mieducation

Refining Normative Eye Models: From Outliers to Precision

Standard eye models assume we’re all average – but we’re not. When biometric outliers and anatomical scatter distort our normative data, every lens calculation inherits that error. In this article, Dr Grant Hannaford explores how cleaning datasets and conditioning models to actual prescriptions transforms the ‘textbook eye’ into a clinically useful, probabilistic tool for better optical outcomes.

WRITER Dr Grant Hannaford

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this CPD article participants should be able to:

1. Evaluate the clinical impact of biometric outliers on lens design accuracy,

2. Apply multivariate biometric analysis to predict optical performance of a lens on eye,

3. Calculate and interpret residual off-axis astigmatism penalties, and

4. Integrate biometric distribution data into clinical decision making.

Normative eye models, from Gullstrand’s classical multi-surface construction to modern aspheric and gradient-index variations, have long served as the foundation for lens design, intraocular lens (IOL) prediction, and clinical optics.1 They allow us to simulate how an idealised, emmetropic eye behaves. Yet in clinic, even in the absence of refractive error, no two eyes are truly average. Scatter in axial length (AL), corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth (ACD), and lens geometry means that applying one ‘standard’ eye to everyone bakes error into our optical decisions.

The shift we need is simple to state and non-trivial to execute: take population-level models and refine them with cleaned biometric data tied to the actual prescription in front of us. Done properly, the ‘normative eye’ becomes a probabilistic, prescription-conditioned eye, not a single schematic. Every failed estimation in biometry moves a refractive prediction, and the downstream optical solution you select for your patient.

THE OUTLIER PROBLEM AND DATA CLEANING

Real-world biometric datasets carry noise: failed scans, transcription errors, duplicate patients, and true anatomical outliers.2 Left unfiltered, outliers distort means and broaden standard deviations, which then propagate through any model that maps refractive error to anatomy and back again to lens design. This issue can render biometric models effectively unusable, as extreme values may pull the model far from those that reflect the broader population norms.

For example, consider a dataset of 1,200 eyes with a typical axial length range of 22.0–27.0 mm. If two faulty scans record values of 33.5 mm and 34.0 mm, well outside physiological plausibility for this population, the calculated mean shifts upward and the standard deviation widens.3 A model built on this dataset will predict longer eyes than are reasonable, particularly for moderate myopes. The flow-on effect is a less accurate relationship between spherical equivalent (SE) and axial length (AL), and ultimately, poorer guidance for lens design.

The solution most commonly used is systematic data cleaning. Implausible values (e.g., AL shorter than 18 mm or longer than 32 mm) can be flagged and removed. Duplicate patient records will be consolidated so that a single eye is not weighted multiple times. Genuine outliers, such as a highly pathological or post-surgical eye, may be retained but analysed separately, ensuring they do not distort the normative model. Consequently, data cleaning is not an academic exercise; it is clinical risk reduction. By excluding errors and isolating rare cases, the resulting distributions become sharper and more representative. This, in turn, refines the ‘most probable’ biometric profile for each prescription, which is the foundation for more reliable clinical decision making. Cleaning the data isn’t just statistics, it’s the difference between a lens that quietly works, and one that becomes a comfort or clarity problem that impinges on the patient’s awareness.

BEYOND AL: INFERENCE FROM THE FULL BIOMETRIC PROFILE

When discussing biometry and lens design, axial length provides the most immediately recognisable relationship. It tracks intuitively with SE: longer eyes are generally more myopic, and shorter eyes more hyperopic.4 This makes AL the most straightforward metric for articles, graphs, and patient conversations. However, to reduce the eye to a single number is to oversimplify a highly complex optical system, so a holistic approach to modelling the eye is preferred.

Biometry is inherently multivariate. Two eyes with the same refractive error, for example, a pair of -2.00D eyes, may arrive at that prescription through very different anatomical pathways. One eye may have a slightly elongated axial length with a relatively flat cornea, while another could display an average axial length but a steeper corneal curvature or thinner crystalline lens. The net spherical equivalent may be the same, but the way each eye transmits light is fundamentally different.

Anterior chamber depth (ACD) is another well-known variable demonstrating linkages between biometry and refractive error.5 A -2.00D eye with a deep ACD will present different effective lens position and vergence behaviour than one with a shallow anterior chamber, even if the axial length is identical. These differences affect peripheral focus, susceptibility to higher-order aberrations, and even surgical planning in refractive or cataract procedures. Similarly, lens asphericity and thickness influence how the eye balances on-axis clarity with off-axis sharpness, impacting progressive lens tolerance and peripheral image quality.

