mieyecare

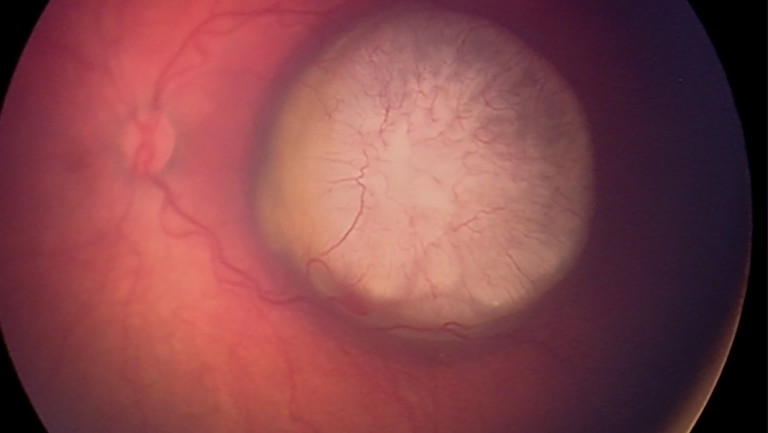

Figure 4. Retinoblastoma

tumour at posterior pole.

Could the Squint be a Sign?

Strabismus and Childhood Malignancy

September is International Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. Although in paediatric ophthalmology true primary strabismus can be readily treated to minimise associated amblyopia, improve cosmesis, and restore binocular function, on occasion strabismus will be a sign of pathology that cannot be missed.

WRITER Dr Sandra Staffieri AO

In and of itself, strabismus can be an enigma as it may appear as a fleeting occurrence in the neonatal period that resolves spontaneously with age (transient neonatal strabismus) or presents as an optical illusion (pseudo-strabismus).

Figure 1. A left) Epicanthus and B right) epicanthus showing corneal (Hirschberg) light reflex.

TRANSIENT NEONATAL STRABISMUS

As the human visual system develops, so too does the ability for the two eyes to work together to perceive a single image in the occipital cortex. Transient strabismus can be a normal finding during the first few months of life as sensorineural connections are formed as part of normal binocular development.1,2 In the early neonatal period, either esotropia or exotropia have been described, resolving spontaneously from as early as two to four weeks2 or as late as six-months of age.1

PSEUDO-STRABISMUS

The apparent presence of strabismus (pseudostrabismus) may arise due to broad epicanthic folds, naturally seen in newborns (Figures 1A and B). More common throughout infancy, it may persist up to 10 years of age.3 By obscuring the amount of nasal sclera visible to the observer, a broad epicanthus gives the illusion that esotropia is present. As the face grows and the nose becomes more prominent, the appearance of the pseudostrabismus disappears, interpreted as the child having “grown out of it”. Parents often describe observing esotropia in photographs, particularly when the infant is looking slightly to the left or right. Confirming ocular alignment with Hirschberg’s corneal light reflex negates the effect of the epicanthus; this can also be demonstrated to the parent to reassure them. Broad epicanthic folds may persist in children of Asian ethnicity or be associated with congenital syndromes (e.g., Down syndrome or blepharophimosis) or oculoplastic abnormalities (e.g., telecanthus).

That transient neonatal or pseudo-strabismus resolve with age gives rise to the impression that strabismus in young children is not significant and is readily dismissed. When a parent presents with their child having observed strabismus, fundus examination or fundal (red) reflex assessment is still required to confirm the diagnosis and that it does not represent something more sinister; even a newborn can have retinoblastoma and an infant a brain tumour.

STRAIGHTFORWARD SQUINT OR SINISTER SIGN?

Pathological strabismus can be constant or intermittent; the eye may deviate inwards, outwards, or vertically; the deviation may vary in magnitude or be described as having a sudden onset. There may be no obvious sign other than the cosmetic appearance; systemic symptoms may be manifested only when associated with a neurological aetiology (e.g., raised intracranial pressure or intracranial neoplasm).4

Primary Strabismus

The earliest diagnosis and treatment of primary strabismus in children is vital for the optimal development of vision and binocular function. With a reported prevalence of between 1–6%,5-8untreated primary strabismus can lead to significant vision impairment or disruption of binocular function and the development of stereopsis.9,10 Refractive error (hypermetropia, myopia, and anisometropia), prematurity, low birth weight, and maternal smoking have all been identified as high-risk factors for the development of strabismus.11,12 Moreover, genetic and hereditary factors predisposing to the development of strabismus continue to emerge (Figure 2).8,13,14

Figure 2. Benign/primary strabismus.

Figure 3. Left esotropia caused by posterior pole tumour.

Secondary Strabismus

Less frequently, but more significantly, strabismus can develop secondary to severe vision loss (sensory strabismus),15 systemic disease,16 or intracranial17 or intraocular pathology.18 It is this strabismus that you do not want to miss. The onset may be sudden or slow and – in the case of intracranial disease (e.g., neoplasia or raised intracranial pressure) – may be associated with additional neurologic or systemic symptoms.19

Intraocular Pathology

Retinal disease or optic nerve abnormalities that significantly impact on visual acuity can present in the first instance as strabismus and not as visual loss, particularly in the event of asymmetric disease. Similarly, intraocular pathologies that obscure central vision disrupt binocular function and are not uncommon. In describing a prospective cohort of 243 children presenting with strabismus to an ophthalmic clinic in a 12-month period, Berk and colleagues18 demonstrated that intraocular pathology is a common cause of secondary strabismus. Thirty-one (12.8%) children were diagnosed with sight-threatening conditions such as: cataract, persistent primary hyperplastic vitreous (PHPV), optic nerve hypoplasia (ONH), Coats’ disease, and life-threatening retinoblastoma (Figures 3 and 4).

