miophthalmology

Surgical Vision Correction:

From Laser to Lenses

WRITER Dr Alison Chiu

Today’s patients require more than visual correction – they need refractive planning that protects their long-term potential. In this article, Dr Alison Chiu outlines the current suite of surgical refractive options that move beyond the ‘quick fix’ to prioritise durability and adaptability.

Refraction may be the most fundamental of clinical skills, yet translating this into permanent surgical correction remains a nuanced challenge. As a high-volume refractive surgeon, I’ve had the privilege to perform many tens of thousands of procedures across the spectrum of vision correction – from laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE), and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) to lens-based procedures such as phakic IOL implantation (ICL surgery), refractive lens exchange, and cataract surgeries utilising monofocal, extended depth of focus (EDOF) and multifocal (MF IOL) intraocular lenses.

While laser-based options like LASIK are well-established and well-known for correcting low-to-moderate myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism, the refractive landscape has evolved. Increasingly, we are seeing younger patients present with higher degrees of myopia at earlier ages – a trend driven by lifestyle, environmental, and genetic factors contributing to what is now widely recognised as a global myopia epidemic. These patients not only require precise correction today but also deserve long-term strategies that preserve the integrity and potential of their eyes for the future. ICL surgery is one such strategy to address this.

At the same time, we are entering a new era of presbyopes. These are not the patients of decades past who reluctantly accepted reading glasses as an inevitable part of ageing. Today’s presbyopes are active, engaged, and imageconscious individuals – often in their 40s and 50s – who view reading glasses as intrusive and incompatible with their professional, personal, and digital lifestyles. They seek clarity not just of sight, but of identity. Meeting their expectations requires refractive solutions that go beyond convention – approaches that restore function without compromise. For presbyopia correction, our surgical refractive options include laser-based corneal procedures, ICL-based procedures, and more definitive refractive lens exchange procedures.

Fortunately, our expanding IOL toolkit now includes low-add EDOFs, multifocal IOLs, multifocal hybrid IOLs, and AI-optimised optics.1 We are entering an era where the boundaries between phakic and pseudophakic refractive surgery will continue to blur.

In this article, I aim to outline the current suite of surgical refractive options, with a focus on meeting the demands of increasingly complex patient expectations. I emphasise where phakic intraocular lenses (IOLs) – the implantable collamer lens (ICL) and ICL Viva – fit into our decision-making framework. Today’s patients require more than just immediate visual correction – they need refractive planning that protects their long-term potential, and we must prioritise the robustness and flexibility of the solutions we offer. From corneal to lens-based surgery, and from today’s optics to tomorrow’s AI-guided lenses, this is the evolving pathway to pure sight.

LASER VISION CORRECTION: STILL FOUNDATIONAL, NOT ALWAYS FIRST-LINE

Laser vision correction – whether via LASIK, SMILE, or PRK – remains the best-known form of refractive surgery, both among clinicians and patients. Each modality offers proven outcomes with high rates of satisfaction and stability when performed in the right patient. I offer all three platforms in my surgical practice, including more recently, PresbyLASIK (such as Presbyond and PresbyMax) for presbyopic patients in selected cases.

However, it is important to recognise that the relative technical ease of performing laser refractive surgery (especially PRK) belies the complexity of selecting the right candidate. Success hinges on experience, pattern recognition, and surgical maturity – skills that cannot be entirely algorithmically replaced.

I was fortunate to train under the late Dr Con Moshegov, a pioneer in Australian refractive surgery, whose influence remains foundational to my practice philosophy. Our specialist training does not equip us well in refractive surgery and the value of fellowship training, followed by a decade of experience with senior mentorship at the outset, cannot be underestimated in caring expertly for our patients and their outcomes.

“the value of fellowship training, followed by a decade of experience with senior mentorship at the outset cannot be underestimated in caring expertly for our patients and their outcomes”

Advancements in diagnostics – such as tomographic elevation, epithelial mapping, and biomechanics – have improved our assessments but also introduced a paradox: increased reliance on automated analysis can sometimes lead to more permissive surgical decisions. Dr Aanchal Gupta has explored this tension superbly in her article on ectasia risk assessment published in mivision.2 As clinicians, we must remain aware that more data does not automatically equate to better decisions. The judgement remains human, backed with solid experience.

