mieyecare

WRITER Jillian Campbell

Causes & Management

Lipid Keratopathy in Scleral Lens Wearers

Scleral lenses have become increasingly popular in recent years as a means of correcting vision and managing various eye conditions. However, like other forms of contact lens wear, scleral lens use comes with its own set of potential complications, including lipid keratopathy (LK).

In this article, optometrist Jillian Campbell explores the causes, diagnosis, and treatment options for LK, and presents two intriguing case studies.

Lipid keratopathy (LK), is a condition characterised by the deposition of abnormal lipids in the cornea. 1 Patients with advanced corneal ectasia, particularly those reliant on scleral lenses, face an enhanced risk of developing LK. Prolonged scleral lens usage can lead to inflammation and/or hypoxia, with subsequent development of neovascularisation, creating an environment conducive to lipid keratopathy.

While LK can arise from various factors, this article focusses on its occurrence in individuals who wear scleral lenses.

IDENTIFYING LIPID KERATOPATHY

In most cases, LK develops following corneal inflammation and neovascularisation. 2 The invasion of blood vessels and lymphatic channels into the avascular cornea creates pathways through which blood constituents gain access to the stroma. The lipid deposits can occur at various depths but are commonly found at the endpoints or along the routes of these vascular changes.

LK is characterised by distinct clinical signs, including the presence of dense cholesterol crystals in yellow, white, or cream colours, arranged in a fan-like pattern in the corneal stroma. These crystals are often observed surrounding blood vessels. During active keratitis, a plaque with a fanshaped appearance is commonly observed. However, in cases where there is diffuse neovascularisation (NV) in the cornea, one may observe diffuse lipid deposits rather than localised plaques. Disease progression can lead to an increase in neovascularisation and subsequent lipid deposition. As this pattern continues, it may begin to impact visual acuity due to opacity. Additionally, the development of vessels and plaques can contribute to the occurrence of irregular astigmatism.1

TYPES OF LIPID KERATOPATHY

Primary Lipid Keratopathy Primary lipid keratopathy is an extremely rare form of the condition that occurs without any known systemic or corneal disorder. 2These cases typically affect both eyes and involve a gradual, progressive deposition of lipid in the stroma, sometimes causing a bulging effect towards the anterior chamber. Histochemical analysis of affected eyes has revealed the presence of neutral fats, free fatty acids, phospholipids, and cholesterol.1 Interestingly, primary LK is not associated with abnormal serum lipid profiles and its underlying cause remains largely unknown.1 Idiopathic LK typically presents bilaterally without previous corneal neovascularisation or serum lipid abnormalities.

Secondary Lipid Keratopathy The secondary form of lipid keratopathy, which is frequently encountered in clinical practice, is the type presented in this article. Two case reports are described in which this form of lipid keratopathy presented in patients wearing scleral lenses. Secondary LK more often arises from conditions such as infectious keratitis, Cogan’s syndrome, corneal trauma, corneal incisional surgery, interstitial keratitis, or other types of corneal inflammation. It can also be seen in noninflammatory conditions such as Terrien’s marginal degeneration. Corneal ulcers and herpetic keratitis are frequently observed as precursors to LK.

DIAGNOSIS

To ensure an accurate diagnosis of LK, it is crucial to consider other similar conditions. While LK may share some similarities with corneal arcus, it typically exhibits a denser appearance and can present as circular deposits near blood vessels. On the contrary, corneal arcus is the most prevalent form of ocular lipid deposition, distinguished by lipid accumulation in the perilimbal stroma.

It initially appears superior and inferior, gradually progressing circumferentially to form a band about 1mm wide, with a clear zone separating it from the limbus.3,4 While corneal arcus is commonly observed in the elderly population, in younger individuals it may be linked to dyslipidaemia.

Another potential consideration for differential diagnosis is Schnyder corneal dystrophy, an uncommon hereditary stromal dystrophy characterised by progressive bilateral corneal opacification caused by abnormal cholesterol and phospholipid deposition in the cornea without associated neovascularisation.2

“ LK is characterised by distinct clinical signs, including the presence of dense cholesterol crystals in yellow, white, or cream colours, arranged in a fan-like pattern in the corneal stroma ”

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment options for LK vary depending on the underlying cause and the severity of the condition. The first step should involve addressing the root cause, such as reducing hypoxic conditions including excessive contact lens wear if applicable. Consider the lens modality the patient is wearing and explore the availability of better oxygentransmissible materials.

