mipatient

Managing the Multiple Implications of Strabismus

WRITER Jessica Chi

Affecting approximately 2–5% of the global population,¹ the implications of strabismus extend beyond visual function. Using case studies, Jessica Chi discusses how prosthetic contact lenses can help – visually, cosmetically, and emotionally.

Acquired strabismus often results in diplopia, which can be debilitating. Patients may experience constant or intermittent double vision that interferes with reading, mobility, and driving. Longstanding strabismus, particularly when acquired in early life, often leads to sensory adaptations, such as suppression to avoid diplopia. This can result in amblyopia and loss of stereopsis, reducing or eliminating depth perception and affecting fine motor tasks, hand-eye coordination, and tasks requiring spatial perception.

Patients frequently report asthenopia, headaches, and visual fatigue during tasks requiring sustained concentration, such as study, work, or sport. These symptoms are particularly bad in those with decompensating intermittent strabismus.

However, the implications of strabismus extend beyond visual function. Psychological, emotional, and social factors often have a profound impact on quality of life. Individuals with strabismus may experience stigma, bullying, and social exclusion, especially during childhood, which can have long-term effects on self-esteem and emotional development.

Individuals with strabismus may be perceived as unattractive, unintelligent, and lazy.

Adults often report social anxiety, reduced confidence in professional interactions, and avoidance of eye contact. They may find it more difficult to create relationships, obtain and keep jobs, and attain promotions.2

Quality of life surveys have found that those with strabismus score less than normal in all quality of life and all vision-related subscales, with or without diplopia. Both children and adults are at least 10% more likely to suffer from clinical depression, and 10 times more likely to suffer from clinical anxiety.3 At least half of adults suffering from strabismus experience social phobia.2 Some individuals adopt compensatory behaviours – such as changing head posture, covering the affected eye with hair, or avoiding eye contact and social settings – which can further reinforce social isolation.

CASE ONE: IRIS-PRINT CONTACT LENS

Tina O’Reilly,* a 43-year-old female, was diagnosed with a large petroclival meningioma four months prior, which was subsequently removed one week later. Fortunately, the surgery was successful, with most of the lesion found to be benign and removed. Unfortunately, during surgery she suffered a sixth nerve palsy, resulting in an inability to abduct her right eye, which caused her constant diplopia.

She did not wear spectacles and, to manage her diplopia at work, she wore a patch over her right eye and used her hair to cover that side of her face.

• Visual acuity (unaided): R 6/9, L 6/6.

• Refraction: R +1.00 / –0.50 × 80 (6/6), L plano.

• Ocular health: Unremarkable.

Ms O’Reilly was trialled with soft lenses featuring a black pupil in two sizes (4 mm and 7 mm). Neither fully occluded her vision, resulting in persistent visual disturbance. Additionally, the 7 mm black pupil appeared conspicuous and unsightly against her hazel irises.

“Individuals with strabismus may experience stigma, bullying, and social exclusion, especially during childhood”

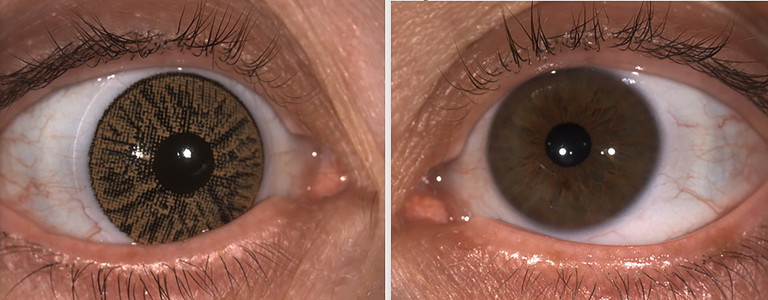

Figure 1. Patient’s right eye fitted with the Capricornia Eycolour Prosthetics iris-print prosthetic soft contact lens.

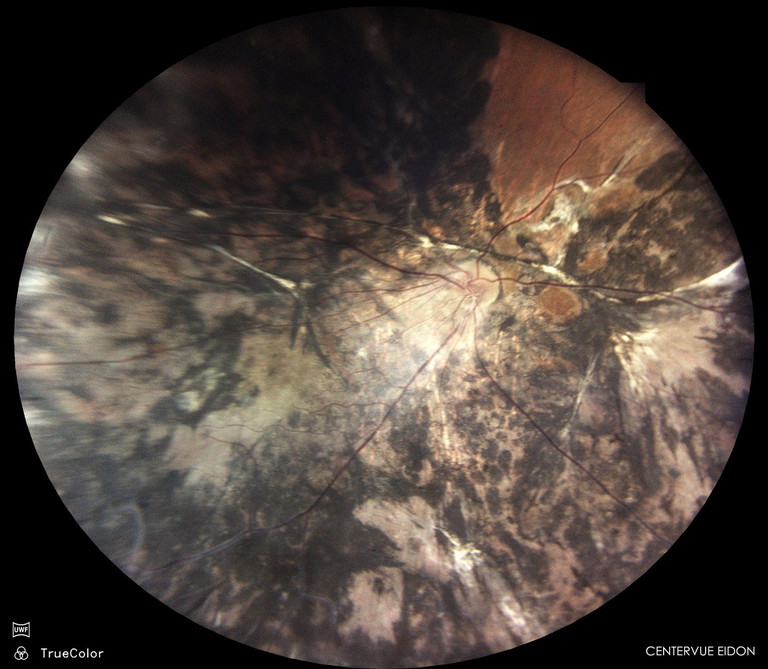

Figure 2. Fundus photography showing optic disc pallor, widespread atrophy, and scarring as a result of retinopathy of prematurity.

