mifeature

Shaping Sustainable Solutions

Eye Care Workforce Mapping in WA

WRITERS Jingyi Chen, Associate Professor Khyber Alam, Professor Sharon Bentley, Professor Allison McKendrick, Winthrop Professor Marc Tennant, Professor Sandra Thompson, and Professor Angus Turner

Despite health equity initiatives, geographic barriers to timely, accessible, and affordable healthcare persist for one in three Australians who live in rural areas. This article outlines longstanding challenges in rural eye care access in Western Australia (WA) and proposes potential solutions that could be implemented nationwide – and even globally.

Early intervention is critical in the prevention of avoidable blindness; however rural residents experience longer wait times and are often required to travel long distances to access healthcare. Beyond personal inconvenience, reliance on carers, financial cost, and delayed access to care contributes to overall poorer eye health outcomes for rural Australians.

WA is the largest geographic state in Australia, and 540,000 people live across more than two million square kilometres of land in regional and remote areas. For context, WA makes up around one-third of Australia’s land mass, and is larger than France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Greece combined. This large land area, and its sparse population, present unique challenges for eye care workforce coverage across the state.

There is a maldistribution of the eye care workforce, with more optometrists and ophthalmologists working in urban compared to rural areas. Established eye care practices are supplemented by visiting services in more remote areas. State and federal governments, non-governmental organisations, and communities have an opportunity to work together towards sustainable approaches to achieve universal eye health coverage, regardless of geographic location. Ideally, decisions to drive the evolution of health policy and practices should be data-driven; understanding service availability should inform subsequent strategies to address identified gaps. However, the range of service providers, funding sources, and workforce agencies mean the landscape for service provision is fragmented.

Two recent publications, led by the University of Western Australia, provided insights into the longstanding challenges in rural eye care access in WA, and proposed opportunities towards solutions.1,2 The geographic eye care service mapping study1 and qualitative study2 highlighted key opportunities, such as optimising workforce skills, developing collaborative care models between optometry and ophthalmology, expanding telehealth services, and harnessing artificial intelligence (AI).

Supporting the rural eye care workforce through personal, professional, and financial means emerged as important factors for workforce recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. This new knowledge contributes to the ongoing efforts to improve eye care access, offering evidence-based strategies that can help bridge the gap in service provision, not only in rural WA but also in similar underserved settings across the country.

MAPPING THE WORKFORCE

The workforce mapping study illustrated the distribution of the optometry and ophthalmology workforce in rural WA.1 To conduct the study, practices were identified and surveyed regarding workforce hours

and equipment. Visiting service information was captured through the survey and through workforce organisations. A total of 222 services were located and mapped, including 58 optometry practices, eight ophthalmology practices, 113 visiting optometry services, and 43 visiting ophthalmology services. Geographic information systems (GIS) analyses were undertaken, comparing service information with Australian Bureau of Statistics Census population data. The findings showed that eye care services in WA are widely distributed; 93.7% of the population live within 50 km of an eye care service and 97.2% live within 100 km of a service.