Corticosteroids are often prescribed due to their anti-inflammatory properties. However, their effectiveness may be limited when neovascularisation is non-inflammatory in nature. While corticosteroids can suppress the activity of inflammatory cells and mediators that release pro-angiogenic growth factors, they do not directly inhibit angiogenesis.1 When managing inflammation in lipid keratopathy, the choice of steroid should be influenced by its ability to penetrate ocular tissues since most of the lipids and neovascular changes occur in the stroma in this condition. Fluorometholone alcohol 0.1% (FML) may not be the most suitable option due to limited corneal penetration.

In cases of moderate inflammation, combining fluorometholone with an acetate base (Flarex) provides improved corneal penetration, making it a more effective choice. However, prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte) remains the optimal choice for severe ocular inflammation in lipid keratopathy, displaying the highest level of anti-inflammatory efficiency among topical steroids. The selection between Flarex and Pred Forte depends on the severity of the lipid condition and weighing this up against the potential steroid side effects.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves using a photosensitising agent and light to selectively destroy abnormal blood vessels, thus reducing neovascularisation.1 Another treatment option is anti-VEGF therapy, which uses antibodies that specifically target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein crucial for the development of new blood vessels. By inhibiting VEGF, this therapy aids in suppressing neovascularisation. However, it is important to note that anti-VEGF therapy can lead to complications, such as corneal melt and may not be highly effective.5

Argon laser treatment uses an argon laser to selectively destroy abnormal blood vessels in the cornea, aiming to reduce neovascularisation and improve the overall condition of the cornea.5 Another technique, needlepoint cautery, involves applying controlled heat to abnormal blood vessels using a fine needlepoint. The heat cauterises the vessels, leading to their closure and subsequent reduction in neovascularisation.2

Penetrating keratoplasty is considered a last resort and may be necessary in severe cases of LK that do not respond to other treatments.

CASE STUDY ONE

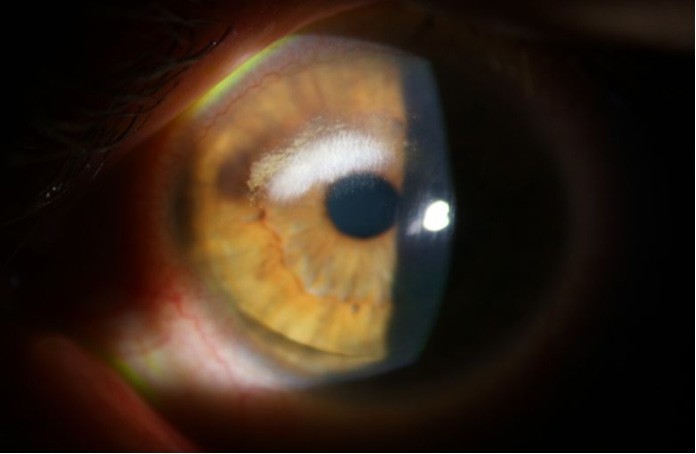

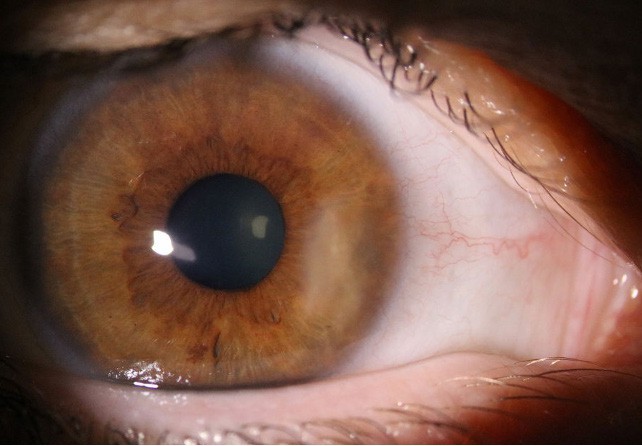

A 36-year-old male patient with a history of post-LASIK ectasia and long-term contact lens use presented with very specific symptoms of nocturnal clouding of his superior paracentral vision. He had previously used rigid corneal lenses unsuccessfully and had been a very happy scleral lens wearer for the past two years. This visual finding corresponded with the clinical appearance of lipid keratopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Slit lamp image of the anterior segment of the left eye from case study one at presentation, demonstrating a superior arcuate area of LK with neovascularisation. The LK is encroaching on the superior aspect of the pupil.

