mieyecare

When Half a Disc Tells All

Superior Segmental Optic Nerve Hypoplasia

WRITER Nicola Lee

Not every thinned rim or cupped disc signals glaucoma. In this article, Nicola Lee explores how a rare congenital anomaly – superior segmental optic nerve hypoplasia (SSONH) – can closely imitate glaucomatous damage, even on optical coherence tomography (OCT) and visual field testing.

It was meant to be a ‘simple’ patient to finish your clinic day: young and visually asymptomatic, only presenting for a routine eye examination. Best correctable visual acuities 6/6, intraocular pressures within the normative range, and an unremarkable anterior segment. Reaching for your fundoscopy lens, you look through the slit lamp and stare at the optic disc before you. Average size, medium cup, but why is that superior rim so thin?

Your heart beats faster and you whisk the patient towards the OCT, only to find the superior retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GC-IPL) thicknesses are all flagged red as being thinner.

Sighing, you sit the patient down for visual fields assessment, and the results presented before you show a dense inferior arcuate defect. Noting structure-function concordance, the clinical picture seems like glaucoma, but is it really?

This optic disc has all the ‘hallmark’ signs of glaucoma: a thinned rim, suspicious cupping with enlarged cup-to-disc ratio, RNFL loss, and a corresponding visual field defect – but is the diagnosis that simple? As we know, glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although disc cupping may certainly raise red flags for glaucoma suspicion, it is important to recognise that it is not a diagnostic feature on its own. Therefore, clinicians need to systematically evaluate the entire clinical picture and perform a careful examination of the disc to identify other signs that may be suggestive of a non-glaucomatous cause, such as disc pallor.