While laser vision correction remains a cornerstone of refractive surgery, offering excellent outcomes in well-selected patients, younger corneas present distinct challenges.3 As the myopia epidemic accelerates, and more young adults present with progressive or high myopia, the limitations of corneal ablation become increasingly apparent.

For younger adults, particularly those with moderate-to-high myopia or early axial length progression, laser vision correction may not be the optimal first-line strategy. The cornea, still potentially changing, may not support stable long-term correction. Unlike phakic IOL options, laser ablation is irreversible and sacrifices corneal tissue. It also alters the eye’s natural aberration profile and disrupts the relationship between the anterior and posterior corneal surfaces – an important consideration for future IOL calculations, necessary when inevitable cataract formation takes hold. In an era where premium presbyopia-correcting IOLs (used during refractive lens exchange and cataract surgery) require low-aberration optics for optimal performance, these corneal changes can significantly reduce future surgical options and calculation accuracy. This is an important consideration for the patient seeking spectacle independence with laser vision correction in the first place.

In this context, phakic IOLs offer a compelling alternative. With long-term safety data and a fully reversible, cornea-sparing profile, the ICL is increasingly being considered not as a fallback but as a primary modality for the younger, highexpectation patient. Its compatibility with future IOL technologies reinforces its strategic value in long-term refractive planning.

In these younger cohorts, we must think more broadly. Fortunately, we have tools with longterm safety data that allow for cornea-sparing correction – offering reversibility, stability, and compatibility with future lenses. This brings us to the evolving role of the ICL.

While laser procedures may not be suitable for every patient – particularly those with high myopia – they continue to offer outstanding outcomes in well-selected individuals, especially those with stable refractions and healthy corneas. It’s important to recognise that dry eye is on the rise, and this too must be weighed with corneal laser treatment, but laser remains an essential part of the refractive toolbox.

REFRACTIVE STRATEGY IN THE MYOPIC YOUNG ADULT

The Visian implantable collamer lens (ICL) remains the only phakic intraocular lens currently approved by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and by the New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (Medsafe) for the correction of myopia in phakic eyes. Accordingly, this article refers exclusively to the Visian ICL when discussing phakic lens-based vision correction.

“As clinicians, we must remain aware that more data does not automatically equate to better decisions”

Among younger adults, especially those with moderate-to-high myopia who have thinner corneas or longer visual life expectancies, the ICL should not be considered a backup procedure for patients who ‘fail’ laser screening. Instead, it is increasingly positioned as a first-line option in its own right – and for good reason.

Compared with corneal laser surgery, ICL implantation is additive, reversible, and optically neutral at the corneal level. It does not affect ocular surface integrity or biomechanical stability, and it preserves corneal architecture for future IOL calculations. In a landmark Cochrane Review, Barsam and Allan4 demonstrated that phakic IOLs produced superior safety outcomes, better contrast sensitivity, and greater patient satisfaction compared to corneal excimer laser for myopia over -6.00D. While uncorrected acuity outcomes were comparable, phakic IOLs showed fewer adverse events and less loss of best-corrected vision. In my experience of performing ICL surgery for over a decade, the claims of ‘higher-definition vision’ with ICL surgery are well-founded – particularly when meticulous surgical technique is paired with an optimal refractive outcome.

Importantly, the indications for ICL are evolving. Recent data, particularly from highvolume centres, support the safe and effective use of ICL in lower myopic ranges, even down to -1.00D. A large-scale multicentre study from Japan demonstrated excellent visual and safety outcomes for patients with low myopia (mean -2.26D), while preserving corneal structure and maintaining optical neutrality.5

Complementing these findings, a prospective study from China comparing the Evo Viva ICL to SMILE in low myopes reported comparable safety and predictability, with superior optical quality measures in the ICL group.6 Additionally, a European study focussing exclusively on patients with myopia less than -3.50D found that Evo Viva ICL implantation provided predictable, stable, and effective outcomes with high efficacy and safety indices.7 These studies broaden the clinical rationale for ICL use, not just in high myopes, but in any myopic patient for whom tissue preservation and long-term flexibility are priorities.

