mistory

A Closer Look

Bioptic Telescopes & Fitness to Drive

WRITERS Associate Professor Meri Vukicevic, Associate Professor Rwth Stuckey OAM, Dr Pamela Ross, and Adjunct Professor Wendy Macdonald

When it comes to determining who is fit to drive, adequate vision is a nonnegotiable requirement for road safety. What about people who don’t meet all of the standard vision requirements but still want, or feel they need, to drive? Might using a bioptic telescope enable them to drive safely?

Bioptic telescopes (BTs) are devices that can be used in a variety of situations to compensate for reduced visual acuity. They have been hailed in parts of the world, particularly the United States, as an assistive technology that can enable driving by people with low visual acuity but sufficient visual fields. BT use is permitted in most states of the US, although with highly variable licence conditions that commonly exclude driving at night.

BTs are miniature telescopes, usually mounted on the upper part of the person’s normal glasses (Figure 1). The current Austroads guidelines on Assessing Fitness to Drive, describe BTs as:

“used momentarily and intermittently when driving, the majority of which occurs at the corrected visual acuity provided by the person’s glasses. The person drops their chin slightly to view through the telescope for magnification, then lifts their chin to view through their standard corrective lens.”1

Use of a BT can enable drivers to read the information on road signs at much greater distances, as shown in Figure 2.

IS BT USE BY DRIVERS PERMITTED IN AUSTRALIA?

Australian driver licensing authorities may consider “information from an assessment performed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist” when deciding whether to permit a private vehicle driver to use a BT.1 Use by commercial vehicle drivers is never permitted.

To date, a small number of drivers who do not meet current fitness-to-drive standards have been conditionally licensed to use a BT.

Figure 1. Bioptic mounted into the person’s carrier lenses (image used with permission from Ocutech, Inc.).

Groups such as Bioptic Drivers Australia (biopticdriversaus.com) are advocating for a dedicated standard within the national Assessing Fitness to Drive guidelines urging policymakers to formalise bioptic driving.

MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE

Vision is not the only factor relevant to driver licensing. The key question in any fitness-todrive assessment is whether a person can “act or react to the driving environment in a safe, consistent and timely manner”, and at present “there is insufficient information from human factors and safety research of drivers using these devices” to answer this question.1

Figure 2. Highway sign using 3x Galilean Bioptic (image used with permission from Ocutech, Inc.).

To address this information gap, Victoria’s Department of Transport and Planning commissioned a multidisciplinary research team from La Trobe University to conduct a rigorous, independent analysis of the safety implications of BT use by Australian drivers.

The results may challenge some assumptions held by clinicians, advocates, and policymakers alike.

THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The La Trobe University research team used a Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE) conceptual framework to examine how BT use might affect a driver’s capacity to cope safely with the multiple demands of real-world driving. More specifically, the following two questions were investigated:

1. Which factors affect driving performance and should be taken into account when considering use of a BT by Australian drivers?

2. How would use of BTs be likely to affect driver performance and road safety in Australian road and traffic environments?

Addressing the first question, the researchers formulated a hierarchical taxonomy of the main factors that affect safe driving. The taxonomy reflects key elements of the complex road-traffic system within which drivers operate, with a focus on safety-related factors likely to be affected by a driver’s use of a BT.

To address the second question, the research team utilised two methods.

First, it undertook a systematic review of existing research on drivers’ use of BTs. Key content from research articles identified by the systematic review was extracted and mapped against the taxonomy of factors that affect driver performance and safety. Organising evidence in this way enabled evaluation of how much is currently known about each of the taxonomy factors. Evidence was then further synthesised and reported using the taxonomy’s framework.

Second, HFE analyses of a diverse set of driving task scenarios were conducted, each of which was specified to represent an existing road location and associated traffic situation in Melbourne or rural Victoria. ‘Cognitive walkthroughs’ of each scenario were then used to assess the practicability, risks, and benefits of BT use in each one.