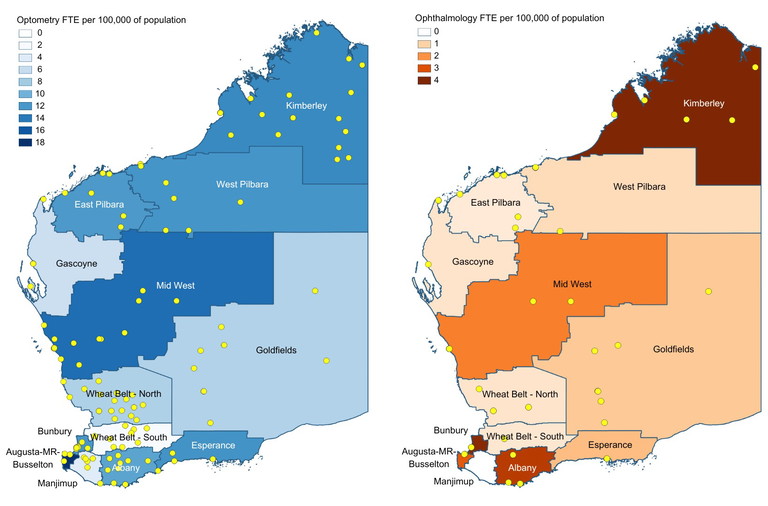

While there was broad coverage of eye care services, workforce-to-population ratio analyses aimed to investigate availability of full-time equivalent (FTE) hours relative to population size. Overall, FTE recommendations are 10 FTE optometrists per 100,000 of the population3 and four FTE ophthalmologists per 100,000 of the population.4 The authors found that of the 13 regions, eight regions met FTE recommendations for optometry and two met FTE recommendations for ophthalmology. Although one of the two regions met ophthalmology FTE recommendations, the data showed that there were only private clinic services available. As a result, patients who required publicly funded ophthalmology care still had to travel long distances to access treatment – a barrier that disproportionately affects those who have carer roles or have limited financial resources.

ACCESS TO EQUIPMENT

Historically, access to equipment in rural areas was challenging. For ophthalmology, the Lions Outback Vision Van, a mobile ophthalmology unit equipped with specialist diagnostic and treatment tools, has played a crucial role in overcoming these obstacles. By bringing state-of-the-art equipment directly to rural communities, the Vision Van has made essential eye care more accessible to 21 of the 32 regional towns.

For optometry, all practices that responded to the equipment survey had a slit lamp and tonometer. The proportion of optometry practices that had a retinal camera was 88.9%, 95.5% had visual field, and 64.4% had optical coherence tomography (OCT). These findings show that the proportion of practices with OCT has tripled in rural WA since 2017, indicating optometrists are increasingly adopting advanced technologies in clinical settings. This positive trend not only facilitates more accurate and timely diagnoses in primary care, but also fosters opportunities for collaborative care with ophthalmologists, enhancing the quality of patient management.

UNDERSTANDING WORKFORCE PERSPECTIVES

In-depth interviews with eye care professionals working in rural areas uncovered barriers affecting access for rural residents. Seventeen participants, including optometrists, ophthalmologists, and non-clinical staff, were interviewed about their perspectives on rural eye care in WA.

Challenges of access for rural residents mentioned in these interviews included wait times, cost of services, and long travel times and distances to access care. Access to advanced diagnostic equipment remained a challenge in some areas. In contrast, outreach services and innovative models, such as collaborative telehealth, were seen as facilitators to eye care access.

Many practitioners cited the opportunity to make a tangible difference as a major motivator for rural practice. Community connection and clinical variety were also seen as rewarding aspects of rural work. Optometrists and ophthalmologists valued the role that the other had to play in the delivery of eye care, appreciating the need for coordination of services, collaboration, and communication to deliver optimal patient outcomes.

However, the challenges were equally clear. Personal and professional isolation, lack of professional development opportunities, time constraints, and the burden of travel, were commonly cited. Another concern was the current Medicare bulk billing model and funding structures for optometry, which practitioners reported inadequately compensate for the management of complex eye conditions or participation in collaborative care models. This financial disincentive may limit the sustainability of comprehensive rural eye care.

“Supporting the rural eye care workforce through personal, professional, and financial means emerged as important factors for workforce recruitment, retention, and satisfaction”

The Lions Outback Vision Van.

Map of eye care workforce FTE per 100,000 of the population, by region in rural and remote WA for optometry (left) and ophthalmology (right). Visiting services and eye care practice locations are indicated by yellow dots for optometry (left) and ophthalmology (right).1

Visitors from Kundat Djaru, also known as Ringer Soak, at the Hub in Broome with Janet Puertollano from Lions Outback Vision (right).