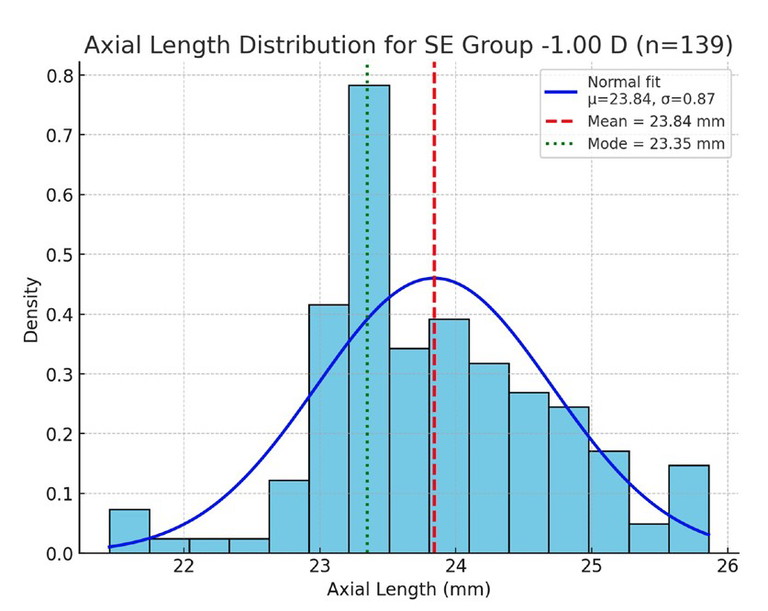

Figure 1. Axial length distribution for the -1.00D SE group. Blue bars show the histogram; the fitted normal curve is overlaid in blue; the mean (red dashed line) and mode (green dotted line) are marked.

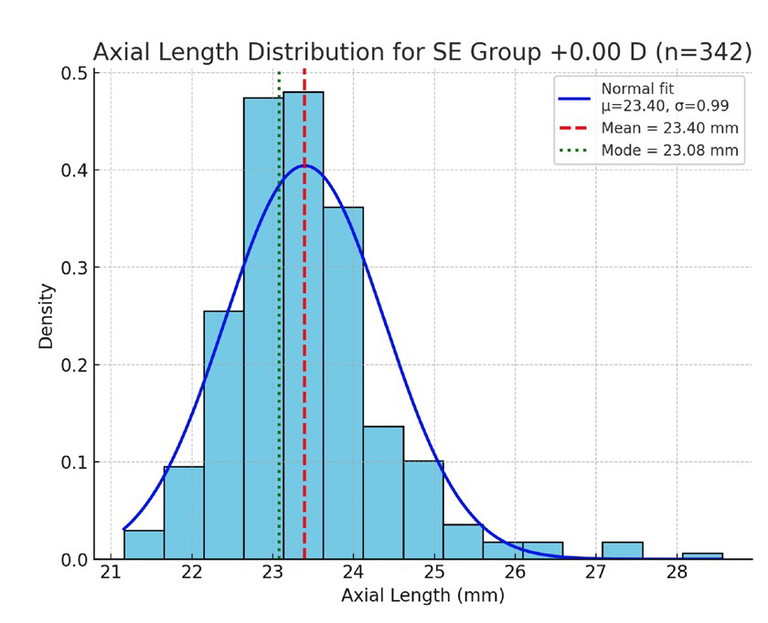

Figure 2. Axial length distribution for the 0.00D SE group (emmetropes), with normal curve, mean, and mode markers as above.