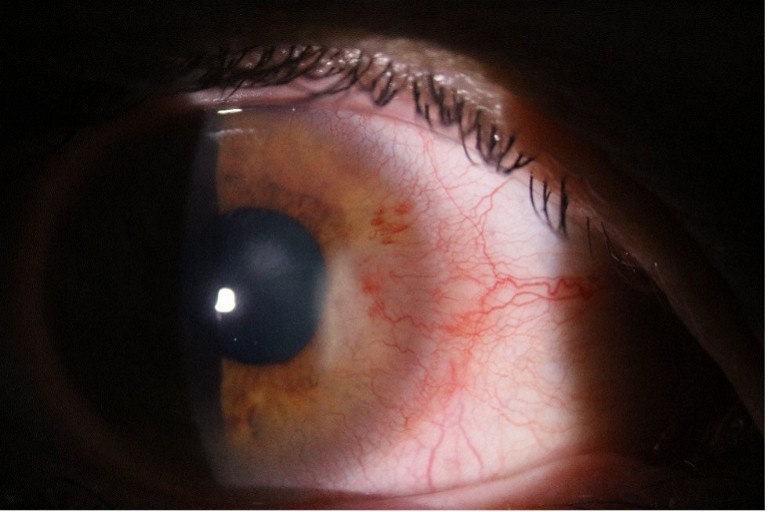

Figure 2. Slit lamp image of the anterior segment of case study two at presentation, displaying marked corneal neovascularisation with an adjacent, developing fan of lipid deposition.

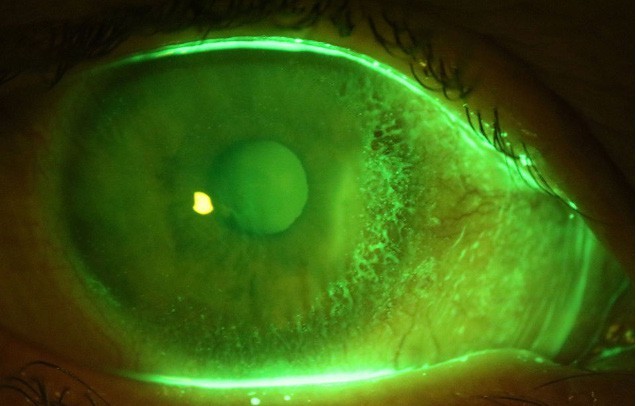

Figure 3. Fluorescein enhanced slit lamp image of the anterior segment of case study two showing staining around the nasal limbus, indicating elevation and irregularity of this area due to growth of new vessels and lipid deposition.

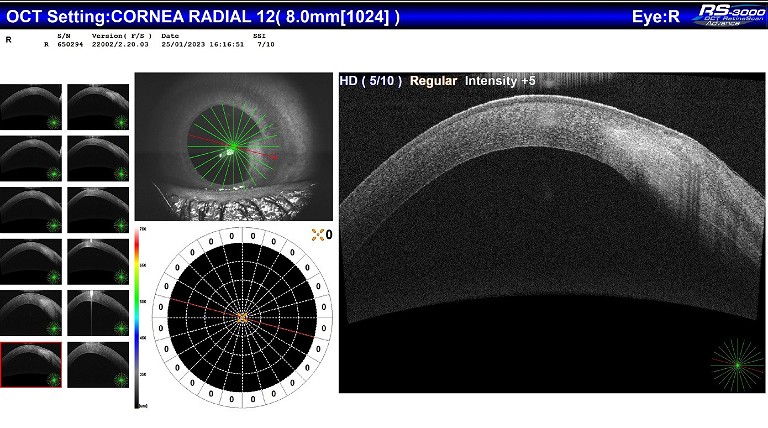

Figure 4. Anterior segment OCT image of case study two at presentation, showing thickening and opacification of the area of LK. Note that the cornea bows outwards towards the tear film and also inwards towards the anterior chamber.

No signs of inflammatory cells or flare were observed in his otherwise stable eye. Additionally, he had meibomian gland dysfunction and corneal neovascularisation, predominantly at the superior limbus.

The patient disclosed that he was having sleep disturbances due to a complicated family situation. Over the past few months, he had been wearing his scleral lenses for extended periods, totalling approximately 22 hours a day. Counselling was provided to the patient regarding the importance of reducing lens wear time. Furthermore, he was informed that failure to comply might result in the need to return to corneal rigid lenses, which he was keen to avoid. Additionally, the patient was prescribed Pred Forte, to be administered four times daily for a duration of one month.

Upon follow-up, the patient did not show any improvement in the lipid keratopathy or corneal neovascularisation. As a result, the patient was referred for electrolysis needle cauterisation as a targeted intervention to address the neovascularisation and reduce the lipid deposits.