As we continue to witness the global escalation of myopia, particularly in young adults, this strategic flexibility becomes even more relevant. A large-scale French nationwide longitudinal study of more than 630,000 individuals demonstrated that myopia progression continues beyond childhood, with the highest rates of progression observed in teenagers and young adults aged 14 to 29 years.8 This has critical implications for refractive planning. Cataract formation is an inevitability, and patients undergoing vision correction as younger adults will eventually require cataract surgery. With rapid advances in artificial intelligenceassisted IOL optic design now underway,1 it’s vital that we don’t compromise a 25-year-old patient’s visual future by removing excessive tissue today. ICL is already being considered for paediatric myopia in expert hands.9,10

In essence, ICL preserves the full range of future surgical manoeuvrability. There is no permanent compromise to the cornea, and no impact on future intraocular calculations. For this reason, many refractive surgeons now view the ICL as not merely a niche solution, but a thoughtful first-line approach to surgical vision correction in younger myopes.

This shift in thinking is now being formalised. I have been fortunate to contribute, as a co-author, to a forthcoming international consensus statement entitled Controversies and consensus on posterior chamber phakic intraocular lens (PC-pIOL) for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism in healthy phakic eyes.11 The aim of this work is to provide updated, evidence-informed guidance for optimal practice in ICL surgery, especially as indications expand and devices become increasingly refined.

In this context, offering an ICL to a young adult should not be seen as a deviation from conventional practice. Rather, it is a futurefacing strategy – one that respects the biology of the young eye and the rapid evolution of optical technology ahead.

PRESBYOPIA AND THE EVO VIVA ICL

Presbyopia adds another layer of complexity to the refractive landscape. While it has long been one of the most challenging conditions to correct surgically, we are seeing more patients than ever actively seeking solutions.

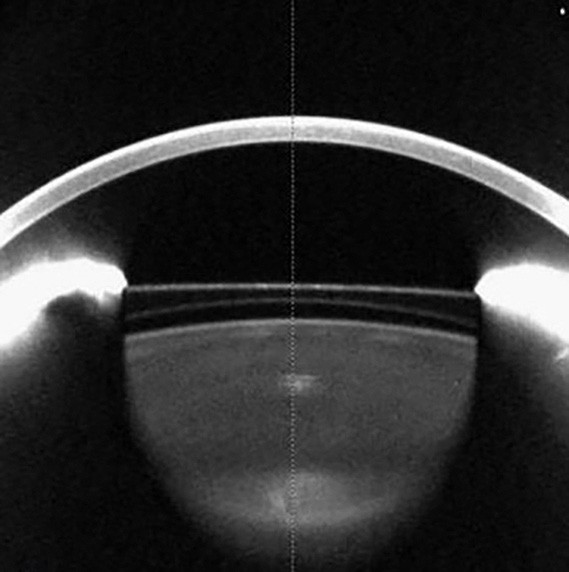

Figures 1A. Optical coherence tomography image of an implanted Evo Viva ICL.

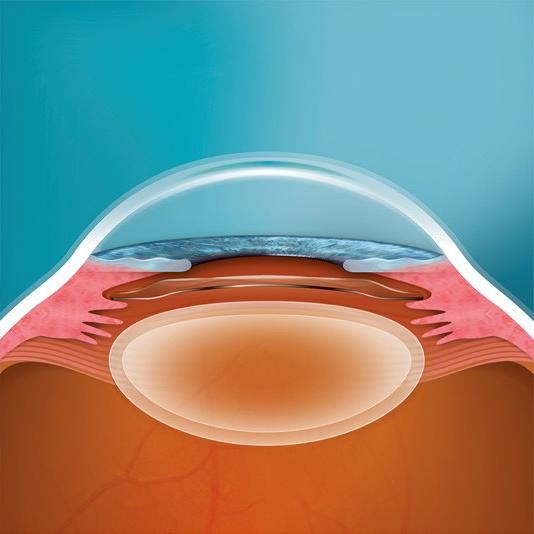

1B. Schematic of same.