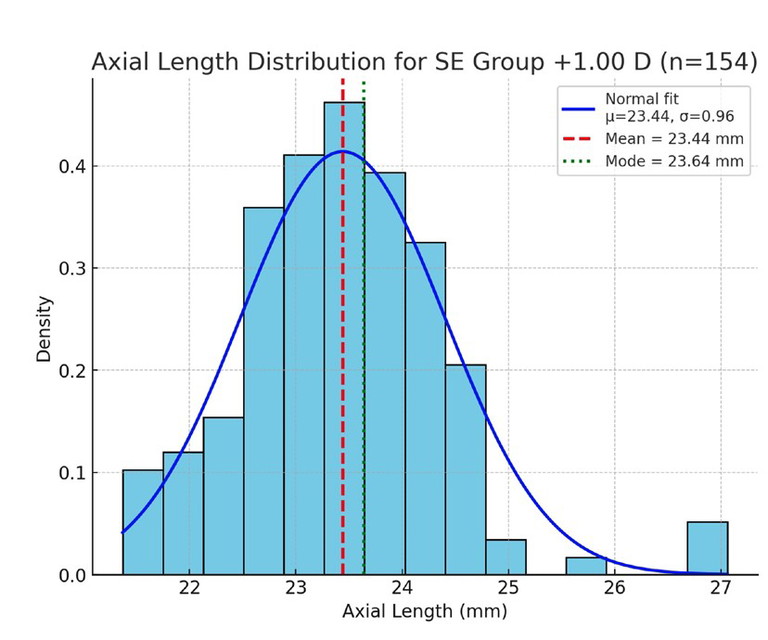

Figure 3. Axial length distribution for the +1.00D SE group, showing clustering around shorter axial lengths.

Good normative modelling takes account of these interdependencies. Instead of treating AL, cornea, ACD, and lens characteristics as isolated descriptors, robust models recognise them as a joint biometric signature. Incorporating multiple dimensions allows us to more consistently infer how a given prescription maps to an actual anatomical configuration. For instance, an AL of 24.0 mm paired with a steep cornea might predict different peripheral astigmatism behaviour than the same AL with a flatter cornea. These nuances matter for lens design, particularly in high prescriptions and customised optics where small mismatches between model and anatomy can translate into noticeable blur or discomfort.

Finally, higher-order aberrations (HOAs) are being shown to be increasingly relevant in lens design.6 An eye that is optically ‘average’ in AL and corneal curvature may still diverge significantly in coma, spherical aberration, or trefoil. Including HOAs in normative modelling offers a more complete prediction of image quality across the visual field, and further underscores that biometry is not one-dimensional.

In short, axial length tells an important story, but it is only one element. The full picture emerges when AL is read alongside corneal shape, anterior chamber geometry, crystalline lens form, and wavefront aberrations.

Together, these variables provide a richer, more clinically useful map of the eye, and this is where normative modelling truly demonstrates its power. Normative models become clinically powerful when they mirror not the average eye, but the most probable eye for a given prescription across all relevant biometric dimensions.

PENALTIES OF INAPPROPRIATE EYE MODELS

One effective way to illustrate the optical penalty of relying on an unsuitable eye model is to assess the residual off-axis astigmatism that results from the mismatch. This situation arises, for example, when a lens is designed under the assumption of emmetropia, even though the patient is, in fact, a moderate myope with very different ocular geometry. The discrepancy between the assumed and actual eye shape means that the design does not fully compensate for peripheral optics, leaving behind measurable astigmatism in the visual field.

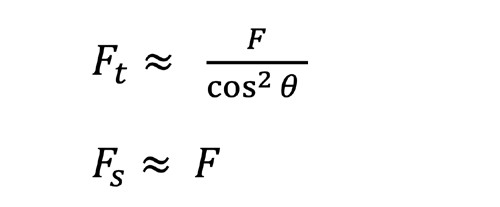

A simply calculated, conservative estimate comes from the oblique astigmatism of a spherical correction at a field angle θ. For a thin lens focussed at optical infinity with the lens treated as a bare refractor (i.e. no lens form or ‘best form’), the tangential and sagittal powers may be approximated as an angular function:

The residual cylinder is therefore F_t - F_s. Importantly, this is not a full Tscherning analysis using methods such as the Coddington equations, and cannot replace full freeform optimisation.7 It provides a useful worst case bound for the error introduced by a poorly implemented design, particularly when a schematic model eye leads to the wrong base curve choice, or omits aspheric/atoric compensation. Furthermore, it highlights the power of appropriate lens form selection in the amelioration of aberrations, a process that is refined through appropriate modelling of the visual system.

Table 1. Sample calculations of off-axis astigmatism due to model eye discrepancies.

Designing as if the eye follows an emmetropic model, when it is in fact -2.00 to -3.00D, means the optical system no longer delivers a true point focus for the real eye. The practical outcome is additional off-axis cylinder, often reaching clinically significant levels at 25–30°, exactly where progressive lens corridors and near vision tasks occur. The example calculations in Table 1 illustrate how even moderate myopia can generate significant residual astigmatism at peripheral field angles if lens form is not chosen appropriately.

