-tamsulosin group.14

It is, therefore, important to recognise the peaked pupil sign in a post-operative patient and refer back to the operating surgeon or to eye casualty to prevent infection (endophthalmitis) and or iris necrosis.

BLEEDING IN THE EYE

Blood in the anterior chamber (hyphaema) is uncommon after routine cataract surgery. There are, however, some cases that will present with blood cells circulating or a layer of blood in the inferior angle. Rare causes include iris margin microhaemangiomas (Cobb’s tuft), which can bleed spontaneously, and Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis; the latter presenting with blood in the angle after cataract surgery (Amsler sign).

More recently, the advent of microstents to treat glaucoma at the same time as cataract surgery can result in a transient hyphaema that settles within a few days after surgery (Figure 9).

Microhyphaemas in this setting do not require special management as most are transient and the patient is already on topical steroids. It is reasonable to check the IOP as in some cases a transient IOP spike can occur, and the patient may require additional medical therapy until the hyphaema clears.

FINAL REMARKS

There is no doubt that cataract surgery in the modern era is an exceedingly safe procedure and this is highlighted by the fact that, in experienced hands, complications are exceedingly rare.

Nevertheless, it is important to be aware that on occasions, a co-managing optometrist is likely to encounter an unusual case after surgery and this article has highlighted the likely rare presentations and when to refer to the operating surgeon or the local eye casualty for further management.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit: mieducation.com/co-managing-cataract-patientsred-flags-for-the-first-30-days.

References available at mivision.com.au

Dr Alex Ioannidis MBBS FRCOphth FRANZCO is an ophthalmic surgeon with over 20 years of experience performing small incision refractive cataract surgery. He practises at the Vision Eye Institute, Retina Specialists Victoria, and Mornington Specialist Eye Clinic, where he also offers tailored surgical solutions for his patients with conditions of the anterior segment.

Dr Ioannidis has held an Honorary Clinical Lecturer position at the University of Melbourne since 2014 and is involved in registrar training at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. As an expert in his field, he has published extensively and has been the recipient of several awards for his research and academic achievements.