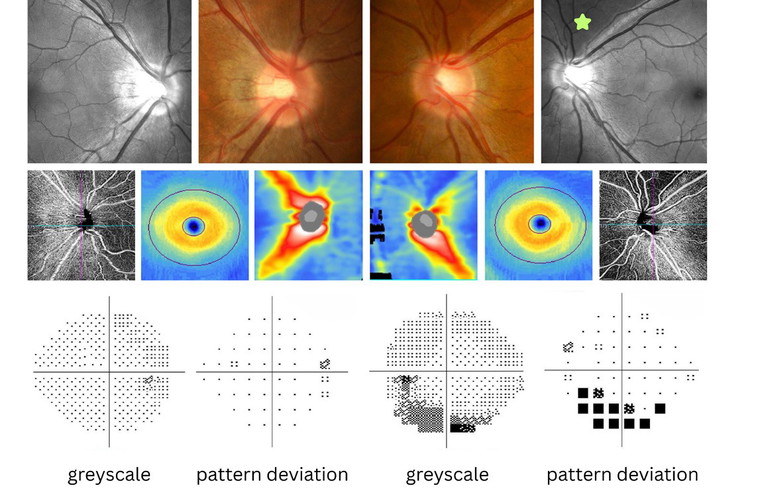

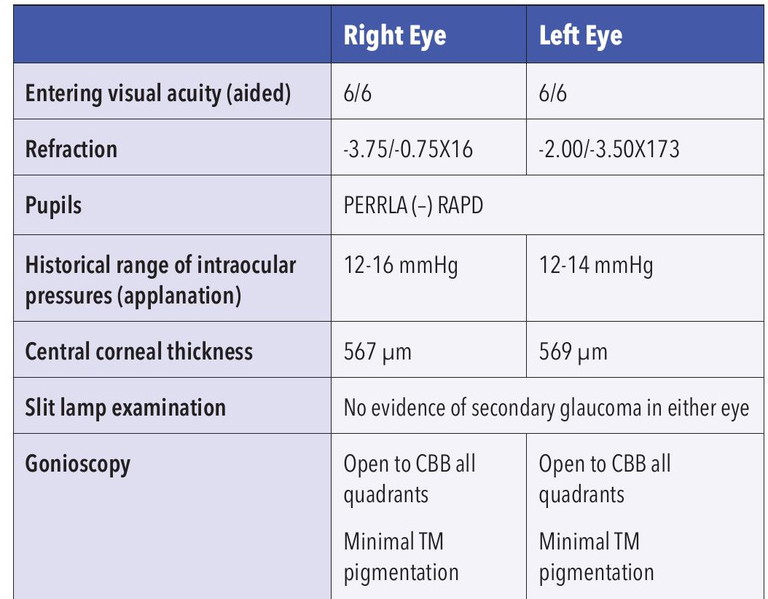

Figure 1. Structural and functional results for Mr Ito. The right optic disc has intact neuroretinal rims and RNFL reflectivity, with no RNFL or GC-IPL defects on OCT. It shows no visual field defects on 24-2 testing. The left optic disc has a thin superior rim with marked reduction in superior RNFL reflectivity (green star) and superior RNFL thickness on OCT, reduced superior peripapillary capillary density on OCT angiography, and a dense inferior arcuate defect extending from the blind spot on 24-2 testing.

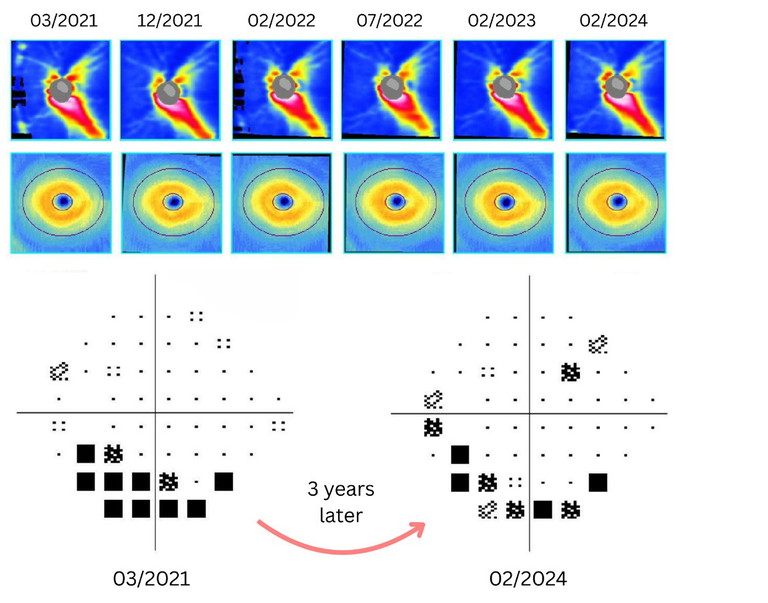

Figure 2. Stable RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses and inferior arcuate visual field defect for Mr Ito over a three-year period.