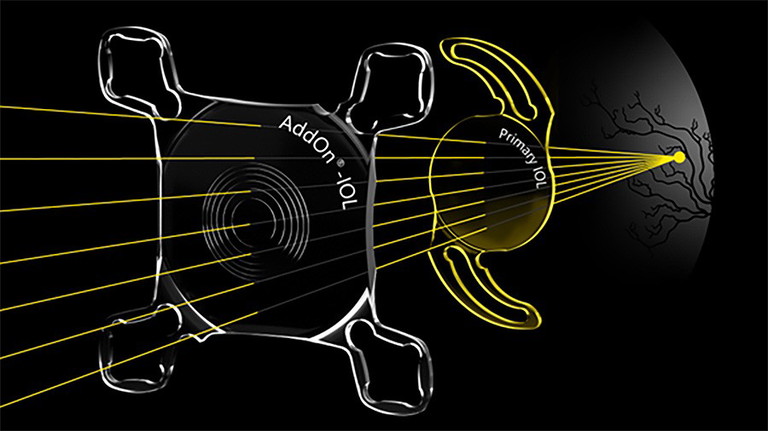

Figure 2. Schematic of primary and AddOn intraocular lens.

Traditionally, the younger presbyope – those in their 40s and 50s – has been one of the hardest groups to treat. Today’s presbyopes are digitally engaged, professionally active, and image conscious. These patients demand surgical options that restore both function and freedom, without compromise.

Traditional laser vision correction offers limited presbyopic solutions, where monovision has been the main strategy. PresbyLASIK laser treatments, such as Presbyond, remain valuable tools in our refractive armamentarium (which we offer at Envision Eye Centre). But they are not suitable for everyone. Presbyond is a LASIK-based form of micromonovision that harnesses controlled spherical aberration to produce an EDOF-type effect to the cornea. It has demonstrated good results in well-selected candidates, especially low myopes and hyperopes with or without astigmatism, as long as they tolerate micromonovision or mild blur in the non-dominant eye.12,13 However, because its success depends significantly on neural adaptability, it has limitations in certain patients, such as those with intolerance to micromonovision, defined in this setting as 1.0 to 1.5D of anisometropia. Additionally, as the altered corneal optics give an EDOF effect and the recommendation is for a monofocal lens later, this strategy may not fully meet the patient’s expectations, and may preclude optimal use of premium IOLs later in life, as these often require a low-aberration corneal profile to perform optimally.

Newer technologies such as Allotex corneal inlays, which implant a human-derived lenticule to restore near vision, also show promise, although they remain investigational in many regions.17

Excitingly, the Evo Viva ICL represents an elegant and strategic solution for myopic presbyopes. The Viva ICL expands upon the standard Evo Viva ICL platform to address presbyopia and was approved for use in Australia in 2023 by the TGA. Additionally, having initially been approved for the correction of presbyopes up to 45 years, this indication was most recently expanded to up to 60 years. As the first surgeon in Australia and New Zealand to implant this lens, I’ve witnessed its ability to restore high-quality, bilateral vision at distance and near in the right patient.

The Evo Viva ICL utilises central and transitional aspheric zones to extend the range of focus while preserving contrast sensitivity, thereby avoiding the trade-offs often associated with diffractive multifocals or corneal monovision. It is specifically for myopic presbyopes, and currently with minimal or no astigmatism. It is worth noting that while the Evo Viva ICL is not suitable for hyperopic presbyopes, or those with significant lenticular changes, it can play a valuable role in the broader strategy of staged refractive care.

“We are no longer operating in an era where refractive surgery is a one-time decision made in isolation”

In a prospective multicentre clinical study, 98.1% of eyes achieved monocular uncorrected near visual acuity (UNVA) of 20/40 or better at six months postimplantation, accompanied by good distance vision. These outcomes were accompanied by high satisfaction and a strong reduction in spectacle dependence.14 Alfonso et al. reported consistent findings, with excellent visual acuity at all distances, preserved contrast sensitivity, and favourable aberrometric profiles.15 Further supporting these results, Packer et al. found the Evo Viva ICL to be effective and safe in presbyopic phakic patients, providing continuous range of vision with minimal photic disturbances, high predictability, and stable refractive outcomes.16

These results position the Evo Viva ICL as a meaningful addition to the refractive toolkit for appropriately selected patients – particularly those seeking visual quality, reversibility, and long-term flexibility. It does not induce dry eye, and unlike laser ablation or lens extraction, it leaves future surgical pathways open. For motivated presbyopic myopes under 55 with stable refractions, Viva ICL offers functional binocular vision at distance and near, without the compromises of more invasive or irreversible modalities.

