mievent

Evolving the Profession Optometry Virtually Connected

Professor Andrew Turpin and Cassandra Haines

WRITERS Sarah Case and Chelsea Lane

Optometry Virtually Connected 2023, presented by Optometry Australia, was an exploration into the evolving landscape of our profession and the world in which we practise. Presented online, this was a fitting setting in which to explore the role of artificial intelligence (AI) and how changing climate and lifestyles are affecting our eyes and behaviour.

Despite its online delivery, the concept of connectedness was strong. The question panel was well used, the conversation between hosts and lecturers was easy, and strong themes of mental health and cultural competence were reinforced throughout, as optometrists Sarah Case and Chelsea Lane report.

Optometry Virtually Connected kicked off with movement and mindfulness at 8:30am. This session was recorded so that we could re-watch it and repeat the stretches on Monday before work, for which I’m sure many were grateful. The session was chair-based so entirely appropriate for optometrists, as we sit in a dark room, on an office chair, slumping forward all day. What a fun start to a conference!

After a Welcome to Country, we got straight into AI, data, and eye care. Professor Andrew Turpin led us through an overview of AI, touching on sociology and philosophy with a healthy dose of dry humour scattered throughout. He discussed the shortcomings of AI as it currently stands, noting that most optometric AI currently operates as surface level ‘machine learning’, as well as its exciting future potential.

We were introduced to the ‘white box’ of machine learning, where we see the input, see the process, and understand the output, as distinct from the ‘black box’ of deeper learning where the reasoning process is hidden. This ‘black box’ is more similar to the human brain, which is what ‘deep learning’ machines try to emulate. Deep learning can alter and add its own input layers, teaching itself.

Prof Turpin identified the main issue with optometric AI: It is only as good as the training data used, which to date, has been problematic. The features need to be (but too often are not) input articulately and without bias. Early clinical trials suggest AI is excellent at detecting disease in trials where the fundus quality is excellent, and homogenised. In practice, however, photos are rarely up to the same standard. Data codifies the past – no reasoning or deductions, no concept of truth or lie – just pattern searching the past based on input training data.

Prof Turpin gave us all hope that as yet, AI won’t be taking our jobs but may be used as a tool for our practices.

TARGETED THERAPEUTICS

It was particularly interesting to attend Varny Ganesalingam’s presentation on ‘Targeted topical and oral therapeutics’. Ms Ganesalingam introduced us to the dry eye specialty clinic established within the Australian College of Optometry (ACO) to address the unfortunate reality of patients being undertreated with their “bit of dry eye”, thus suffering secondary ocular inflammation, ocular damage, and loss of function and vitality. Deliberate focus on this disease enables individualised and evidence-based management strategies for early intervention to improve quality of life. Tetracycline derivatives for dry eyes have a dual benefit, acting as both an antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory. We learnt that oral azithromycin appears to be more beneficial for patients suffering lipid deficient dry eye than doxycycline. It showed greater efficiency at treating meibomian gland dysfunction, provided greater reduction in symptoms, fewer adverse effects, and an easier course of treatment (a four-day course, starting with 500mg then 250mg daily for three to four days).

We revised ocular surface inflammation and different oral and topical treatments for this, including oral antibiotics (dual anti-inflammatory action), corticosteroids, and immunomodulators. The different types of ciclosporin medication were explained, with Ikervis used 0.1% once daily at night compared with Cequa, 0.09% twice daily. Both are preservative free and subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme for patients who meet the criteria. Practically, neither of these provide an immediate benefit, so patients should be counselled on a few weeks’ wait and be prepared for a six to 12-month course of treatment.

Finally, we covered off some of the less common treatments, such as tacrolimus, Lifitegrast/ Xiidra and autologous serum eye drops. It’s an exciting area of optometry and it’s hoped that, one day, we can do more for these patients with orals. For now, facilitating management and directing treatment is an important function for our profession.

CLIMATE CHANGE

To finish off day one, Suki Jaiswal discussed ‘Climate change and the ocular surface’, presenting sobering statistics regarding the state of our corneas leading into a warmer world.

Ms Jaiswal is currently completing her PhD on the impact of bushfire smoke on the ocular surface. Her presentation was broken down into the following main parameters and their impact on the ocular surface:

• Increasing UV, increasing neoplasia, and climatic droplet keratopathy.

• Allergens possibly increasing allergic conjunctivitis.

