mi patient

Autoimmune Disease:

Ocular Manifestations to Watch For

WRITER Dr Margaret Lam

Autoimmune diseases frequently involve the eye, sometimes as the first sign of systemic illness. Dr Margaret Lam highlights diagnostic red flags to be mindful of in your practice.

Autoimmune conditions can present with varied ocular manifestations – from dry eye to sight-threatening orbital and intraocular disease. Early recognition, appropriate imaging/testing, and close collaboration with rheumatology and neurology are essential to preserve vision and improve systemic outcomes.

DISEASES TO WATCH FOR

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome is a leading cause of aqueous-deficient dry eye.1 Lacrimal gland lymphocytic infiltration causes keratoconjunctivitis sicca with punctate epithelial disease, filamentary keratitis, and recurrent epithelial breakdown.2 The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop (TFOS DEWS) II report framed ocular-surface inflammation and neurosensory dysfunction as central mechanisms, and supported a stepwise approach from lubricants and topical anti-inflammatories to autologous serum or scleral lenses for severe cases.1,3

Sjögren’s syndrome is a common autoimmune disease; approximately one in 10 patients with clinically significant aqueous-deficient dry eye will have underlying Sjögren’s syndrome.4 Widespread underappreciation of Sjögren’s syndrome leads to significant underdiagnosis and delays in diagnosis. The autoimmune consequences of Sjogren’s not being detected in time for treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.4

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can manifest with various ocular conditions, including the often benign episcleritis, and more severe vision-threatening conditions such as necrotising anterior scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK).

While we are all familiar with dry eye being the most common RA-related eye issue, scleritis is a serious complication characterised by pain and scleral inflammation. PUK involves corneal inflammation and ulceration that can lead to vision loss from corneal melt and perforation.5 Clinicians should be aware of the risk of systemic vasculitis that requires urgent systemic immunosuppression. Even more common, ocular surface dryness in RA contributes to increased infection risk.6

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

About one-third of patients suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have ocular manifestations, the most common being keratoconjunctivitis sicca.7 SLE can affect the retina (cotton-wool spots, retinal vasculitis/occlusion), choroid, and optic nerve. Ocular signs can parallel systemic activity and be vision threatening. Multimodal imaging (optical coherence tomography (OCT), fluorescein angiography) is essential when visual symptoms or systemic flares occur.8

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and Systemic Vasculitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) commonly affects the orbit and adnexa (orbital mass, proptosis), conjunctiva, and sclera. It can cause compressive optic neuropathy or intraocular vaso-occlusive disease. Biopsy and prompt systemic therapy are often required.9

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

Ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (ocular cicatricial pemphigoid) produces progressive conjunctival scarring with fornix foreshortening, symblepharon, entropion, and keratinisation. Early recognition and systemic immunosuppression can prevent corneal failure and blindness.10

Thyroid Eye Disease

In thyroid eye disease (Graves’ orbitopathy), inflammation with muscle and fat expansion causes eyelid retraction, proptosis, and exposure keratopathy. In moderate-to-severe active disease, systemic immunomodulatory agents are increasingly used.11

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis – granulomatous uveitis, conjunctival nodules, and adnexal disease – may present with anterior, intermediate, or posterior panuveitis; conjunctival granulomas; vitreous opacities; and optic neuropathy. Ocular disease may precede systemic diagnosis; it is important to follow the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) criteria with referrals on for chest imaging and appropriate biopsies.12,13

“approximately one in 10 patients with clinically significant aqueous-deficient dry eye will have underlying Sjögren’s syndrome”

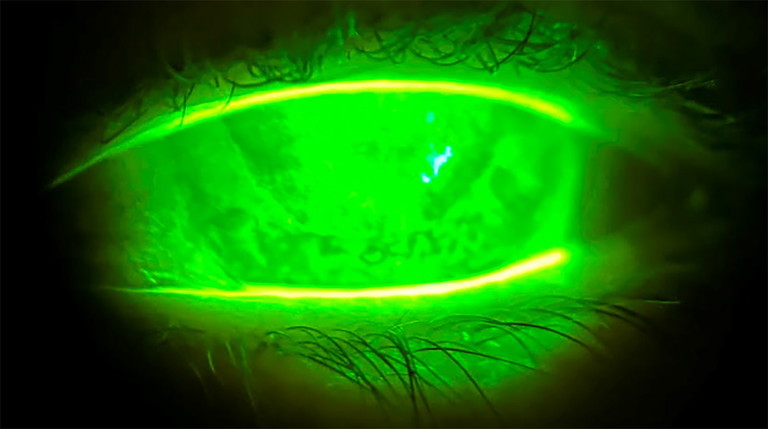

Figure 1. Ms Cahill’s left eye with severe corneal staining and keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Figure 2. Ms Cahill’s right eye with full corneal leukoma.

Figure 3. Ms Cahill’s right eye, fitted with a Capricornia Eycon custom hand-painted, coloured contact lens.

Demyelinating Diseases

Demyelinating diseases include multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD).

Acute optic neuritis (subacute painful visual loss with dyschromatopsia) is a hallmark presentation. NMOSD and MOGAD are rare autoimmune disorders where the body’s immune system attacks the myelin sheath.

Distinguishing MS-related optic neuritis from NMOSD and/or MOAD is crucial since prognosis and long-term therapy differ.14,15

MEDICATION-RELATED OCULAR RISKS

Hydroxychloroquine carries a dose- and duration-related risk of retinopathy; the American Academy of Optometry guidelines recommend baseline evaluation and structural/functional screening (OCT, visual fields, fundus autofluorescence) with surveillance for patients annually and after five years on this medication. Systemic corticosteroids raise intraocular pressure and cataract risk, making it important to coordinate monitoring with prescribers.16,17

“Early recognition and systemic immunosuppression can prevent corneal failure and blindness”

CASE STUDY FOR OPTOMETRY AND OPHTHALMOLOGY CO-MANAGEMENT

Mia Cahill,* a 49-year-old female patient, lives with systemic lupus erythematosis, and, fortunately for her, has been spared from many systemic manifestations of the disease.

However, her eye health has not been spared and due to the severity of her ocular manifestations, Ms Cahill has endured bilateral retinopathy, retinal detachments, vaso-occlusive retinal disease, optic neuropathy, and severe dry eye from keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Following multiple corneal transplant rejections, as well as profound bilateral retinopathy, Ms Cahill developed full corneal leukoma and complete bilateral loss of vision. Despite this, with support from Guide Dogs Association and Vision Australia, she was able to continue working.

Ms Cahill was referred by her corneal ophthalmologist for co-management for bandage contact lenses for dry eye, and for consideration of prosthetic contact lenses. She was prescribed a pair of Capricornia Eycon custom hand-painted coloured contact lenses for aesthetic reasons to help her eyes appear normal without scarring, so she feels a sense of normalcy in the workplace. These prosthetic contact lenses also provide relief, as a bandage contact lens for her dry eye. In addition, Ms Cahill was prescribed ocular lubricants to support multiple layers of her tear film and manage dry eye symptoms.

The result? Ms Cahill’s quality of life has improved with her dry eye symptoms being minimised, and she now feels more comfortable in social and work settings.

*Patient name changed for anonymity.

Dr Margaret Lam BOptom UNSW Post Grad OcTherapy practises optometry at 1001 Optometry in Bondi Junction in Sydney and teaches at the School of Optometry at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) as an Adjunct Senior Lecturer. She is a past National President of Optometry Australia.

References available at mivision.com.au.