REFRACTIVE LENS EXCHANGE AND THE EMERGING IOL LANDSCAPE

Refractive lens exchange (RLE) continues to gain traction as presbyopia-correcting IOL technologies improve, particularly among hyperopes over the age of 50 to 55 with early lenticular changes. In these patients, RLE offers predictable refractive outcomes, removes the need for future cataract surgery, and enables spectacle independence when the appropriate IOL is selected. It remains one of the most direct and definitive paths to visual freedom.

However, in younger myopes, RLE should still be approached with caution. Axial elongation increases the risk of retinal complications, particularly in the absence of a complete posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). As highlighted in a recent review, while RLE is gaining popularity, the evidence base, particularly around younger patients, remains limited and nuanced, warranting careful case selection.18

Moreover, as IOL technology continues to evolve, there is a growing sense among refractive surgeons that better solutions may be just around the corner. Removing a clear lens in a patient under 50 years may eliminate the opportunity for them to benefit from future improved IOL technologies, whether these be like today’s MF IOLs, or alternatively, pseudo-accommodating or biomimetic.

Therefore, RLE is a high-stakes decision that must be aligned with long-term planning and realistic expectations.

That said, modern EDOF and MF IOLs have made lens-based options increasingly appealing, reducing the trade-offs between distance and near vision and improving tolerance of visual phenomena compared to earlier-generation MF IOLs. Of particular interest is the secondary supplementary AddOn IOL, which I frequently use to upgrade monofocal outcomes to multifocality (Figure 2). This sulcus-based lens can also be implanted as a dual procedure during primary surgery, combining a monofocal IOL in the capsular bag with a multifocal (toric or non-toric) AddOn IOL in the sulcus. Importantly, this configuration offers reversibility, allowing removal of the multifocal element if patients are intolerant to dysphotopsias. Looking forward, the AddOn IOL platform may eventually incorporate newer presbyopia-correcting technologies as they evolve, potentially bringing us closer to the long-sought goal of reversible, fully customisable refractive lens exchange.

Fortunately, the IOL landscape is advancing rapidly. Non-diffractive EDOF lenses, such as the Medicontur Elon, are emerging as strong contenders in mini-monovision protocols, delivering excellent distance and intermediate vision with functional near acuity, minimal halos, and high satisfaction rates.19-23 EDOF IOLs are especially valuable for patients seeking spectacle independence but unwilling to accept the compromises associated with earlier diffractive designs. They are also better suited than MF IOLs for eyes with prior corneal refractive surgery or subtle macular changes, where contrast preservation is paramount. Future IOL platforms are likely to leverage biometric profiling and customisation, and refined AI-guided optic design to further personalise outcomes.

Ultimately, the decision to proceed with RLE should consider age, ocular health, and lifestyle goals. The key is to operate only when the patient is sufficiently motivated and understands both the benefits and limitations of surgery. As with all refractive decisions, understanding the patient’s expectations and long-term visual priorities is essential.