• Heatwaves possibly increasing dry eye, possibly counteracted by increasing humidity.

• Disease increasing, with microbes flourishing in warmer weather and vector borne disease increasing systemic illness via ocular sequalae.

• Disaster such as drought, storm, flood, and bushfire affecting health care access (have telehealth and stocks prepared). Bushfires can also release toxic components that may be carcinogenic and irritating to the ocular surface.

• Air pollution increasing eyelid disease, conjunctivitis, and risk of inflammatory events.

We learnt how to recommend and prescribe protective devices for these patients as we head into our new climate.

ANTICANCER DRUGS

With one in four Australians being affected by cancer, a day two discussion on ‘How anticancer drugs affect the eye’, by Dr Jeremy Chiang, was well attended by those wanting to know how to best support these patients with their ocular complications. Dr Chiang completed his PhD on the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on the eye, and shared first-hand experience and case studies to create an engaging discussion. He explained that the eye has a fast cell turnover rate and similar molecular targets to those addressed by cancer medications and can therefore be a common area of side effects. Dr Chiang went through each class of anti-cancer drug and their possible ocular effects, starting with:

• Cytotoxic chemotherapy induces cell death to reduce tumour load. Different drugs have a range of possible adverse effects, such as vincristine and ptosis, 5-fluoroacil and docetaxel and lacrimal drainage obstruction, taxanes and cystoid macula oedema, and gemcitabine and retinal hemorrhages/ vascular occlusions.

• Hormone therapies may induce crystalline keratopathy and retinopathy with cystoid macular oedema secondary to tamoxifen use or meibomian gland dysfunction secondary to aromatase inhibitors.

• Targeted therapies, such as small molecule inhibitors (‘ib’ suffix) can cause corneal defects, vortex keratopathy, periocular oedema, retinopathy and uveitis. Biological agents (‘mab’ suffix) carry a higher likelihood of ocular inflammatory events.

Finally, Dr Chiang wanted all listeners to ensure their cancer therapy patients aren’t glossed over. Visual disturbance in cancer patients isn’t just ‘chemo fog’, the medications they take can disrupt the eye.

CONTACT LENS COMPLIANCE

Associate Professor Nicole Carnt presented a lecture on improving compliance with contact lens wearers. With 80% of contact lens wearers being non-compliant, ideas as to how we can get through to these patients are much needed. We started with a refresher on how to differentiate infection from inflammation and the likelihood of occurrence based on risk factors. Ninety per cent of microbial keratitis (MK) is secondary to bacterial infection. ‘Ideal’ contact lens care takes 47 steps, and the rate of compliance with all of these is only 0.3%, which creates high risk levels for many contact lens wearers.

Assoc Prof Carnt broke her presentation into four main areas:

• Susceptibility of patient: elevated with increased contact lens wear time (>6 days a week or extended wear), those who purchase online, occasional overnight use (removing this alone, drops MK by 43%), and poor hygiene. Holidays increase susceptibility with poorer hygiene often practised. Travel to warmer/more humid areas also increases the likelihood of severe keratitis.

• Severity of infection: risk of vision impairment secondary to keratitis is linked strongly with tap water (e.g., showering in lenses). Written instructions and a sticker on the case denoting ‘NO tap water’ increases adherence. Case hygiene and replacement reduces bacterial load by 62%, and daily disposables are four times less risky than reusables.

• Benefits of compliance: reduces the burden on our healthcare system and is of great benefit to the community, the individual, the practitioner, and the practice.

• Barriers to compliance: unconscious (understanding/communication), conscious (time, inconvenience, other priorities, behaviours reinforced as adverse events), control (motivation, personality), risk taker.

Assoc Prof Carnt also provided some useful tips and tricks:

• Assume noncompliance to obtain an accurate history, e.g. ask “how often do you sleep in lenses?” instead of “do you sleep in lenses?”.

• Use psychological tools to encourage patients to comply, e.g., “if you… then you can wear contacts for many years” shows the advantage of compliance. Loss aversion should be reserved for non-compliant wearers.

• Reinforce social norms, e.g., note that “95% of lens wearers wash hands before touching lenses”.

MYOPIA MANAGEMENT

Stream two on day one focussed on one of the major areas of interest in optometry, myopia. Dr Emily Pieterse provided an outstanding summary of recent myopia research in her lecture titled ‘Staying in control of progressing myopia’. Her take home message was to initiate myopia control treatment as soon as possible. “Starting treatment early gives maximum effect, there is no better time to start myopia control than when you first identify myopia in a patient.”