“The future of eye health depends on a coordinated, collaborative, and informed approach to optimising care with community needs at the centre of care planning and delivery”

THE IMPORTANCE OF COLLABORATION

The findings from both studies suggest that collaborative efforts present opportunities for the workforce to address gaps in service delivery. Collaborative care enables more efficient use of the available workforce, reduces duplication, and ensures patients receive timely and appropriate care. Aligning primary and secondary care is of particular importance where resources, such as visiting service availability, are limited. As one ophthalmologist responded in the study, “It’s critical to maximise the efficiency of service delivery in [rural] areas… and making sure that people’s skill sets are used most efficiently where possible”.

Many regions in WA have already developed strong, longstanding, locally driven collaborative care models between optometry and ophthalmology. These partnerships often evolved in direct response to community needs. “I’m in [a very remote area] at the moment and the public waiting list [for ophthalmology] is just huge,” said one optometrist. “We’re working out of the hospital to try and triage and help decrease that list… we see any patients that can be seen by an optometrist … it takes the pressure off the ophthalmologists who visit once a month.”

One prominent collaborative model to reduce public wait lists is telehealth. Collaborative telehealth, led by Lions Outback Vision, enables optometrists to perform a comprehensive in-person examination and seek ophthalmology input without the patient needing to travel or wait for specialist services. “With the advent of telehealth and the willingness for co-management, we have been able to almost completely wipe out the need for patients to unnecessarily travel,” reported an optometrist.

This model of telehealth also allows for direct booking of surgery, avoiding the hidden wait list that often masks the true wait time for procedures such as cataract surgery. However, there are regional differences, with some optometrists working closely with ophthalmology via telehealth daily, whereas other regions have more traditional models of care, relying solely on face-to-face primary and secondary services that are not integrated or coordinated.

TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE RURAL EYE CARE SYSTEM

The need to build sustainable models of care that are accessible and appropriate to meet population needs must include building culturally safe and accessible services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities as a priority. In addition to building the capacity and numbers of the Indigenous eye care workforce, the workforce training lag necessitates creating a non-Indigenous workforce that is culturally aware and responsive. The provision of culturally safe care capacity building in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners, improvements to funding models, and better partnerships, will be fundamental to closing the equity gap in eye health outcomes in Australia.

The findings from both the mapping and workforce studies suggest the need to think innovatively about how eye care is delivered in rural and remote Australia in the present and long term. Addressing service gaps through collaborative, flexible, and community-driven models is essential. There is an opportunity to understand which regions have better eye care access than others and, where possible, apply those learnings to local contexts in other regions.

Lions Outback Vision Ophthalmic Consultant Dr Vaibhav Shah conducts a telehealth appointment.

Members of the eye health team, Aksh Handa, Kerry Woods, Nour Barakat, and Alex Ramirez at the Vision Van.

Eye health professionals Alex Sherrington and Aishwariya Seshakumaran with a patient in the Vision Van.

The use of telehealth and other digital health avenues, such as AI, will become increasingly commonplace in healthcare. Artificial intelligence has potential for a wide range of purposes, including diagnosis, predictive analytics, triage, administration, and patient communication. Eye care professionals need to stay informed and aware of technological developments and be equipped with the knowledge and skills to use technology ethically and appropriately. Entry-level competencies and continuing professional development opportunities will need to evolve accordingly.

Training and upskilling of the workforce will be essential for the future of eye care delivery. Strategic allocation of tasks to members of the workforce with varying levels of training, has been identified by the World Health Organization as a key opportunity to address workforce shortages.5 Health programs and systems around the world are increasingly moving away from profession-defined tasks and towards skills-based competencies that focus on education and training.6

Developing strategies to recruit a rural workforce, and minimise attrition, is vital for the long-term sustainability and health of rural communities around Australia. Rural generalist training pathways exist and are available for general practitioners, nurses, and certain allied health professionals to support them to meet the needs in rural communities. No such pathways currently exist for eye care practitioners in Australia. The greater range of pathology and complex eye disease in rural areas, and the accompanying need for a broader skillset, brings into question whether there is opportunity to have similar training pathways for eye care. Retaining the rural eye care workforce requires ongoing support, including education opportunities, mentoring, financial incentives, and system-level reforms that make collaboration feasible, practical, and rewarding.