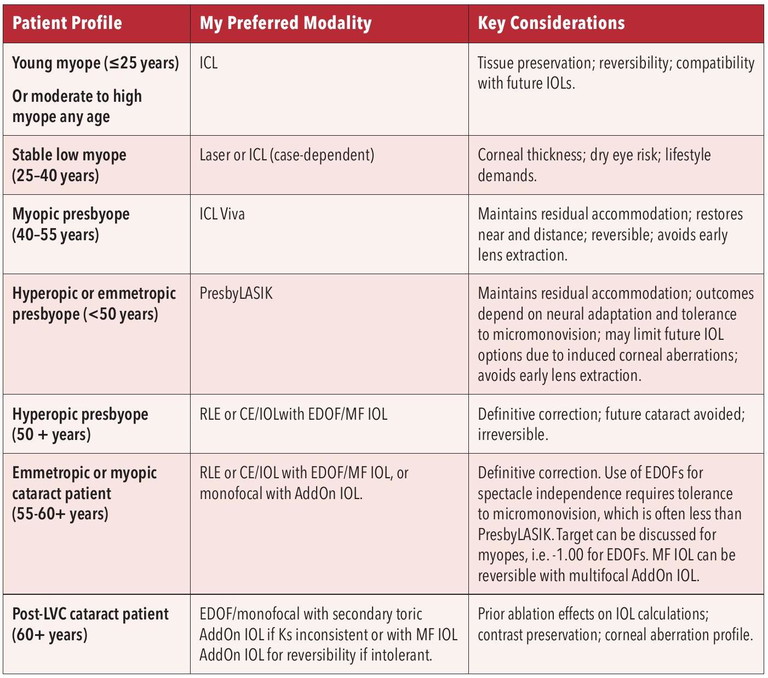

MATCHING THE PATIENT’S LIFE HORIZON

Refractive decision making is no longer a onesize-fits-all approach. As the range of surgical options expands, so too does the need for nuanced patient counselling. Each modality – whether corneal, phakic IOL, or pseudophakic – carries trade-offs in reversibility, adaptability, and future compatibility. It is essential to engage patients in a transparent discussion about their long-term vision goals, occupational and other needs, and the evolving technologies. When refractive surgery is positioned as a journey rather than a single intervention, outcomes become not only more successful, but more sustainable.

The landscape of surgical vision correction is more dynamic than ever. As technology advances, so too must our refractive philosophy. No single modality can, or should, be universally applied. Instead, refractive surgery should follow a layered, lifestage approach: preserving tissue when youth and long visual horizons demand it, and offering definitive lens-based solutions when the patient’s age, anatomy, and lifestyle call for it. To deliver on this paradigm, surgeons must be proficient across all modalities; not simply to expand their toolkit, but to ensure patients are offered the most appropriate strategy rather than being limited by the surgeon’s own scope of practice.

This is not simply about choosing between laser, phakic IOL or lens solutions. It is about sequencing care for each individual patient; matching today’s intervention to tomorrow’s possibilities. For the young adult myope, the ICL is not just a second-line fallback after failed LASIK screening; it is, increasingly, the first-line procedure of choice. Its reversibility, optical neutrality with additive technology, lack of association with dry eye, and compatibility with future technologies elevate it beyond correction into the realm of long-term strategy.

Similarly, the ICL Viva is emerging as a strategic solution in the presbyopic space, offering functional near and distance vision while preserving the natural lens and ocular surface. This allows us to defer lens extraction without compromising spectacle independence. When the time for lens-based surgery arrives, modern EDOF and next-generation MF IOLs allow us to further personalise outcomes. This phakicto-pseudophakic progression may well become the new standard, as we move away from ‘one-and-done’ procedures toward adaptive, life phase-appropriate refractive strategies.

What ties all of this together is the principle of foresight. We are no longer operating in an era where refractive surgery is a one-time decision made in isolation. Patients are living longer, working later, and expecting more from their vision across decades of life. Our surgical planning must reflect that. The question is not just “Can I correct this refractive error today?” but rather, “What will this eye need in 10, 20, or 30+ years – and how can I protect those future choices?”

That guiding philosophy underpins this article and informs my practice: refractive care that is personal, strategic, and futurefocussed. From corneal laser to phakic IOLs, from PresbyLASIK to ICL Viva, and ultimately to intelligent lens exchange, the journey to pure sight is no longer a single procedure, it is a continuum. And as surgeons, we must be fluent in every step of that spectrum.

To earn your CPD hours from this article visit mieducation.com/surgical-vision-correction-fromlaser-to-lenses.

Alison LS Chiu FRANZCO FWCRSVS PhD MBBS (Hons) BMedSc (Hons I)Grad Dip Refractive Surgery is the Medical Director of Pure Sight Eye Surgeons in Paddington and Richmond, NSW, and additionally consults at Envision Eye Centre and laser suite in Macquarie Street, Sydney. She is fellowship-trained in laser vision correction and lens based refractive surgery. Her expertise includes all forms of laser surgery, routine and complex cataract surgery, refractive lens exchange surgery, and implantable collamer lens (ICL) surgery. She is regularly invited to lecture and teach internationally, provide expert opinion, and contribute to research and development.

The author has no financial interest.

References available at mieducation.com.

Table 1. Refractive strategy by life stage: key considerations.