Outlining the risk factors for myopia (non-modifiable: age, ethnicity, geography, and parental history; and modifiable: near work, outdoor time, and living in an urban environment), Dr Pieterse said age was singled out as the greatest predictor of future myopia. Optometrists have an important role in educating patients about modifiable risk factors, such as near work and outdoor time; patients should be encouraged to have a five-minute break from near work every 30 minutes, have a working distance >30cm and try to spend at least two hours outdoors per day. Dr Pieterse raised the point that even doing near work outdoors is more beneficial than near work indoors.

We are lucky to have an arsenal of high-level treatment options for myopia control, many of which are relatively accessible, requiring no specialised equipment. High level options (i.e., low dose atropine, orthokeratology, MiSight, Stellest, and Miyosmart lenses) can all slow myopia progression by 40–60%. Recent advances in spectacle options means that we have highly effective options to curtail myopia progression – even for very young children who may not yet be suitable for atropine or contact lenses. This talk highlighted how myopia control has become an accessible and important aspect of mainstream optometry.

HIGH MYOPIA

In the afternoon, Dr Weng Chan provided some perspective about our efforts to reduce high (defined as >-6.00DS or axial length >26.5mm) and pathological myopia (defined as >-8.00DS or axial length >32.5mm) in our patients. Dr Chan’s fascinating and sobering lecture reminded us about the pathologies associated with high axial length, and the inherent difficulties in the surgical treatment of these complications. Pathological myopia affects 0.5–3% of the population and signs include lacquer cracks, tessellated fundus, and choroidal neovascularisation. Dr Chan emphasised the point that myopia is not just refractive error; there can be significant comorbidities in elongated eyes, hence optometrists can play an important role in preventing our patients from reaching these axial lengths in the first place.

Among the many peripheral retinal degenerations associated with high myopia, Dr Chan outlined the pathologies of most urgent need of assessment by a vitreoretinal surgeon, which were areas of evidence of subretinal fluid, horseshoe tears, and any areas of vitreoretinal traction. Symptomatic horseshoe tears have a 50% chance of progressing into a retinal detachment. Among other pathologies, such as lattice degeneration, risk of progression to retinal detachment is low and can be managed with non-urgent ophthalmology referral and/or optometry review.

Surgeries to repair such complications are made inherently more difficult by the elongation of the eye. As well as making surgeries more difficult, routine scans such as optical coherence tomography and biometry have reduced accuracy in highly myopic eyes. This lecture provided a fascinating look at high myopia from the perspective of a vitreoretinal surgeon.

PUBLIC HEALTH AND INDIGENOUS EYE CARE

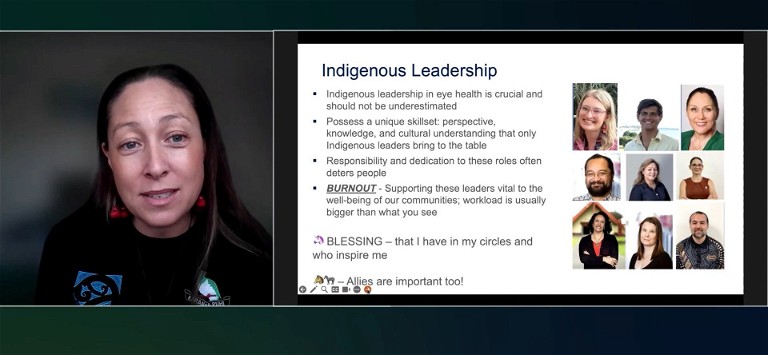

Day two started with an important plenary lecture from Professor Sharon Bentley, Professor Isabelle Jalbert, Professor Fiona Stapleton and Renata Watene highlighting some of the research articles that featured recently in the special edition of Clinical and Experimental Optometry. This special edition was based around public health and Indigenous eye health with 16 articles falling into three themes; Indigenous eye care, models of eye care, and children’s vision. The plenary presentation highlighted a few key articles under each theme.

The ability of optometrists to provide culturally safe practice to all our patients is so vital that it is incorporated into the Ahpra code of conduct in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand’s Standards of cultural competence and cultural safety for optometrists and dispensing clinicians. According to Ahpra, cultural safety involves ongoing critical reflection on practitioner skills, attitudes, practising behaviours, and power differentials; delivering safe, accessible, and responsive health care; and delivering health care that is free of racism.