This is where refined, prescription-conditioned normative models, built from cleaned appropriate biometric data, become critical. They can, at the very least, guide base curve selection and aspheric/atoric design toward the actual patient eye, rather than the idealised schematic of a textbook.

WHAT THE SAMPLE DATA SHOW

To highlight how biometric distributions vary across refractive states, axial length was examined within SE refractive error groupings of -1.00D, 0.00D, and +1.00D (rounded to the nearest 0.50D). Histograms of axial length in each group (Figures 1–3) demonstrate distributions that approximate normal curves, with clear clustering around central means.

For the -1.00D group (n=139), the mean axial length was 23.84 mm (spread (σ)=0.87 mm), compared to 23.40 mm (σ=0.99 mm) in the emmetropic 0.00D group (n=342). The +1.00D group (n=154) showed a mean of 23.44 mm (σ=0.96 mm), although the mode was slightly longer at 23.64 mm. These results are consistent with biological variability, with each distribution forming a bell-shaped curve centred near the expected mean.

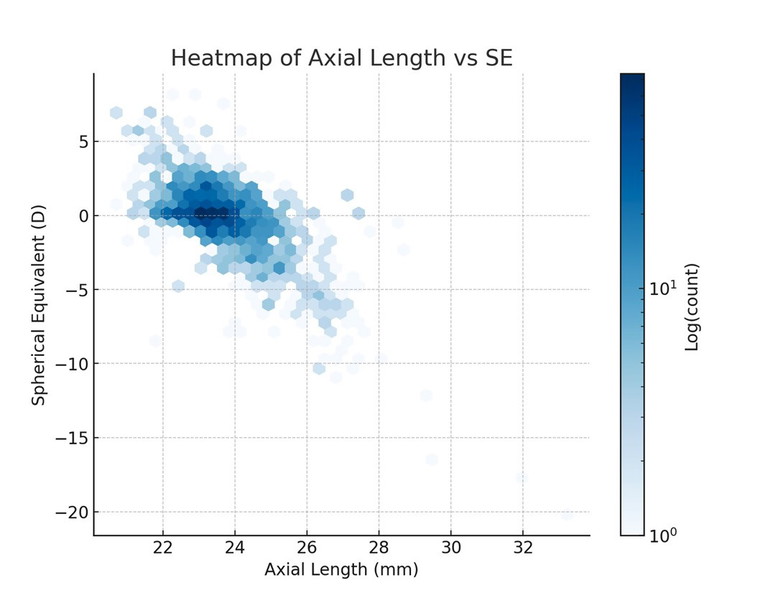

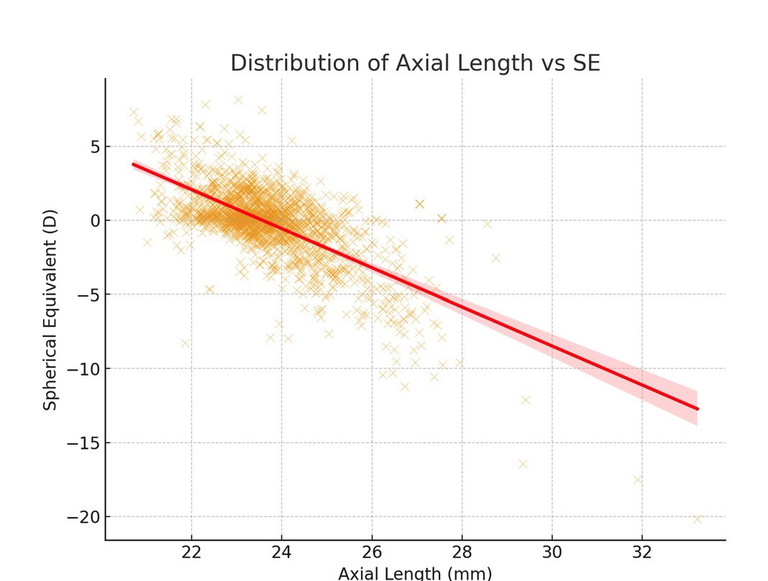

Beyond single refractive groupings, it is also useful to visualise the joint distribution of axial length and refractive error across the whole dataset. A heatmap (Figure 4) illustrates the density of cases within the AL–SE plane, making clear where the data cluster is and how the central tendency shifts with refractive category. Complementing this, a scatterplot of AL vs SE (Figure 5) shows the underlying distribution at the individual level, with a visible negative trend indicating that longer eyes are generally associated with increasing myopia.8