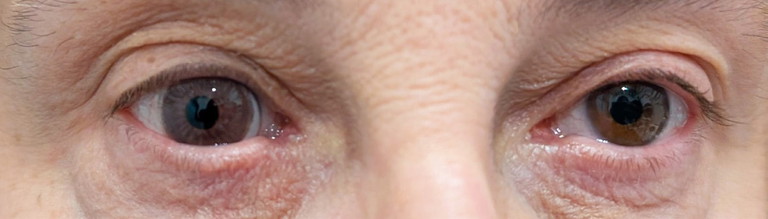

Figure 3. Patient with esotropia.

Figure 4. Hand-painted prosthetic soft contact lens with temporally displaced iris.

She was subsequently fitted with a Capricornia Eycolour Prosthetics iris-print prosthetic soft contact lens, incorporating a black pupil for her right eye. The colour match was adequate (Figure 1), and the prosthetic’s opaque backing effectively occluded her vision.

Ms O’Reilly, a lawyer, had not been working due to feeling self-conscious about wearing a patch in client-facing situations. The prosthetic lens provided full occlusion comparable to the patch, but offered superior aesthetics and visual comfort, as the patch had also obstructed part of her left eye’s visual field.

This restored her confidence and enabled her to return to work. Because her right eye continued to exhibit a constant esotropia, she preferred to keep her hair draped over the eye to conceal this. She was hopeful for spontaneous recovery of her palsy and was satisfied with the temporary cosmetic match.

CASE TWO: ARTIFICIALLY SHIFTING THE IRIS

Linda Gambrill,* a 53-year-old female, presented seeking improved cosmesis for her right esotropia. She was born prematurely at 31 weeks and placed on supplemental oxygen. Although she survived, she developed retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) in her right eye. Fundus examination revealed optic disc pallor, extensive chorioretinal scarring, pigmentary disturbance, fibrotic traction, attenuated vessels, macular dragging, and widespread pigmentary atrophy (Figure 2). She was left with minimal vision in the right eye and a subsequent constant right esotropia.

Ms Gambrill had undergone two squint surgeries during childhood; both were unsuccessful (Figure 3). She remained extremely self-conscious of her strabismus, avoiding eye contact and struggling to maintain employment. She grew her hair long to conceal her eyes and reduce the visibility of the deviation.

Vision: R light perception (LP), L 6/5.

Ms Gambrill was prescribed a hand-painted prosthetic soft contact lens manufactured by Capricornia. The lens was a Nutoric design with a reverse prism – featuring offset prism on either side – and parameters of back optic zone radius (BOZR) 8.10 mm and diameter 15.0 mm. The iris was displaced temporally (Figure 4), creating the cosmetic effect of realigning the right eye by artificially shifting the iris position (Figure 5).

SIMPLE SOLUTIONS

Strabismus is a multifaceted condition that extends well beyond ocular misalignment. Its impact includes visual disability, reduced stereopsis, psychosocial stigma, and functional limitations that collectively reduce quality of life. If left unaddressed, the emotional burden can lead to social withdrawal, anxiety, and depression.

Far more than a cosmetic concern, it affects how a person sees, functions, and perceives themselves. Fortunately, a treatment as simple as a soft contact lens can dramatically improve both vision and psychosocial wellbeing, and can support patients in regaining confidence and comfort in daily life.

Figure 5. The displaced iris created the cosmetic effect of realigning the right eye.

*Patient names changed for anonymity.

Jessica Chi is the Director of Eyetech Optometrists, an independent speciality contact lens practice in Melbourne. She is the current Victorian, and a past National President of the Cornea and Contact Lens Society. She is a clinical supervisor at the University of Melbourne, a member of Optometry Victoria Optometric Sector Advisory Group, and a Fellow of the Australian College of Optometry, the British Contact Lens Association, and the International Academy of Orthokeratology and Myopia Control.

References

1. Kanukollu VM, Sood G. Strabismus. [Updated 2023 Nov 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560782.

2. Buffenn AN, The impact of strabismus on psychosocial health and quality of life: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021 Nov-Dec;66(6):1051-1064. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.03.005.

3. Adams GG, McBain H, Newman SP, et al. Is strabismus the only problem? Psychological issues surrounding strabismus surgery. J AAPOS. 2016 Oct;20(5):383-386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2016.07.221.