The Indigenous population is underrepresented by clinicians in both countries, with only 0.2% of Australian optometrists identifying as Indigenous Australians and only 1.6% in Aotearoa New Zealand as Māori. The Optometry Council of Australia and New Zealand (OCANZ) has now set a requirement for optometry schools in Australia and New Zealand to ensure that their graduates are able to practise in a culturally safe way.

It was exciting to hear about the work being done to make eye care more accessible. The editors of Clinical and Experimental Optometry reported that while they were extremely encouraged by the response to the special edition, more work needs to be done.

SYSTEMIC OCULAR DISEASE

The theme of stream two on Sunday was ‘Systemic’ and two lectures highlighted multifaceted aspects of clinical optometry and eye care provision. Dr Josephine Richard’s lecture, ‘Systemic auto-immune disease and eye health: Not quite what you expected?’ exposed optometrists to the complexities of auto-immune and autoinflammatory diseases and how they can be expressed in the eye.

Pure autoinflammation stems from activation of the innate immune response without an apparent cause, and pure autoimmunity stems from T and B cells attacking healthy tissues, which can be caused by a variety of factors. Hence many health conditions commonly seen in optometry, such as lupus, types 1 and 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and acne-rosacea, lie along an inflammatory spectrum that combines elements of both the auto-inflammatory and auto-immune responses.

Dry eye disease is a common presentation stemming from conditions on the inflammatory spectrum, with a combined mechanism present in most dry eye cases. However, it is important to distinguish between evaporative (often caused by rosacea-blepharitis) and tear deficient (more likely to be auto-immune), because steroids are contra-indicated in cases of evaporative dry eye and can exacerbate the problem.

Microbes can be harmful by causing infection and triggering auto-immune and autoinflammatory disease. However, they can also be helpful by dampening inflammation and fighting off other bad microbes. Hence optometrists need to be careful not to wipe out good bacteria by unnecessarily prescribing antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, which can destroy the natural surface flora for up to six months. When viewing a red eye with pus and mucous, don’t assume that antibiotics are needed to treat infection as these presentations can also be caused by autoimmune and autoinflammatory responses.

NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Dr Maryanne Coleman gave a practical and useful lecture regarding considerations for optometrists in assessing and managing the ocular health of patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia and Parkinson’s. Dementia is the most common neurodegenerative condition in Australia and is not considered a part of natural ageing. Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative disease and affects 1% of people aged 60 and above. Key hallmarks are tremor, rigidity, loss of balance, co-ordination, and initiation of movements; all of which are impaired due to loss of cells in the brain in the areas that control movement.

Being able to see clearly is of utmost importance to patients with dementia and Parkinson’s, as it allows them to continue to participate in activities that are important to them. There is also evidence that vision impairment itself is a risk factor for cognitive decline and may soon be listed as a modifiable risk factor for dementia. Unfortunately, despite the benefits that optometrists can provide to this cohort, patients with neurodegenerative conditions experience access inequalities and are less likely to have had an optometry visit each year.

When conducting an exam for a patient with dementia or Parkinson’s it is important to allow the carer to be present, establish preferred communication methods (e.g., write points down or tell the carer), be patient, and demonstrate what is required. Cognitive fatigue can make participating in eye exams hard, so practitioners should be willing to use objective measures.

With an ageing population it is important that optometrists understand these common conditions and how best they can care for their patients.

CONCLUSION

Optometry Virtually Connected covered a range of novel and innovative content over two days. The lectures were well received by the hundreds of optometrists tuning in and prepared us for the expanding scope of our industry and the changing eyes of patients we are likely to manage.

Chelsea Lane is an optometrist practising in Geelong and Colac. She completed the Doctor of Optometry through the University of Melbourne in 2018 and has since completed an Advanced Certificate of Children's Vision in 2021. She is particularly interested in health promotion, with experience as a committee member for the Optometry Australia ECOVSA and a Fred Hollows Outreach program participant.

Sarah Case graduated from the Doctor of Optometry at The University of Melbourne in 2017. Ms Case is currently practising with OPSM in metropolitan Melbourne but also enjoys practising rurally, providing rural relief stints. She completed the Australian College of Optometry’s Advanced Certificate of Children's Vision in 2020 and is currently on the State Advisory Committee for Victoria/South Australia.