“ Penetrating keratoplasty is considered a last resort and may be necessary in severe cases of LK that do not respond to other treatments ”

CASE STUDY TWO

A 42-year-old patient with keratoconus, with a history of long-term contact lens wear, presented with a red right eye and hazy vision. She had been wearing scleral lenses for the past four years without any major issues. She complained of eye fatigue but denied experiencing any pain. Upon anterior eye examination, a raised translucent lesion was observed on the nasal cornea (Figures 2 and 3), accompanied by conjunctival vessels and superficial blot haemorrhages. Anterior segment ocular coherence tomography revealed increased corneal thickness in that area, but no ulceration or epithelial defect was detected (Figure 4). The patient’s ophthalmologist diagnosed her with interstitial keratitis. She was prescribed Flarex four times daily and given Valtrex cover for one week, as herpetic inflammation was suspected as the underlying cause. However, after extensive blood testing, the diagnosis was revised to lipid keratopathy secondary to scleral lens wear. The patient’s scleral lens fit was reevaluated. There was no history of limbal insult, the scleral lenses were made from Acuity 200 material (a hyper-Dk material), and the physical fit demonstrated adequate corneal clearance. She had recently welcomed a baby into her family, and her daily wear time in scleral lenses had increased because of this. No further treatment was deemed necessary as the LK was not located near the visual axis and demonstrated no evidence of progression. Interestingly, comprehensive blood tests revealed a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) with a titre of 640, although no apparent autoimmune conditions were detected.

Figure 5. Slit lamp photograph of the anterior segment of case study two at one month post initial presentation, showing improvement in neovascularisation and less intensity to the opacity due to lipid deposition now that inflammation is under control with steroid treatment.

It is noteworthy to mention that in reviewing the patient’s history, she had worn SoftPerm lenses for many years prior to the release of our newer hyper-oxygen permeable materials. SoftPerm lenses were low Dk hybrid contact lenses and were associated with a high incidence of corneal neovascularisation.6The patient had no history of corneal neovascularisation while using SoftPerm contact lenses visible on slit lamp. However, it may have been that there was stromal vascularisation that was not easily visible. According to a very small number of cases published with histopathological studies, there is usually a presence of vascularisation in the corneal stroma in secondary LK cases.7

CONCLUSION

Scleral lens patients are at risk for lipid keratopathy. The risk is particularly high for those with advanced corneal disease who rely heavily on contact lens wear to function and for those with neovascular changes present. The risk is mitigated by using highly oxygen permeable contact lens materials and ensuring appropriate lens fitting characteristics.

It is important to note that this article does not attribute blame solely to scleral lenses. Both patients outlined in this case series had a history of prior lens wear and surgery, indicating the complexity of their cases. It is likely that the prolonged hypoxia resulting from lens wear over a significant period contributed to neovascularisation, eventually leading to lipid keratopathy. Understanding this heightened risk is vital for early detection and proactive management.

By closely monitoring these patients, implementing appropriate interventions, and promoting responsible lens wear, we can mitigate the risk of lipid keratopathy and its potential impact on vision. This will also help prevent corneal topographical changes and deterioration of vision due to the changes in the cornea caused by lipid development. Continued research and awareness are necessary to improve our understanding of this condition and optimise care for scleral lens wearers.

“ By closely monitoring these patients, implementing appropriate interventions, and promoting responsible lens wear, we can mitigate the risk of lipid keratopathy and its potential impact on vision ”

Jillian Campbell BVisSc MOptom is the Director of Richard Lindsay and Associates in Balwyn North, Victoria.

References

1. Hall, M., Moshirfar, M., Amin-Javaheri, A., et al., (2020). Lipid Keratopathy: A review of pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and management. Ophthalmol Ther, Dec;9(4):833–852.

2. Knez, N., Walkenhorst, M., Haeri, M., (2023). Lipid keratopathy: Histopathology, major differential diagnoses and the importance of clinical correlation, Diagnostics (Basel), May 4;13(9):1628.

3 Alfonso, E., Arrellanes, L., Boruchoff, S., et al., (1988) Idiopathic bilateral lipid keratopathy. Br J Ophthalmol, 72(5):338–43

4. Barchiesi, B.J., Eckel, R.H., Ellis, P.P., The cornea and disorders of lipid metabolism. Surv Ophthalmol. 1991 Jul-Aug;36(1):1-22. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(91)90205-t. Erratum in: Surv Ophthalmol 1992 Jan-Feb;36(4):324.

5. Reddy, C., Stock, E., Mendelsohn, A., et al., (1987). Pathogensesis of experimental lipid keratopathy: cornea and plasma lipids. Invest Ophthalmol, Sep;28(9):1492–6.

6. Chung, C.W., Santim, R., Heng, W.J., Cohen, E.J., Use of SoftPerm contact lenses when rigid gas permeable lenses fail. CLAO J. 2001 Oct;27(4):202-8.

7. Ghanem, R.C., Ghanem, V.C., Victor, G., Alves, M.R., Bilateral progressive idiopathic annular lipid keratopathy. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2012;2012:731413. doi: 10.1155/2012/731413.