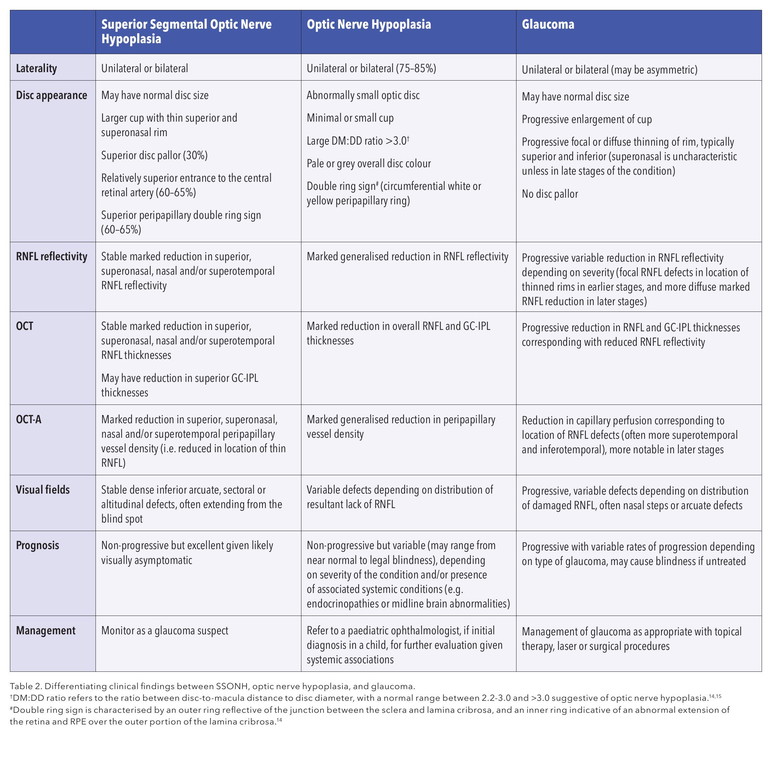

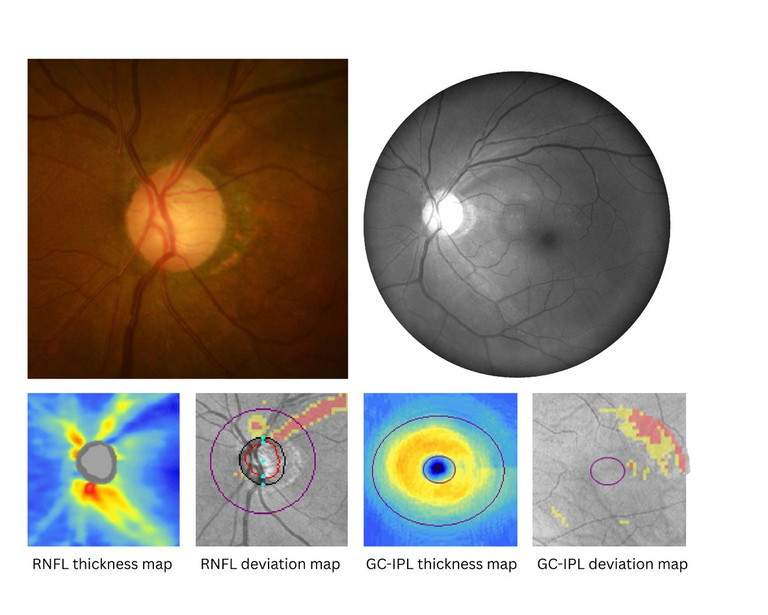

Table 1. Clinical examination findings for Mr Ito. Abbreviations: VA (visual acuity); PERRLA (pupils equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation); RAPD (relative afferent pupillary defect); CBB (ciliary body band); TM (trabecular meshwork).

CASE STUDY

Dylan Ito,* a 33-year-old East Asian male, was referred to the Centre for Eye Health (CFEH) in March 2021 for a glaucoma assessment by his local optometrist. Prior to being referred to CFEH, he was identified as a left glaucoma suspect by a private eye care practitioner in 2019, with a recommendation for a two-year ophthalmology review given stability. He was unable to continue private care for financial reasons, so was reviewed routinely at CFEH until February 2024.

He was visually asymptomatic. His medical history was unremarkable. His ocular history included previous left strabismus surgery and patching for amblyopia at age five. His family ocular history was notable for glaucoma in his maternal aunt. There was no known history of premature birth, low birth weight or maternal diabetes.

The clinical examination findings are shown in Table 1. Fundoscopic examination, visual fields, and imaging results are illustrated in Figure 1, showing a case of unilateral left superior segmental optic nerve hypoplasia (SSONH), with no evidence of structural or functional progression over a three-year period as shown in Figure 2. Considering the stability, he was discharged to his local optometrist for routine optometric review within their practice.

SUPERIOR SEGMENTAL OPTIC NERVE HYPOPLASIA

Superior segmental optic nerve hypoplasia (SSONH) is an important differential diagnosis for glaucoma that needs to be considered. This condition is a unique subtype of optic nerve hypoplasia, whereby there is selective underdevelopment of the superior retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their axons (retinal nerve fibre layers, RNFL). Although it is a unique congenital anomaly where the superior portion of the optic nerve fails to develop correctly, SSONH is often an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients. In a busy optometry clinic, its potential structural resemblance to glaucoma highlights the need to understand and recognise its distinct features to prevent misdiagnosis.