In high-income countries, strabismus is the second most common presenting sign for retinoblastoma.20 A study in the United Kingdom of 133 patients newly diagnosed with retinoblastoma found 13% presented with strabismus, and 18% with strabismus and leukocoria combined.21 Of this total of 31%, exotropia (63%), and esotropia (23%), and variable strabismus (14%) were identified. Thus, the direction of the deviation does not routinely predict sensory strabismus, remaining inconsistent across reported cohorts. Esotropia has been found in 52%,18 67%,22 and 21%15 of cases compared to exotropia in 48%,18 21%,22 and 73%.15 By contrast, Hunter et al. reported an increased preponderance of exotropia associated with systemic or neurologic disease in infants under the age of one year.16

A fundus examination, or, at the very least, examination of the fundal (red) reflex – in multiple positions of gaze – is an essential part of any examination when strabismus is reported, irrespective of frequency or direction of the deviation. Prompt referral should be initiated if intraocular pathology is identified, or when in doubt of your findings or assessment.

Intracranial pathology

More challenging is the child who presents with strabismus but has other associated findings or symptoms. A careful history from the parent may identify increasing or worsening symptoms that include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, sleep disturbance, or headache. On their own they may point to myriad, potentially benign, ailments, but combined with new strabismus, worthy of further investigation. For example, a child with neurofibromatosis (NF1) may have café-au-lait spots that have gone unnoticed or dismissed as a harmless ‘birth mark’, yet their strabismus may be due to an as-yet-undiagnosed optic pathway glioma. Similarly, associated neurological signs including changes in gait or behavioural change may also be present. These should all be red flags for prompt onward referral and further investigation.

Strabismus is a relatively common finding in children with central nervous system (CNS) tumours. In Wilne et al.’s systematic review and meta-analysis of presentation of children with CNS tumours,23 strabismus was associated with brainstem tumours (19%), abnormal eye movements and strabismus (21%), and posterior fossa tumours (6% strabismus, 20% abnormal eye movements). This is in contrast to a cohort reported by Peeler et al., where 23% of patients with a posterior fossa tumour presented with strabismus.24 Due to its anatomical location, sixth cranial nerve palsies are most common25 and the resulting esotropia can be difficult to elicit in a young child, given the incomitance of the deviation between distance and near fixation.

Given raised intracranial pressure can be caused by intracranial mass lesions, there may also be evidence of papilloedema. Evaluating the optic nerve may also guide an urgent referral. Modern photographic imaging may assist in evaluating the optic nerve in a ‘busy’ child or infant.

The question of whether to pursue neuroimaging can be complicated by ready access to, and the need for, general anaesthesia in the paediatric population for the examination. Neuroimaging for new-onset strabismus can be guided by the presence of additional symptoms. As described by Choong et al.,26 abnormal imaging is frequently found in children with acute strabismus and associated signs (70.6%), however a small proportion (7.5%) with strabismus alone can also have adverse neuroimaging findings. A meticulous ophthalmic examination may reveal nystagmus or papilloedema that could further guide the indication for neuroimaging.

CHALLENGE IN PAEDIATRICS

Paediatric ophthalmology has its own specific rewards and challenges. An infant or child often does not complain of visual symptoms such as vision loss, visual field loss, or diplopia. They rely on their caregivers to notice something that is different: changes in visual behaviour, or closing one eye, or adopting a head posture to resolve diplopia. These are all signs that might be observed by the clinician that have gone unnoticed by the caregiver, thus carefully examining the child presenting with a complaint of ‘strabismus’ may elicit more than you expect to find. Further, paediatric assessments in themselves can be challenging: the tired child, the distressed child, the child that needs more time will test all your clinical skills and acumen [See further: ‘Tips and tricks for paediatric eye assessment’ by Associate Professor James Elder, mivision, February 2024].

Given strabismus may be transient or simply ‘apparent’, such that it appears to resolve over time, and that it is not always associated with systemic symptoms, it may be readily ignored, or help-seeking delayed. While strabismus is most often benign in origin, although still causing significant vision impairment with associated amblyopia, thorough medical assessment is vital to exclude the possibility that the strabismus is not secondary to significant intraocular or intracranial pathology. Early diagnosis and determination of the aetiology is critical to ensure prompt treatment and achieve the best outcome.

For every child that presents to you with strabismus for assessment and care, ask yourself, “Could this squint be a sign?”.

Dr Sandra Staffieri AO is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA) and the Manager, Retinoblastoma Service/Senior Clinical Orthoptist at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Victoria.

Dr Staffieri completed her PhD at CERA, University of Melbourne. With the aim of reducing delayed diagnosis of retinoblastoma, her study included the development and evaluation of an information pamphlet for new parents describing important early signs of eye problems in children.

References available at mivision.com.au.