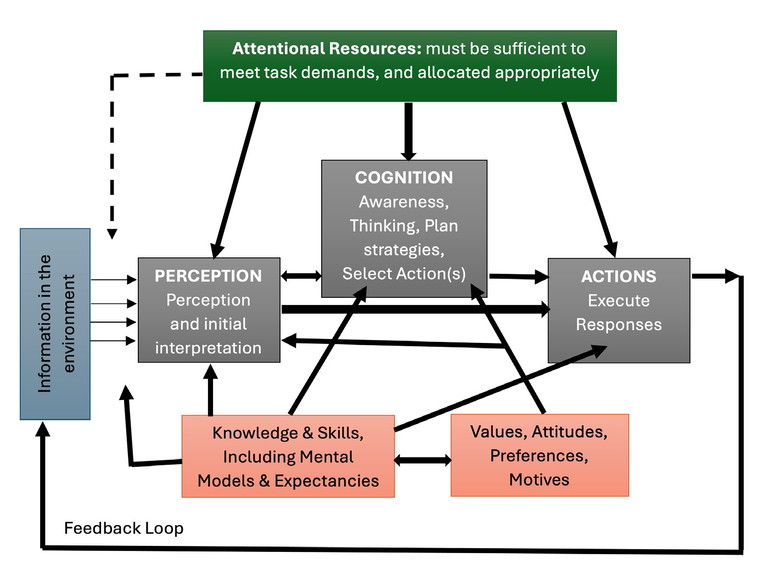

Figure 3. Attentional resources are important as drivers process information.2

FACTORS AFFECTING DRIVING PERFORMANCE

The HFE taxonomy developed by the research team included factors ranging from a driver’s visual and cognitive abilities to vehicle characteristics, the road-traffic environment, and driving-related policy and associated practice issues. The following factors were at the top level of this taxonomy:

The driver: e.g., demographics, driving experience, visual, perceptual/cognitive and other skills and abilities, driving-related attitudes/motives,

Bioptic telescope: e.g., telescope type, magnification and field of view,

Vehicle: e.g., make/model, level of automation, familiarity to driver,

Driving environment: e.g., road configuration and lane widths, speed limits, traffic conditions, presence of pedestrian and other non-vehicle road users, weather and lighting conditions, roadside characteristics (built environment, vegetation, sight distances, visual distractions, etc.),

Driving tasks requirements: ongoing tasks include maintenance of situation awareness, maintenance of safe distances from other road users or fixed objects, navigation; specific manoeuvres include gap selection, intersection negotiation, merging, overtaking, etc.

Wider system factors: e.g., driver licensing requirements, community perceptions and attitudes related to road safety, BT use by drivers, and ‘human rights’ issues, and

“ The results may challenge some assumptions held by clinicians, advocates, and policymakers alike ”

System outcomes: e.g., road crashes and associated costs, satisfaction of community mobility needs, driver licensing systems costs, public health system costs, personal wellbeing and health of drivers with low vision.

Drivers are required to notice and respond to events on the road, ahead and around them. As shown in Figure 3, this entails perception and processing of relevant information; importantly, the rate at which humans can process information is very limited. When information processing demands of the driving task are too high for a driver’s limited attentional resources, driving performance deteriorates and risk increases.

The normal, ongoing demands of driving are increased by use of a BT, because drivers need to align the telescope to a target area that is moving relative to themselves, interpret magnified information (with part of their normal visual field occluded by the magnified BT image), and then readjust back to the normal view looking through their ordinary glasses.

“ On balance, it appears likely that drivers using BTs in the US present a higher risk than age-and gender-matched peers, but a lower risk than young novice drivers ”

MAJOR GAPS IN PUBLISHED EVIDENCE

The systematic review examined 62 peer-reviewed articles related to BT use by drivers, covering a period of 50 years. Content synthesis was limited by the highly variable approaches used in these articles and their generally poor methodological quality. Most authors were experts in vision sciences and/ or clinical practitioners in that field; few if any appeared to have expertise in psychology and HFE as applied to driving and road safety. Consistent with this, mapping of evidence onto the HFE taxonomy identified many large gaps in evidence.

Very little detailed information was reported about driver characteristics apart from vision. Visual information was largely confined to clinical diagnostic categories and visual acuity as normally measured by clinicians. There was relatively little coverage of visual abilities known to be more closely linked to drivers’ crash risk (e.g., motion perception, dynamic visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and glare sensitivity).

The evidence reviewed took little if any account of how BT use affects drivers’ perceptual/cognitive performance. This is problematic because a driver’s useful field of view (UFOV) is strongly influenced by available attentional resources, and availability of these resources is strongly linked to the quality of driving performance. UFOV is more strongly related to crash risk than are measures of visual acuity.

Just as importantly, none of the published research investigated effects of varying road environments and associated driving task demands on driving performance and safety when using a BT. The impact on crash risk of these factors is well documented, and their ‘real-world’ importance was evident from self-reports of many BT users that they routinely avoid particular types of driving tasks and environments.