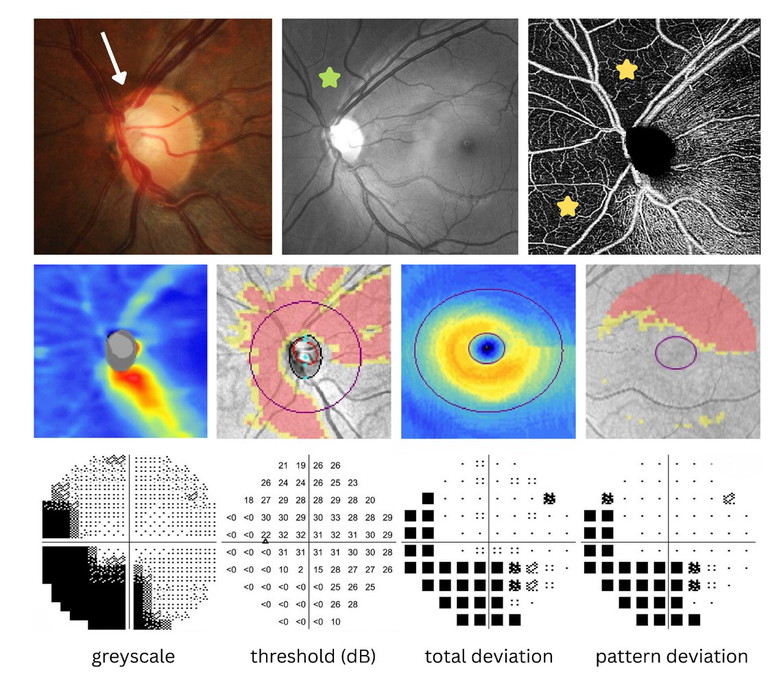

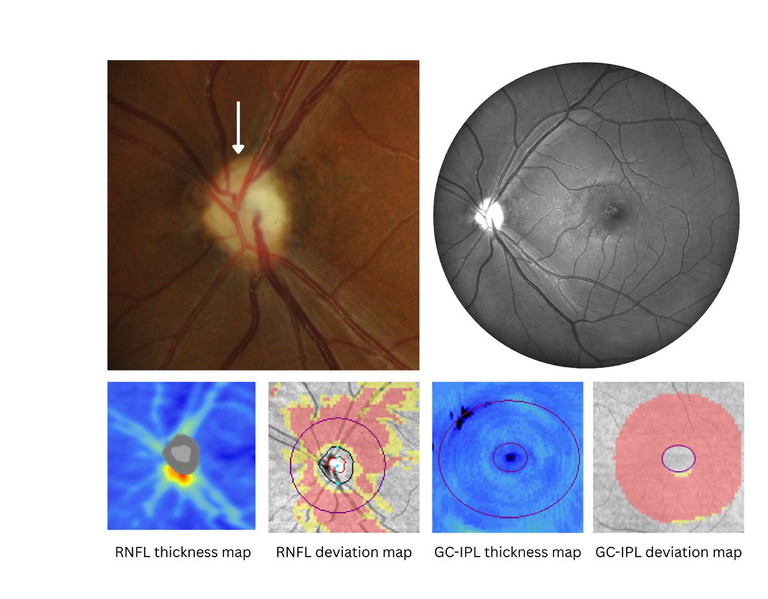

Figure 3. A case of left superior segmental optic nerve hypoplasia (SSONH). Note the average size of the optic disc with a thin and pale superior neuroretinal rim (white arrow), with reduced RNFL reflectivity in the superior and superonasal peripapillary region (green star). There is a reduction in capillary perfusion in the superior, superonasal and nasal peripapillary region on OCT angiography (yellow stars). There is a significant reduction in superonasal, superior and superotemporal RNFL thicknesses and GC-IPL thicknesses on OCT. 30-2 visual fields testing shows a dense inferior arcuate defect extending from the blind spot, also with superior extension of the blind spot.