From a clinical optics perspective, these normative distributions have practical significance for lens design. The fact that different refractive error categories cluster around characteristic axial length values means that off-axis aberrations, magnification effects, and field curvature will vary systematically between groups. For example, a moderate myope with an axial length close to 24 mm will present different peripheral optical challenges than an emmetrope or a low hyperope with shorter ocular dimensions. Embedding such normative biometric ranges into design models enables manufacturers to anticipate these differences, optimise base curves and asphericity, and reduce residual astigmatism. In this way, incorporating biometric distributions into the design process supports the development of lenses that more closely match the wearer’s ocular geometry, enhancing both visual quality and patient comfort.

Figure 4. Heatmap of axial length versus SE across the dataset, illustrating where cases cluster in the biometric–refractive plane.

Figure 5. Scatterplot of axial length against SE, showing the overall negative correlation between refractive error and eye size.

“Refined normative models are about bringing the population model down to chairside reality”

USING THIS DATA IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

These plots and distributions are not just academic. They provide clear, practical guardrails for clinical work.

Sanity/validation checks. When biometry is available, compare the measured AL against the expected mean for that prescription grouping (+0.50D, -1.50D etc). Large deviations may signal measurement error or an unusual anatomical case requiring special consideration.

Fallback estimates. When biometry is missing, the mean for each refractive error grouping provides a more narrowly defined default estimate for AL (and by extension, likely anterior segment dimensions). This is particularly valuable in screening, retrospective audits, or when equipment is unavailable.

Lens design decisions. The spread (σ) within each refractive error grouping highlights when to expect variability. Narrow power grouping ranges support predictable base curve and aspheric/ atoric choices, while wide groupings suggest greater caution and the need for additional measurements (ACD, corneal curvature).

Myopia management. In progressive myopes, tracking AL against expected norms for their prescription helps quantify whether elongation is within the ‘probable’ range or diverging toward higher risk.

Patient communication. Heatmaps and histograms can be shown to patients or parents to explain where their eye sits compared to others with similar prescriptions, making discussions of risk and intervention more tangible.

CONCLUSION

Refined normative models are about bringing the population model down to chairside reality. Clean the data, group by prescription, extract the most probable anatomy per grouping, and then design to that eye – not an average. Use the full biometric set when available; use your local priors when you don’t. The reward is predictable clarity, fewer remakes, and better patient experiences.

To earn your CD hours from this activity, visit mieducation.com/refining-normative-ey-emodels-from-outliers-to-precision.

References

1. Rayamajhi AH, Helmer M, Hetz M, Cornelius N. The human eye: From Gullstrand’s eye model to ray tracing today. Lux junior 2021. doi.org/10.22032/dbt.493292.

2. Maccio VJ, Chiang F, Down DG. Models for distributed, large scale data cleaning in Pacific-Asia Conference on knowledge discovery and data. 2014, Springer: 409-421.

3. Hannaford GD, Calibration dataset for biometry measurement [Unpublished data set], Hannaford Eyewear, Editor. 2024.

4. Rozema JJ, Atchison DA, Tassignon MJ. Statistical eye model for normal eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Jun 23;52(7):4525-33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6705.

5. Roy A, Kar M, Mandal D, Ray RS, Kar C. Variation of axial ocular dimensions with age, sex, height, BMI-and their relation to refractive status. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 Jan;9(1):AC01-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/10555.5445.

6. Villegas EA, Alcón E, Artal P. Impact of positive coupling of the eye's trefoil and coma in retinal image quality and visual acuity. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2012 Aug 1;29(8):1667-72. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.29.001667.

7. Jalie M. Principles of Ophthalmic Lenses. 5th Edition, Association of British Dispensing Opticians, 2016.

8. Rozema JJ. Refractive development I: Biometric changes during emmetropisation. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2023 May;43(3):347-367. doi: 10.1111/opo.13094.

Dr Grant Hannaford DOphSc FBDO SLD (Hons) BSc BA (Hons) is a senior lecturer at the School of Optometry and Vision Science University of New South Wales, adjunct lecturer at the Save Sight Institute University of Sydney, and co-owns the multi-award-winning independent optometry practice Hannaford Eyewear as well as the Academy of Advanced Ophthalmic Optics. He was the SILMO and International Opticians Association’s 2022 International Optician of the Year and researches emmetropisation and ocular biometric development in children, and lens design.