THE ROLE OF EVIDENCE TO INFORM PRACTICE AND POLICY

One of the findings of the WA mapping study was that the area of Manjimup, south of Perth, had no ophthalmology services at the time of the study. This led to the establishment of a new eye care service on the Lions Outback Vision Van, which began services in February 2025.

“We’re thrilled to bring the Vision Van to Manjimup for the first time in a rapid response to workforce mapping,” Professor Angus Turner, Director of Lions Outback Vision, commented. “It’s part of our ongoing mission to reduce preventable blindness and vision impairment by ensuring that everyone, no matter where they live, has access to specialist eye care.”

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

WA’s rural and remote regions face complex challenges to accessing equitable eye care, but also offer unique opportunities for innovation. Similar issues exist around the country, even in metropolitan areas, where patients face challenges accessing public eye care. By leveraging insights from workforce mapping and frontline experiences, policymakers and service planners can make evidence-based decisions towards sustainable models of care, not only for WA but across Australia. Research is underway by the authors to evaluate the effectiveness of collaborative care models and telehealth in addressing access barriers to eye care in underserved areas. The future of eye health depends on a coordinated, collaborative, and informed approach to optimising care with community needs at the centre of care planning and delivery.

Jingyi Chen BVisSc MOptom is an optometrist, lecturer, and PhD candidate at the University of Western Australia.

Associate Professor Khyber Alam BVisSc MOptom PhD MBA is the Head of Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences at the School of Health and Clinical Sciences at the University of Western Australia.

Professor Sharon Bentley PhD MPH MOptom FAAO(DipLV) is Professor and Dean at the University of California, Berkeley Herbert Wertheim School of Optometry and Vision Science.

Professor Allison McKendrick BScOptom MScOptom PGCertOcTher PhD is the Lions Eye Institute and UWA Chair in Optometry Research.

Winthrop Professor Marc Tennant BDSc PhD FRACDS (GDP) is the Director and Founder of the International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity at the University of Western Australia.

Professor Sandra Thompson PhD FAFPHM is the Director of the Western Australian Centre for Rural Health (WACRH) and Professor of Rural Health at the University of Western Australia.

Professor Angus Turner MBBS (Hons) MSc FRANZCO is the McCusker Director of Lions Outback Vision and established the Lions Outback Vision Van. He is an internationally recognised pioneer of teleophthalmology.

References

1. Chen J, Alam K, Turner AW, et al. Using geographic information systems to map eye care service distribution in rural and remote Western Australia. BMC Health Serv Rev. 2025; 25:551. doi: 10.1186/s12913-025-12723-8.

2. Chen J, Alam K, Turner AW et al. Rural eye care access, workforce challenges and opportunities: Perspectives of the eye health workforce in Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2025;331(1): e70004. doi: 10.1111/ajr.70004.

3. The role of optometry in vision 2020. Community Eye Health. 2002;15(43):33-6. PMID: 17491876; PMCID: PMC1705887.

4. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists. RANZCO’s vision for Australia’s eye healthcare to 2030 and beyond. 2023. 115p. Available at: ranzco.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/RANZCO-Vision-2030-and-beyond-v2.pdf. [accessed August 2025].

5. World Health Organization. Task shifting: Global recommendations and guidelines. Available at: siris.who. int/bitstream/handle/10665/43821/9789241596312_eng. pdf [accessed August 2025]. 6. World Health Organization. Eye care competency framework. 20 May 2022. Available at: who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048416 [accessed August 2025].