SSONH was first described in a case study of 17 patients by Petersen and Walton in 1977, and its current name was coined by Kim et al. in 1989, although it may also be known colloquially as ‘topless disc syndrome’ as per Hoyt.1-3

The exact pathogenesis is somewhat of a mystery, although hypotheses regarding excessive apoptosis during gestational development have been proposed, considering that low birth weight and premature birth have been identified as risk factors.4-6There is also a potential association with maternal insulin-dependent diabetes.1-4

SSONH has been reported to affect 0.3% of Japanese patients between 2000–2001, and as few as 0.008% of Korean patients.6 The exact prevalence of SSONH is likely underestimated, as patients are often visually asymptomatic and its clinical presentation may be missed or mistaken for other conditions due to low levels of SSONH awareness among clinicians.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Fundoscopy

There are four fundoscopic features that are typical of SSONH, although their presence has been reported as variable within affected eyes.6 SSONH may be unilateral or bilateral and is ubiquitously characterised by thin superior and superonasal neuroretinal rims with markedly reduced superior RNFL reflectivity.

The presence of associated superior disc pallor varies, being reported in 30% of cases. A superior entrance to the central retinal artery is noted in 60–65% of cases and a superior peripapillary halo (superior or partial ‘double ring’ sign) documented in 60–65% of cases.5-9All structural changes are localised to the superior portion of the optic nerve head, as illustrated by Figure 3.

OCT and OCT Angiography

On OCT, there is a marked reduction in superior, superonasal, and nasal and/or superotemporal RNFL thicknesses (and possibly in superior GC-IPL thicknesses), which is non-progressive.10-11 Other studies have identified a larger degree of ‘overhanging’ of the RPE-Bruch’s membrane complex over the edge of the lamina cribrosa in SSONH eyes (125–558 µm) in comparison to normal eyes (0–99 µm) on spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT), although this may not necessarily be a feature of considerable benefit to assess for in a clinical setting.7,12

“Although disc cupping may certainly raise red flags for glaucoma suspicion, it is important to recognise that it is not a solely diagnostic feature on its own”

Figure 4. A case of left optic nerve hypoplasia. Note the small size of the optic disc with generalised pallor, minimal cupping, ‘double ring’ sign (white arrow), and reduced RNFL reflectivity. There is a marked overall reduction in RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses on OCT.

Figure 5. A case of left normal tension glaucoma. Note the thin superior neuroretinal rim with adjacent superior RNFL defect, and absence of disc pallor. There is a superior RNFL defect and slightly reduced inferior RNFL thickness, with corresponding reduction in both the superior/superotemporal and inferotemporal GC-IPL thicknesses on OCT.

On OCT angiography (OCT-A), there is a reduction in superior, superonasal, nasal and/ or superotemporal peripapillary capillary vessel density noted, corresponding to the location of reduced RNFL thicknesses.6,13

Visual Fields Assessment

A non-progressive dense inferior sectoral, arcuate or altitudinal defect, often extending from the blind spot and corresponding with the marked reduction in superior RNFL thicknesses is typical of this condition.7,9-11

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS WITH OPTIC NERVE HYPOPLASIA AND GLAUCOMA

Table 2 illustrates a summary of examination findings in the three conditions.

Optic Nerve Hypoplasia

Optic nerve hypoplasia is a congenital underdevelopment of the optic nerve, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of RGC axons. The condition is non-progressive, although it may occur in isolation or in conjunction with strabismus, microphthalmos, aniridia, coloboma, nystagmus, facial anomalies, septo-optic dysplasia with midline brain abnormalities, and endocrinopathies (e.g. hypopituitarism).14,15 Thus, a diagnosis of optic nerve hypoplasia in children requires onward referral to a paediatric ophthalmologist for further evaluation.