BTs were reported to enhance the personal mobility and quality of life of drivers who use them, but no evidence was found that their use is likely to maintain or enhance road safety. Research on how BT use affects drivers’ performance under normal driving conditions is almost entirely lacking, and research on the crash risk of drivers using BTs was very patchy. On balance, it appears likely that drivers using BTs in the US present a higher risk than age-and gender-matched peers, but a lower risk than young novice drivers.

On that basis, some argued that their crash risk is within the normally accepted range. However, much the same appears to be true of the crash risk of drivers with poor visual acuity who do not use BTs, which casts doubt on the value of BTs when driving.

ANALYSES OF REAL-WORLD DRIVING SCENARIOS

To bridge the gap between clinical vision measures and real-world driving, the research team used the ‘cognitive walkthrough’ method to analyse 19 very different driving task scenarios – from rural highways to busy suburban intersections.

Each scenario was assessed for:

• Nature and level of demands on a driver’s visual perception and information processing capacities, and the additional demands of using a BT in that scenario,

• The practicability of using a BT in that scenario, and

• The potential risks and any likely safety benefits of using a BT in that scenario.

The results were very clear: use of a BT to see a small part of the environment more clearly for a second or so does not necessarily result in safer driving.

BT use was sometimes found to be safely practicable in scenarios involving low speeds and predictable environments, such as using it to read a distant traffic sign on a quiet rural road. But in many more common scenarios BT use was either impractical because the driver’s information processing capacity would be grossly overloaded, and/ or it would cause unacceptable risk due to its negative impact on the driver’s ability to detect likely hazards.

“ BTs were reported to enhance the personal mobility and quality of life of drivers who use them, but no evidence was found that their use is likely to maintain or enhance road safety ”

Even for tasks where BT use was assessed as safe, potential road safety benefits were often doubtful. BTs are often reported as helpful in reading street signs, but many critical signs (e.g., Stop, Give Way) are designed to be easily recognised without good acuity. In unfamiliar areas, navigation apps with spoken/audio instructions may offer a safer alternative. Recent Australian research, in which participants with sub-standard acuity travelled as front-seat passengers, found that on trials where they were encouraged to use a BT when it would be helpful, they did not report higher percentages of hazards or road signs, although they reported signs at greater distances from them.

IS BT USE SAFE FOR DRIVERS?

The study found no reliable evidence that BTs reduce crash risk among drivers with low visual acuity. To the contrary – in many driving situations the extra cognitive workload and reduced field of view while using a BT could increase risk, particularly in complex or fast-paced environments. Such increases in risk were assessed as likely to outweigh any safety benefits gained from earlier reading of some traffic signs.

The La Trobe University studies referenced in this article are awaiting formal publication at the time of print.

• Stuckey R, Macdonald W, Ross P, Vukicevic M. Driving with a Bioptic Telescope: a systematic review using a human factors / ergonomics (HFE) taxonomy. 2025 [manuscript in preparation].

• Macdonald W, Ross P, Vukicevic M, Stuckey, R. Drivers’ use of bioptic telescopes: Human factors task analyses and driving risk assessments. 2025 [manuscript in preparation].

Associate Professor Meri Vukicevic BOrth PGDipl PhD is an academic and researcher in the Discipline of Orthoptics at La Trobe University.

Associate Professor Rwth Stuckey OAM BAppSc (OccTher) GradDipErgonomics MPH (OHS) PhD is an academic and researcher at the Centre for Ergonomics and Human Factors, La Trobe University.

Dr Pamela Ross BAppSci (OT) PhD is Consultant Occupational Therapist Driver Assessor, La Trobe University.

Adjunct Professor Wendy Macdonald BSc (Psych) PGDipPsych PhD is a researcher at the Centre for Ergonomics and Human Factors, La Trobe University.

References

1. Austroads, Assessing fitness to drive, 2022:207. Available at: austroads.gov.au/drivers-and-vehicles/assessing-fitnes-sto-drive, [accessed Sept 2025]. 2. Adapted from Macdonald WA, Harrison WA, Construct validity of Victoria’s new licence test, paper presented at Australasian Road Safety Research Policing Education Conference, 2008, Adelaide South Australia. Based on Wickens CD, Hollands JG. Engineering Psychology and Human Performance, Prentice Hall, 2000.