Clinically, optic nerve hypoplasia may be unilateral or more commonly bilateral (75–85%). It classically presents with an abnormally smaller than average optic disc, minimal or small cup, a larger discto-macula (DM) distance to disc diameter (DD) ratio (DM:DD >3.0), pale or grey disc colour, a ‘double ring’ sign (circumferential white or yellow peripapillary ring), and generalised reduced RNFL reflectivity on fundoscopic examination.14 OCT shows a marked reduction in overall RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses, as seen in Figure 4. Functionally, the degree of visual impairment and visual field loss is variable, with the pattern of functional loss dependent upon the distribution of the lacking RNFL and/or presence of other associated conditions.14,15

Therefore, key distinguishing features for differential diagnosis with SSONH include the small pale disc with minimal cup with circumferential ‘double ring’ sign in optic nerve hypoplasia, contrasted with a variable disc size and larger cup with thinned superior and superonasal rims, and superior or partial ‘double ring sign’ in SSONH. Furthermore, OCT shows generally reduced RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses that are not specific to the superior and superonasal region in optic nerve hypoplasia.

Glaucoma

In contrast to the non-progressive SSONH, glaucoma is a progressive condition and a leading cause of irreversible blindness. Therefore, differentiating the two conditions is essential to ensure accurate diagnosis to allow for timely intervention in glaucoma to improve a patient’s visual prognosis.

Glaucoma is a bilateral and asymmetric progressive optic neuropathy characterised by structural changes to the optic nerve head (neuroretinal rim thinning, enlargement of cup:disc ratio and deepening of the optic cup) due to damage of RGC axons. It is often accompanied by corresponding functional visual field defects. Figure 5 shows an example of glaucomatous structural changes.

“There are four fundoscopic features which are typical of SSONH, although their presence has been reported as variable within affected eyes”

Considering that SSONH presents with a thin superior rim with reduced superior RNFL thickness and corresponding inferior visual field defects, the features may be similar, and careful examination is warranted to differentiate SSONH with glaucoma.

As noted above, SSONH is often an incidental finding upon routine examination as patients are often visually asymptomatic with excellent visual function. Unfortunately, glaucoma is also often asymptomatic until later stages of the disease or unless there are central visual field defects.

However, SSONH structural changes are localised to the superior portion of the optic nerve, often affecting the superonasal region, which is atypical in glaucoma, where there instead may be superior and/or inferior rim thinning with development of superotemporal and/or inferotemporal RNFL defects.6,13 The presence of significant cupping or progressive thinning of the rim or RNFL and GC-IPL should increase suspicion for glaucomatous damage. Furthermore, the presence of disc pallor is atypical in glaucoma and may support a diagnosis of SSONH (although other non-glaucomatous optic neuropathies should also be excluded). Additionally, glaucoma presents with variable progressive visual field defects (e.g. nasal step or arcuate defects) depending on the pattern of structural loss, while SSONH has characteristic non-progressive inferior arcuate or altitudinal defects, often connecting to the blind spot.

OCT-A reveals significantly reduced capillary perfusion or vessel density in the superior and superonasal peripapillary region in SSONH, whereas glaucoma often shows reduced vessel density in later stages of the disease, more typically in superior/superotemporal and inferior/inferotemporal locations corresponding to RNFL defects.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

SSONH may be a lesser-known condition to optometrists compared to optic nerve hypoplasia, and thus knowledge and recognition of its presenting clinical signs is beneficial to aid in its differential diagnosis from glaucoma. However, it is important to note that a diagnosis of SSONH does not preclude patients from the development or presence of glaucoma or other optic neuropathies, and thus establishing a reliable baseline for future monitoring is essential in these patients.

*Patient name changed for anonymity.

Nicola Lee MClinOptom BSc (Vis Sci) OACAP-Gis a staff optometrist at the Centre for Eye Health (CFEH) in Sydney. She received her Master of Clinical Optometry with Excellence and Bachelor of Science (Vision Science) with Distinction from the University of New South Wales, where she also received several academic awards. Ms Lee has a passion for improving patient health and visual outcomes, with a focus on early diagnosis and management of ocular disease, patient education, and communication.

References available at mivision.com.au.

“… it is important to note that a diagnosis of SSONH does not preclude patients from the development or presence of glaucoma or other optic neuropathies”